It was the summer of 1962 and my first year of clinical training for seminary. I was 23. I heard San Quentin was accepting people for training ministers and priests for a 12-week program.

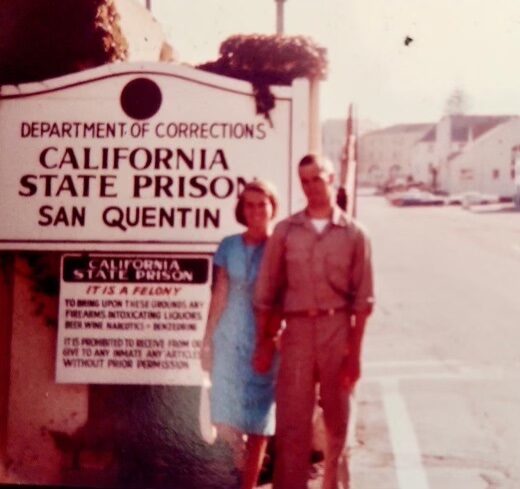

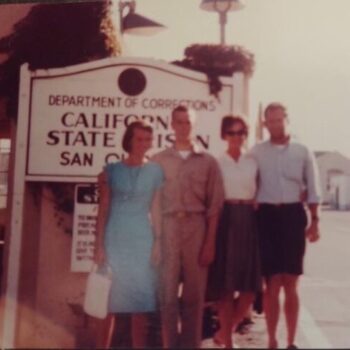

Summer Chaplain 1962

San Quentin State Prison: 3 months

Diane: Tell us how you started working inside San Quentin.

Alex: It was the summer of 1962 and my first year of clinical training for seminary. I was 23. I heard San Quentin was accepting people for training ministers and priests for a 12-week program.

Diane: Share your first days on the job.

Alex: My first week I started as a guard, not as a chaplain or as a priest. The warden was being strong-armed into having us there and he made that very clear. He didn’t want the disruption. With extreme exuberance, he shared that if we were taken as a hostage they wouldn’t trade anything for us.The first week four of us from seminary, worked as guards the four to midnight, the graveyard shift as guards. The first morning he has us in uniform standing before his desk, “OK, you ‘Christ-screamers,’ look at these!” Whereupon, he yanked open his desk drawer and took out five eight by ten, black and white pictures of guards lying dead on the floor, in pools of their own blood. He said something like “It’s nasty out there, don’t forget it. Don’t befriend anyone, this is a school of crime. This is where people come to get it right – the next time around.” He was very negative.

Diane: Holy hell, talk about trauma.

Alex: After the first week, as chaplins we would meet every day. The prisoners could come in and talk with us and get stuff off their chest. Together, we would try to recreate the conversations and go over them. Our mentors would tell us what we should have said or what we should have not said. For me, it was time to hear the humans of San Quentin. They are human and not monsters.

Diane: Did one human in particular stand out?

Alex:There was one that stood out to me, an Indian Boy that was burned and tortured as a child. He didn’t have a chance in this world other than to become violent, it was all that he knew. Oh, I had a Dr. Bernard Finch as my patient. He and his secretary decided to kill his wife, he was tired of her and they followed through. He was such a swell guy, you would have never known. They both received seven years to life. He was released and went back into practicing medicine.

Diane: Tell us about a typical day.

Alex: First, we would walk the yard and strike up conversations and were permitted to wear our regular clothes. Not everyone would talk to us. The ones that would share we would extend an invitation and set up a meeting. We would collect stories like the kind that Humans of San Quentin are collecting now. We couldn’t publicize their stories. That’s why it is so great that you are sharing their stories. It makes such a difference!

Diane: What was your most memorable experience?

Alex: The day I watched a double execution. It was for two Hispanic kids, they were hired to kill the daughter-in-law of an elderly lady. She was afraid her son would move out with his new wife. Elizabeth Duncan, was her name, she had her daughter-in-law beaten and buried alive, sad stuff.

Diane: Walk us through that experience.

Alex: The execution room had chairs and a wheel that sealed the gas chamber. There was a small grandstand that looked like it was from a small high school. It held about 30 people. We waited outside. We decided to represent the other side. We were the only ones there for them except for their brother. The rest of the people were citizens and there to make sure justice was carried out. We were ushered into the grandstands while they brought the brothers in. The one brother looked at his brother and put his thumb up. It was beautiful. They brought in the old lady next. She had no teeth and you just can’t understand that it’s real. We had no emotion, it was hard to process. Later that night when we were hanging out it hit us and we wept. That made us great advocates against the death penalty. Her name was Elizabeth Ann Duncan and she was the last lady executed in the state of California.

