I was basically flung out of San Quentin by the seat of my pants. I truly wasn’t ready. Yes, I had my exit strategy and parole plans set for the board, but I wasn’t given the time to set up housing or put my plans into action before I was released. I thought I had a little bit of breathing room – as in, I thought I had a few more months in prison. Two weeks wasn’t enough time for me to fully process leaving behind the routines I had become accustomed to over the course of fifteen years behind bars. I am autistic and have struggled with transitions from the start. Frankly, the thought of leaving prison so soon was horrifying.

Shortly after my arrest, in Shasta County Jail at the age of 23, my attorney wanted me to be tested for Asperger’s, a Developmental Disability of which I’d never heard of. Upon his request, I agreed. The attorney hired the psychologist who tested me. When the test came back negative, I believed I didn’t have Aspergers. However, I now understand that, had the “negative” report been read back to me in a way that was clear and informative, I would have learned that I did indeed have this Condition. Having zero knowledge of psychological jargon, I didn’t learn of my autism until several years later. That being said, I always knew I was different; I didn’t seem like everyone else. I always felt uncomfortable, even in my own skin, even if only slightly; something in me was always off. One of the hindering differences with people on the autism spectrum, is we trust everyone, especially people with authority. We see the world as black or white and take everything at face value. That’s why I believed my Attorney when he said “Well Joe, you don’t got it [Asperger’s].” I let this idea of having Asperger’s go. Discarded it, since my attorney and according to the Psych report [which I didn’t read at the time because I trusted my attorney] stated that I didn’t have this condition.

It wasn’t until 2009, a year after I arrived at my first mainline prison in Susanville, California, that I was having one of my weekly phone calls with my mom. She sounded serious. But the kind of serious you become when something exciting has happened. She told me “I went to the salon with my girlfriend to get my hair done; she had brought her son with her that day. Joe, he looked just like you, acted just like you, talked just like you and even had his hair the same way. When I told him this, my girlfriend said ‘God I hope not, my son has Autism!’”

I was stunned, I had no words. My thoughts were ….that piece of shit lawyer lied to me…. My mom sent me two books on autism and I contacted my former attorney and asked for a copy of the original test report. I read the books as a pessimist since the report said I didn’t have Asperger’s. Those two books, The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome – by: Dr. Tony Attwood, and Asperger’s from the inside out – by Michael John Carley, spelled out my entire damn life.

I then received the psych report in the mail. As I shared before, I didn’t understand psychological lingo at all back then; so terms used in the report as Rule out to me meant that those possibilities had been discarded. I then came to learn that in psychological terms ‘Rule Out’ means, what has been ‘Ruled Out’ is the determined diagnosis. I didn’t know that at the time; so the diagnosis page stated: Rule out: Asperger’s syndrome; Rule out: Social anxiety disorder; Rule out: Depression Disorder NOS;And so on and so forth.

Since these were ‘Ruled out’ I just felt confused between the books and the report, until I came to the end of the report where there was a synopsis of the tests and diagnosis. The Psychologist stated: Mr. Krauter has clear indicators for developmental issues such as Non-Verbal Learning Disorder, also called PDD/NOS, also called ASPERGER’S SYNDROME.

This lit a fire in me to seek testing and diagnosis. My diagnosis could have been entered as new evidence getting me back into court for a hopeful resentencing and lesser sentence. But as time went by I made peace with my crime and chose to do the time, earn the right to get out and seek wellness as I pursued my testing and diagnosis.

It was the middle of 2009. I had a mission, a purpose. I immediately filled out a request to seek help from the mental health program. I took my books and psych report. After I told the clinician what I wanted, he said to my face “You don’t have Asperger’s, I can tell you don’t have it”. He didn’t care what my books or report said and continued with “beat it”, I wasn’t his concern according to their manual of protocols.

The same response happened at every prison I transferred to seeking testing and diagnosis, including San Quentin: We Don’t Test For That. SQ did however offer a broad spectrum diagnostic test. I was asked if I wanted to take that test. At this point I was so depressed and going down in emotional flames that I just shrugged and said ‘sure, why not’. This introduced me to my very first Clinician: Lizelle Cline. Ms. Cline saw how wrecked I was mentally and emotionally. She knew immediately that I needed help and was actually compassionate and wanted to help me. She asked me what I wanted and I told her I wanted testing for Asperger’s syndrome. Ms. Cline told me that wasn’t offered here at SQ normally. But she saw my depression and said “I want you to hold on for two weeks, and I’ll see you again. Can you do that for me?” I nodded yes and we finished our session for that day. Ten days later I was called in to see Ms. Cline. She informed me that she requested that I be tested for Asperger’s Syndrome and PDD/NOS, and that her request had been granted. Officially, on April of 2015 I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome on the Autism Spectrum Disorder.

