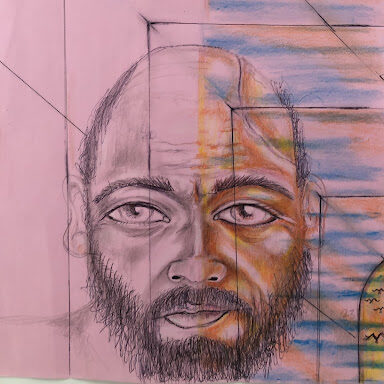

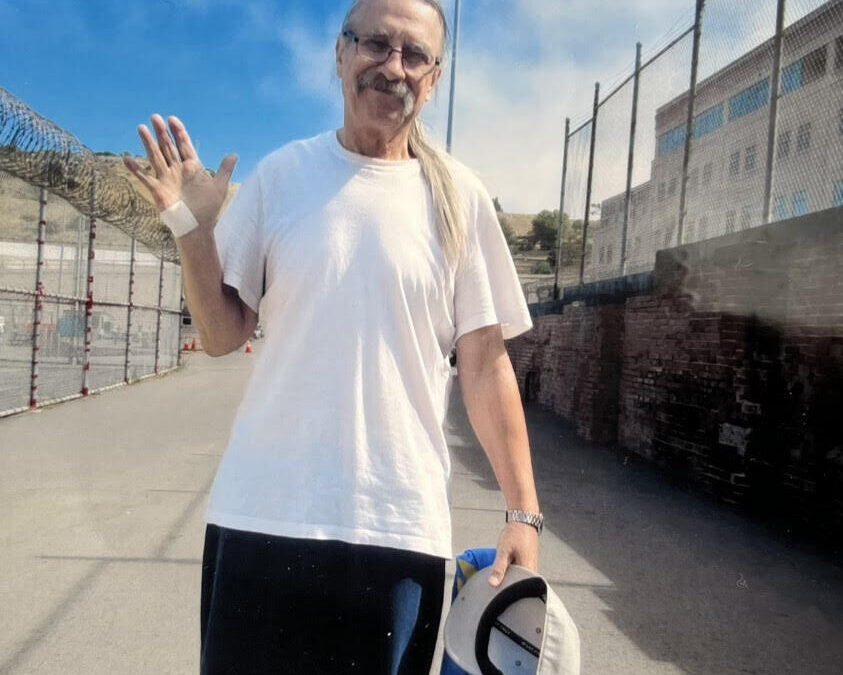

Alex, 56

A Running Lion

Unintended Consequences

Alex, 56

Incarcerated: 28 years

Housed: San Quentin State Prison, San Quentin, CA

Who would ever have thought that the day would come when a lion would run from a deer? I feel like that day has truly come for me.

I was raised in a neighborhood where we were taught that fighting is how problems were solved. I was involved in so many fights throughout my life that it became my go-to coping mechanism. If an argument felt as if it were getting too tense or heated, I would take the first swing. For me, arguing caused doubt. I would cut to the chase. I now realize how wrong I was. Upon finally realizing my entire way of thinking was totally messed up, I am learning new coping mechanisms, and in doing so, I have become the lion running from the deer. I’m not writing this to glorify violence or to seek pity. I am writing to reflect on the situations which were meant for good but turned into bad outcomes. Unintended consequences became the dark cloud in my life that shaped my frame of thought and led me down a road bound for nowhere.

I grew up between Compton and Los Angeles. My mother and father broke up in 1974 when I was seven. I remember wondering why. My father left LA and headed off to the Bay Area where he took over Uncle Bob’s Auto Shop. Before he left, he moved us into a newly built apartment complex called ‘Ujema Village’. It was surrounded by a big field, and felt safe. My mom, brother, six sisters, and I were one of the first families to move in, like a pack of lions on this new ground we called ‘The Village’. As kids, we ran around like newborn lion cubs fresh out the den. For me, this place was like a giant playground. We rode our bikes, played hide and seek, dodgeball, boxed, wrestled and even had dirt rock fights in the empty fields. As more and more people moved in, the pecking orders began to form and fights drew the conclusion. If a dispute got out of hand, our parents would make us go to the back yard, fight it out, and then shake hands which meant it was done and over with. Every now and then, there would even be a family versus family fight. At the end of the day, we were all friends.

After a year of bonding with my new friends, my life took a sudden turn. The mother of my best friend, Darryl Anderson, and my mother became good friends. Darryl’s mother convinced my mother to join a church called Emmanuel Temple. My mother meant well. She had reached the point in her life where she was ready to change her way of living. She stopped drinking, smoking and going to parties. The church for me was the beginning of a very hard, depressed and confused life.

