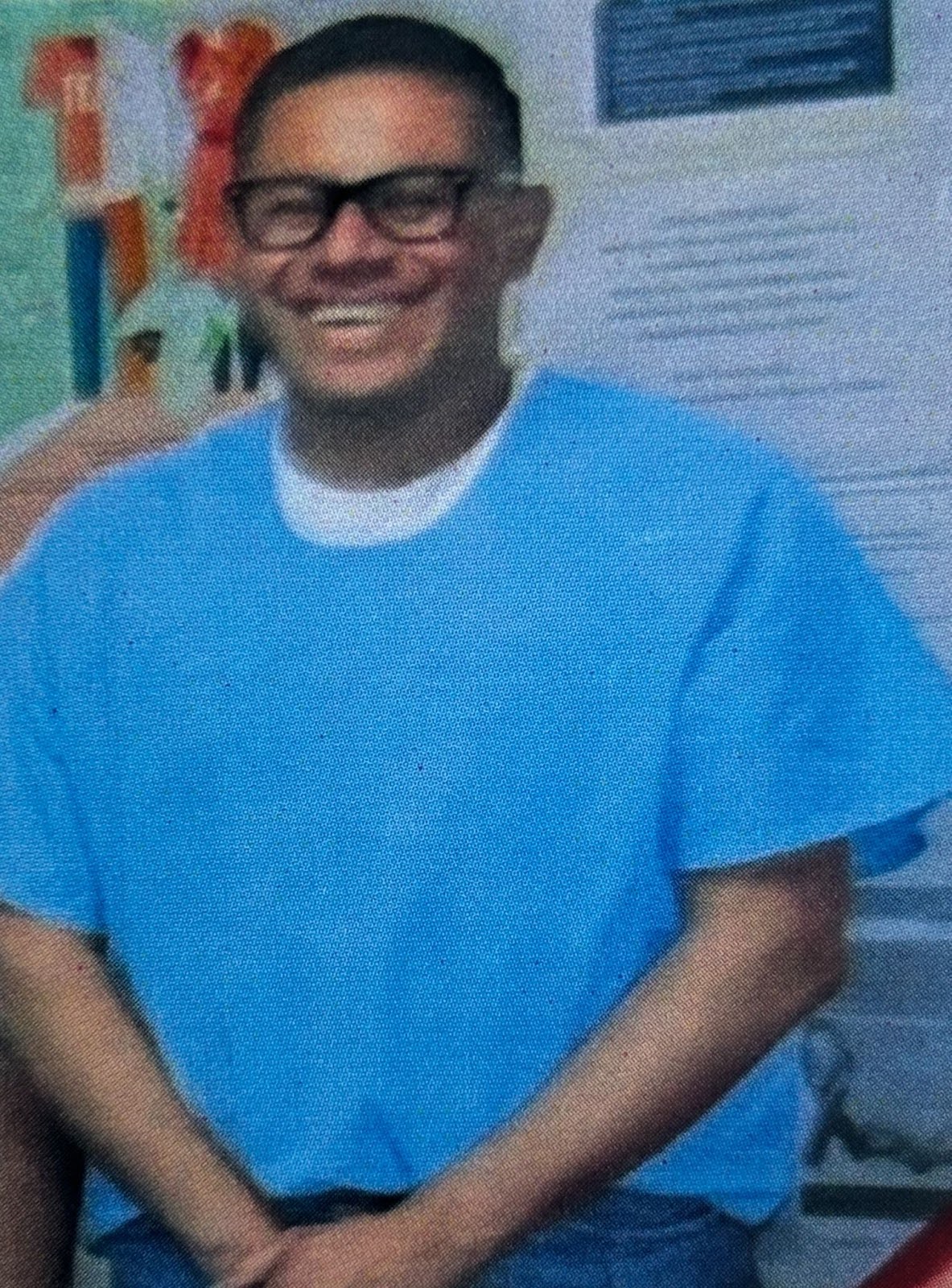

As I sat before two people who would determine whether I was suitable for parole, I was reminded of the jury of twelve that sentenced me to 102 years to life for the murder of another human being, exactly twenty years ago. I was sixteen years old then. I have since received a commutation from Governor Jerry Brown that reduced my sentence from 102 years to life, to 19 years to life.