During incarceration I received five years of intensive weekly treatment. My counseling experiences inside were acceptable but piecemeal and disorganized. Only two of my clinicians specialized in Autism; One was my Psychiatrist, Dr. Lona, but was only there for three months. The other was an Intern Clinician, Dr. Anjalee Greenwood, who specialized in treating people on the autism spectrum. In a nutshell, I did not receive the proper Autism therapies I should have as a newly diagnosed person on the Autism spectrum; the prison mental health system doesn’t have ANY protocols in place for treating autistics while inside. All the other treatments I required besides what was offered at SQ I had to research and provide myself as best as I could with the limited ability and accessibilities I had.

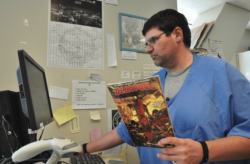

Although it was unknown to me at the time, the prison gave me a safe space and social treatment tools by hiring me in the SQ library. My abilities to hyper-focus, organizational skills, powerful memory and drive for efficiency along with my affinity for technology and desire to help people let me help turn SQ’s library from a small rinky dink prison library into a strong hub of information, recreation and legal work. My pattern recognition along with my desire for efficiency let me and the other workers clean out all the exhausted reading materials and replace them with up to date desired reading material.

Autistics crave routine. For me, it is because the world around me is so chaotic due to sensory overload. Routines allow me to focus on what I’m doing and where I’m going so that I don’t get completely bombarded by the world around me without mercy. To have a routine is to be soothed. Comforted with the knowledge that I can have control and safely be controlled in a set series of actions and reactions. Even though prison is “structured” with rules, regulations and routine, the guards, free staff and inmates create their own chaos within the routines causing disruptions and distress which is very difficult to navigate or overcome; especially since most of the chaos is senseless and carries no logic.

During incarceration I had three major fears, never going home, hurting someone and becoming a monster. Allowing my pattern of who I am mutated by the prison system’s patterns of ugliness, rage, desperation, despair and violence to warp me into a monstrous version of myself.

The most serious meltdown I ever had in prison was because of SQ’s optometry. The majority of my sensory overload is connected to my eyes and ears. I need specially made glasses to protect my eyes, I suffer from serious light sensitivity. My sight is connected with my ears, when lights get brighter my hearing sharpens and things get louder for me. I mitigate this with transitional lenses that are anti-scratch, polarized to prevent glare, grinded a specific way so that the edge of the lenses don’t refract light and are wide enough to catch my dominan peripheral vision.

SQ optometry wouldn’t allow me the proper glasses. They gave me standard PIA pieces of shit – state glasses. Apparently, I didn’t qualify for them since I didn’t meet any of the prison medical protocols. I had to repeatedly fight for them, advocate for my needs and was continuously denied. Once again it took the compassion and clout of others outside of the prison medical system, to help me advocate all the way to the warden, Ron Davis to get my glasses. I’d like to note also that the prison did not have to pay for these glasses, my family was responsible.

I went to the board in early February of 2019, and was deemed suitable to go home. I thought I still had a year to prepare for my release and had planned on taking advantage of every second to organize my plans. Unbeknownst to me, my time had been significantly shortened by both the programs I had attended as well as my work in the prison library. I was informed of my early release through the prison mail. However, when I looked at it and calculated the time, I thought I had shortened my time by two to three weeks. So, I went to see my counselor, who of course wasn’t in, but I was able to talk with another counselor. Upon further examination, she too realized I had extra credits, and that I was to be released nine months before my original date. If I hadn’t checked with her, I would have continued to prepare myself for release, doing time for another year. I paroled in December of 2019 right before Covid hit.

I advocate for my fellow autistics both inside and out and everyone impacted by incarceration to give them as soft a reentry landing as possible, rather than the hell I and others have gone through.

And I won’t fail…I won’t go back.

If I can do it. So can others.

Two days before I was released, the prison’s pre-parole counselor came to talk to me. He said, “Your acceptance to your housing, HealthRight 360 has been rejected. They have no beds.” Shocked, I said, “What are you talking about, where can I go? My parole agreements are purely mental health, and I can’t just go anywhere.” He responded , “You’ll be fine, you can either go to Hayward or Oakland.” And that was how I found out that the Mental Health Facility that I was counting on was not an option for me. Just like that and right before my date, as if it was nothing. I had spent months securing the most appropriate housing knowing this was going to be an unsettling time in my life. Things quickly turned into a horror show.