After my mother joined the church, every one of the church rules became the law in our house. Everyone but my big brother had to follow them. I had a big boy’s Market toy truck that I kept my hot wheels and toy men in. I would pretend my toy men were the different people who had picked on me. I would pretend that I was those older guys and created my own scenario in my mind where I got my revenge.

When the Andersons moved out of the village, I no longer had his help whenever I got into a fight. My brother wouldn’t help whenever I got into a pickle, nor did he allow me to run around with him. It was as if he was ashamed of me for being square. I felt betrayed before I knew what the word meant. I was so isolated that all I could really do was observe people and their different personalities. Then came the seventh grade.

Seventh grade became the straw that broke the camel’s back. My first day of Junior High school, I was laughed at. First came the look, then the whisper, on to the giggles and snickers. When I went up north to the Bay Area to visit my dad over summer vacation, he bought my school clothes. I was happy and thought I was looking good. No! Apparently, the dress code varied from city to city. So, I was a poor reader, could not spell, and my dress code was not up to par either. I couldn’t catch a break. In addition to being teased in the neighborhood, I was also teased at school. People I never knew, people I thought I knew, and girls that mesmerized me, all laughed at me for nearly half of my seventh grade year. I was becoming overwhelmed with frustration and anger. I got into fight after fight. My twin sister had $200 that she saved up from a summer job, and she bought me some more clothes. She really took a load off of me, but the damage was already done.

As I struggled to fit in with my peers, my mother was struggling to change me into a Christian. She whipped me regularly. I got my ass beat for getting in trouble at school; however, the only way to get people to leave me alone was to fight. As the church would say, “spare the rod, hate the child”. The strangest part of it all is, although I had become an outcast in my neighborhood, once I started to fight a lot, somehow I became a part of the neighborhood again. Back then, if anyone lost a fight, the loser was teased. If a person refused to fight, they would be picked on until you fought. But, if you won a fight, particularly outside of the neighborhood, that win was credited towards the neighborhood’s winning record. I was already the poster child for other people’s laughter. I could not afford to be talked about anymore, nor could I continue to put up with it. Winning wasn’t an option, it was a necessity.

I would say that halfway through the seventh grade the teasing at the school had stopped. The fighting paid off a little, but it kept me in trouble with the school and my mother. This situation repeatedly caused me to stay in a defensive state of mind. I was trapped by the repeating situation.

Because I was either stuck in the house with my sisters or at church, I did not get involved in common things such as sports. I was not any good at basketball, baseball, or football, nor did I watch it on TV. Whenever I did attempt to get involved in sports, I was either no good at it or I did not know the rules. Therefore, the teasing became non-stop. After a while, I just began to avoid sports and reading at all cost, and anything else that made people talk about me in my mind. Those two things only opened up the door for people to clown me and put me down. After a while, I preferred staying in the house and out of the way.

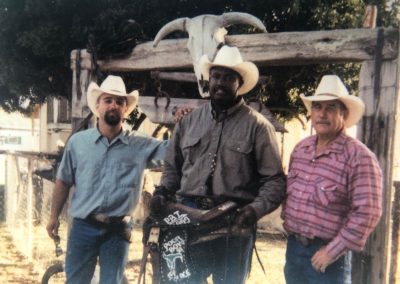

Godfather was one of the older people that I looked up to. He was also the leader of the village at that time. Godfather would have us all in field boxing and wrestling with each other. He made sure things were fair and he matched us up by size or skill. He was always there for me. V-Dog was another one of the OG’s who was there for me. I did not like him at first, because he used to make me fight Curtis when we were younger. High school was the changing point in my life. I was officially a gang member. I could not believe the respect I was getting and I was not used to it. The people whose respect I used to seek now looked up to me. I even drew the attention of Snake, who was the new leader of ‘The Village’. Snake was one of the most feared and respected people in the neighborhood. Snake was the type of person you did not want to piss off, and he held the knockout record everywhere he went. Snake took over the neighborhood from Godfather and took the knockout record from V-Dog when they had a fight over my sister Tracy. Snake saw something in me that only three other people had seen in me. Darryl Anderson, Godfather and V-Dog were my best friends. These three people kept my head above water, but it was Snake who took me completely out of the water and under his wing.