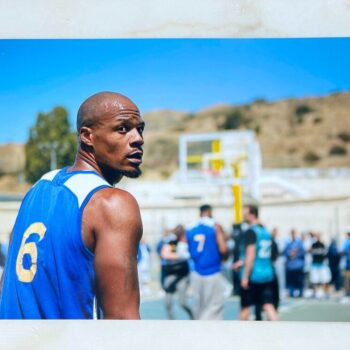

Before I tell you about the Board’s most recent decision on Dec 17, 2020, I need to back up and share with you my first experience at my initial board hearing. At 33, I was very hyper during that hearing and I received a three year denial. This meant I would not have another suitability hearing until three years later. I was told to stay clean from write-ups during this three year period and I did not. On July 27, 2020, I used a pay phone to call my mother without permission. Here is my justification on why I called her, I was at work all day, 14 hours straight, cleaning 10 cells where people had tested positive for Covid-19. Secondly, no San Quentin staff clean cells, it’s up to the inmates. I am part of a voluntary team who chooses to give back to the men in blue, to our community; if we don’t clean, no one will. Lastly, after a long day of stressful work, I wanted to use the phone to hear the comfort that comes from hearing a mother’s voice.

Stress, anxiety, depression and hope were all with me, when I went before the Board this second time. At 10:30 am, I nervously sat at a computer in the hearing room. I had not slept in two nights. Thoughts were racing through my mind about the write-up I received six months earlier for calling my mom on the pay phone without permission. The first question they asked was, “Do you know why you were denied the first time you went before the board?” I answered, “Yes, because I engaged in criminal thinking in 2015.” I felt entitled and impulsive, when caught using a cellphone. They wanted to know why I again used a phone without permission. I owned it and did not try to hide the truth. Both commissioners asked question after question after question about the second write-up, beating me up with their words.

“Do you know how different this hearing would have been had you not had a write-up?” They asked. “Yes” I said. These two officials had so much power over me, I felt like I was failing and not representing myself. I wanted to point out that although I did get on the phone without permission, I was no longer a criminal. Before, I didn’t give a damn about rules and regulations. But today I do. For me to be a criminal nowadays is something that is disrespectful towards humanity, and today I appreciate humanity. I am not a criminal.

At this subsequent hearing, the commissioner told me it’s his job to make sure that my getting on the phone was not indicative of a pattern of criminal behavior. The questions felt so hard, maybe because I knew I screwed up by getting written-up. They asked about my crime and why I did it. I told them I wanted to be tough so I’d get praise from my peers in order to feel validated. And then he switched back to questioning me about the write-up, the phone call to my mom.

I stood my ground, trying to show him who I was then, and who I am now. I felt intimidated. Small.

My intern did a great closing and I ended by saying I wanted to honor my victims. The commissioners went into deliberation for about ten to fifteen minutes. I talked to my attorney and thought I might get a split decision. But I trusted God. As much as I screwed up, I had to trust God.

When the commissioners returned, one said he didn’t agree with my attorney that the phone write-up was not a connection to my crime. He said that, by getting on the phone, it was a direct connection to the murder I committed at sixteen. I put my head down.

Then he said, however, based on the support letters I received from staff showing maturity, he saw my growth and believed the phone was just a bad decision. He also mentioned the fact that my honesty and acceptance of the facts was very important. Next, he said they had found me suitable for parole, that I did not pose an unreasonable risk to society. Everything else was a blur. I mean, wow! Two years ago I had 102 years to life. And now I might be going home. Who would have thought? But then there is my faith in God: that miracles can and do happen. When all else seemed impossible, my prayer was answered with the stroke of a whispered “Trust in God.” In that last-gasp moment of hope a sentence that began with 102 years to life just vanished into thin air.