A close friend of mine has identified that so many prisoners that were executed were affected by fetal alcohol syndrome. The writing was on the wall before they were even born. It was victims making others victims. It’s crazy to think about. It was a rough summer for me and one of the reasons I went back to school.

Diane: You mentioned seeing a woman being executed, were women housed in San Quentin?

Alex: They brought her in from the women’s prison. All state executions were brought to San Quentin. She was the one that hired the Hispanic boys to kill her daughter-in-law. There were no women housed at San Quentin during my time.

Diane: Were there any classes or education in San Quentin?

Alex: As I recall there were classes of some sort. It seemed to me that it was underfunded and they weren’t rehabilitated. The name of the California prison system, California Department of Corrections made me laugh (in a sad way) because there was not much correction going on. People were in there for not only selling heroin but doing heroin. They were not even dealers! That makes no sense to me! There were all sorts of interesting people that were not much more criminal than I am. It seemed so wrong!

Diane: Were the people incarcerated given work?

Alex: Inside there was a furniture factory and glue sniffing was a problem. The inmates were paid pennies per hour. Cigarettes were coined for buying anything. The state dispersed tobacco and papers to roll their own smokes.

Diane: Do you remember any of the conversations you had with prisoners?

Alex: Some people would be self-justifying- saying they got a bad deal. There was complaining and victimization. Many were victims – that is for sure, if you hang on to that, you don’t come around. The ones that would come around would say – I was victimized but now I know right from wrong. They would say they are sorry for what they did. Those are the ones that grew and changed.

Diane: In our experience, there is not a man or a woman that has come to us that wasn’t a victim first.

Alex: There wouldn’t be. I started out as a priest and I did that for six years. Then I really came to the conclusion that the people I met couldn’t hear what I was trying to preach or say. I decided to take a pause and for ten years retooled myself as a psychoanalyst. I practiced for 36 years and taught at the University of Jefferson in Philadelphia. In my work, while trying to heal and overcome old wounds was exceedingly difficult and took so much time and patience. We couldn’t even speak into people’s lives for such a long time. Trust took time. It’s like the joke: how many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One but the light bulb has to want to change.

Diane: Did your experience at San Quentin change your career path?

Alex: One of the things that changed me was the one time I was at the pulpit once in 1969, and it was the beginning of the civil rights movement. My congregation was right-wing and seemed prejudiced. One time I was at the pulpit, I said to myself I almost hate you people. Then I thought wow, I need to deal with my own demons. So it became how do you help people change and actually hear me? The first five years of being an analyst you work on your own stuff then you can move into helping others. It’s very difficult to help people. You have to wait a long time to be able to say anything. But, the work that you do Diane reaches so many more people. You have a real chance to affect people in a good way and to actually be heard. People that read your stores can actually connect and understand.