My first encounter with the law was when I was about 15 years old. I wanted to impress V-Dog by taking a members-only jacket from a person. My second encounter with the law was when I ended up shooting a guy in a fight. Big Darryl, who was engaged to my sister Ramona, was huge; the biggest dude I ever saw in my life. His younger brother, Tone, and I were friends and we used to race each other in our cars. Tone had a Vega; I had a ‘63 Volkswagen that my father gave me. A couple people robbed Tone and it so happened that they moved into the Village. Big Darryl wanted to deal with them but he did not want to offend my sister Ramona, so I told him I would handle it. Long story short, things got out of hand and I ended up shooting one of the guys and nearly starting a war.

I ended up in a fight with one of the guys. They pulled up and jumped out of the car. My brother was out there. In fact, that was the first time he ever helped me. My friend had a gun. I told him, “Give me the gun and go get the homies. My brother said, “you and him are about to get down,” meaning I was about to fight. I tried to hand it off to my sister-in-law but the fight broke out too fast. I was standing over the guy who I fought and his friends were running toward me to get me off of him. It was then that I turned around and fired the gun hitting one of them in the arm. I went to Juvenile Hall for 10 days. The guy that I shot told the court that he had no business fighting me and they let me go on probation.

When I first came to prison for this crime, I was mad at everybody but myself. I figured I would die in prison, so I just did not care. I caught a couple of batteries on inmates. I was in a few riots. I was making wine. We used to sit in the hole and compare our 115’s to see who did the most in the riot. That was where my thoughts were. I didn’t want any friends, just associates.

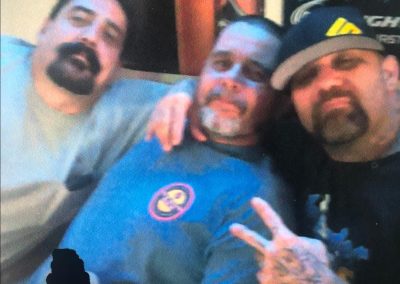

One particular guy, Kasper, broke the ice. We were opposite but the same. It felt good to laugh again. Before I met Kasper, I was on the B-yard. But after a big riot, when I got out the hole, they sent me to the A-yard. I went to the hole 3 times in that yard. One of the things that I thank God for. I now have my friends who are the four Ds and a K. All five of my friends are on the streets doing well and rooting for me to get out. I thank God because now I know I will be able to surround myself with positive people.

Now you know some of my path–let’s get back to the lion running from a deer. After coming to San Quentin, truthfully, I was so happy to know I didn’t have to make any weapons. I didn’t have to stand in one area while on the yard and I could talk to other races without finding out they got in trouble for it with their tribe. But what I did not know was that my real test had begun. One thing for sure was that we were all equal in prison, so I’m not trying to downplay any other person as if I am better. I ran into people that tried all my triggers so many times that I wanted to react. I kept telling myself, if other people can do it, then I can too. Those people and my triggers are what my new self is running from. I try to stay to myself. It is a struggle, but I got myself here and I plan on getting to the finish line.

If I could say anything to my younger self, I would say, “Don’t be scared to speak up. Tell your mother about the teasing and bullying. Tell her about the problems at school.” I would also tell myself, “Tell your father you want to move in with him to learn the male perspective of life.” I would tell myself not to search for love, but to allow love to come to me. Searching for love will not change the pain in my life. I would tell myself, “Do not turn to drugs when you are down. Things will only get worse.” Growing up in a house full of women, I was told girls are “sugar, spice, and everything nice” and boys are “snakes and snails and puppy dog tails”. I was told men don’t cry and men don’t tell. Even my household chores were called “man jobs.” I took out the trash, swept the staircase, and cleaned the bathroom. I never had to wash clothes, cook, or do the dishes. I don’t even recall being hugged by my father, not even after getting off the airplane for my summer vacation. No hugs that I could recall, and as a result of this, I became a hugger when I was in a relationship. I now realize that I lacked compassion for others because compassion was not something I saw growing up.

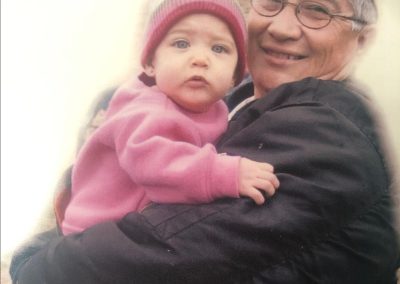

The happiest moment that I could recall is when my uncle Gilbert and my father would take all the kids to the beach. They both had vans, but my uncle was tall, and my father was short and buff. I was a kid full of imagination, so they were caricatures for me to mimic when I played around with my toys. Years later, as I sat on the couch watching my kids play, I had the title Dad and Uncle. I was the person they would remember as their protector.