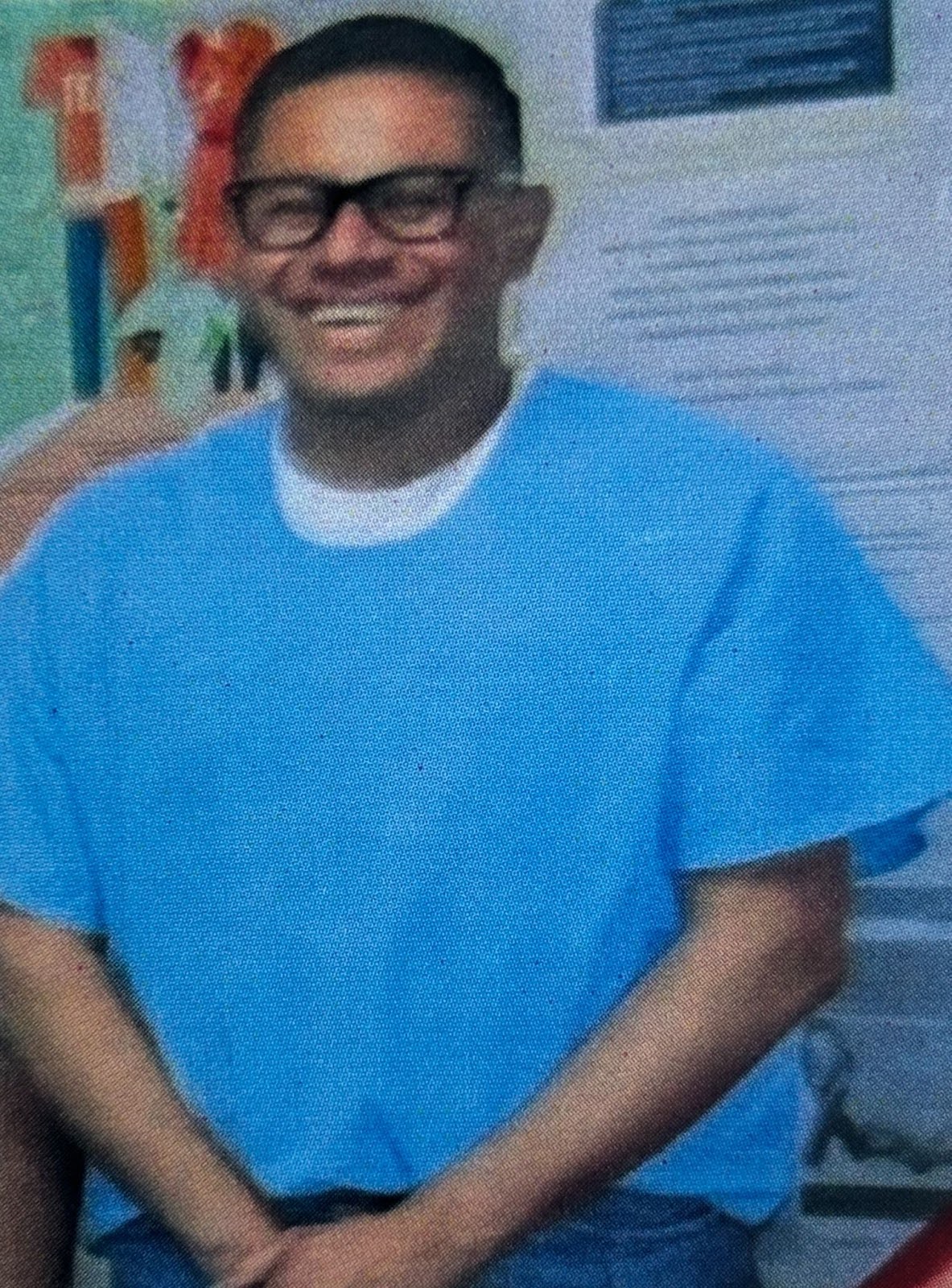

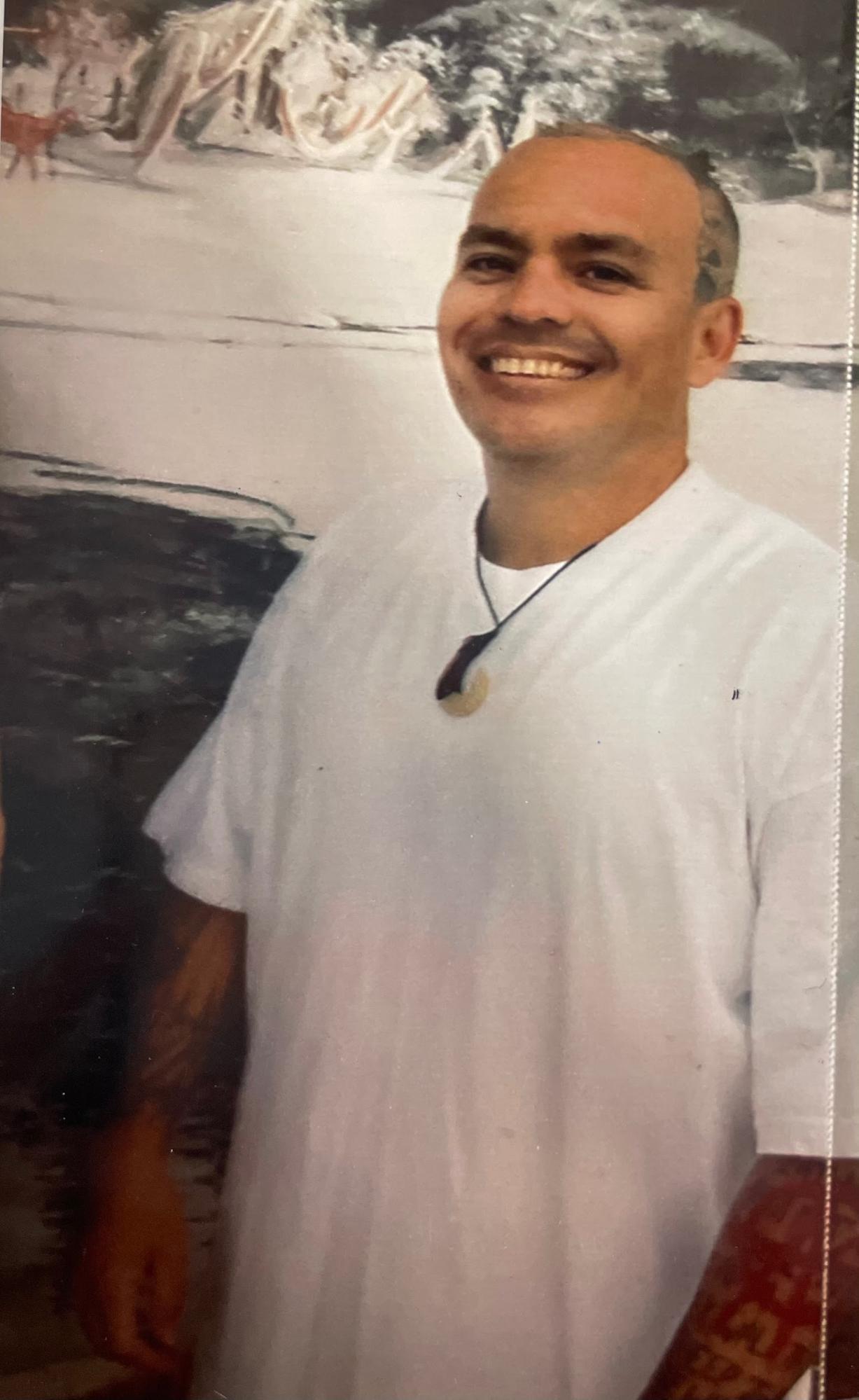

Diane: The gravity of your recognition for our work is humbling. We are doing our best to educate the “free people.” In order to reach the masses, people need to be able to connect. We strive to feature as many people and their stories as humanly possible. Simply hearing about another person’s daily life can potentially connect you to them. We hope they are connections for the better. We eagerly want to visit more prisons to connect people.

Alex: Have you received any funding?

Diane: Just friends so far. We are in the midst of hiring someone to help with development. I need to go out and ask for money, but it’s a skill I need to learn. I need to come out of my comfort zone and ask for all of the people who want to be featured living behind bars. I am passionate about equal rights. It is difficult for me to sit back as so many people are intentionally silenced. With more funds, we can enhance our mission of hiring more people who have been incarcerated. Employing one person previously incarcerated can change the lives and opportunities of many. The value people previously incarcerated bring to our business is valuable. I turn to them all day long and draw off from their lived experience.

Alex: Have you ever heard of the book Death Row Chaplain?

It’s a book about a priest, Earl Smith, who worked on death row. He was a former criminal turned chaplain. Smith played chess with Charles Manson, negotiated truces between rival gangs, and bore witness to the final thoughts of many death row inmates. It’s an interesting book!

Diane: How were the politics inside structured back then?

Alex: It was power. They would work out, and there was a ton of violence. An escape attempt happened while I was there. They captured a guard and pistol-whipped him. The guards were afraid and the prisoners were afraid which caused more violence – as you can imagine.

Diane: Was there one instance that kept you up at night?

Alex: Yes, that little Indian kid I talked about being tortured and scalded by hot water. I felt special that he would even share with me. I will never forget him.

Diane: Did you bond with one prisoner in particular?

Alex: No, we bonded with the other chaplains. One of the chaplains I worked with had a nervous breakdown from the stress and fell off. We lost contact with him. Like I said, it was a tough summer!

Diane: Thank you Alex for sharing your time at San Quentin. Your story is impactful and we are honored to publish it.

Alex: My pleasure.