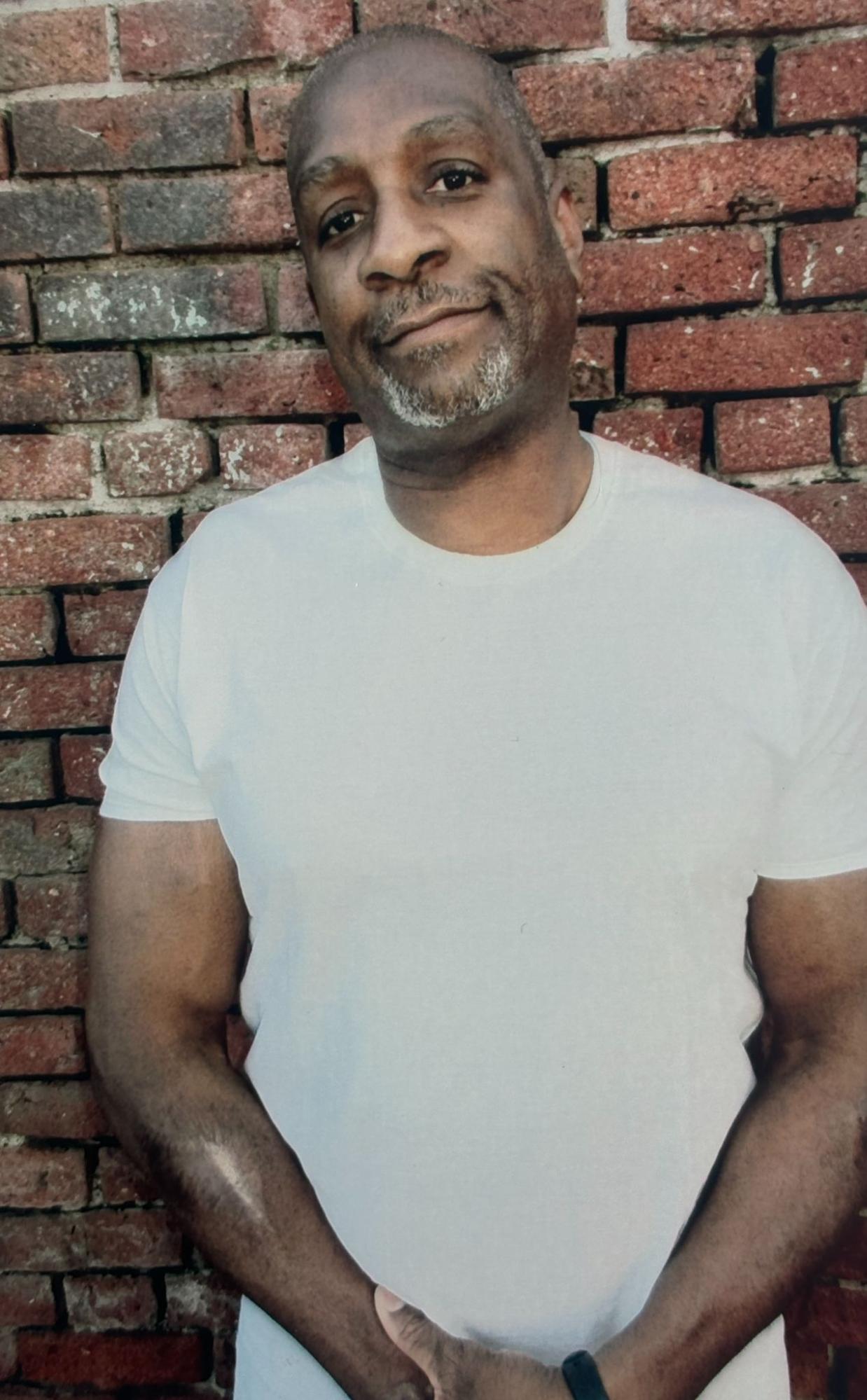

The day of my release was here. My mom and dad and even my little sister were at the gate waiting. It was earth shattering. I hadn’t seen or spoken to my dad in fifteen years and had only been in contact with him four times since my sentence. After my parents’ divorce when I was ten, they were distant figures in my life. My childhood was stained with a bitter sense of betrayal, intensified by my semi-formed adult recognition of what was happening (at the time, I was undiagnosed). I had been close to my sisters before I was arrested but afterward, it seemed we were all strangers. I had a sense they’d be there, yet I had no expectations. My dad came over and gave me a big hug, “It’s over,” he said. I could not have chosen better words myself. They still ring in my head today. I had become self-sufficient in multiple ways. Hooray for therapy, it was only because of my years of hard work that I could handle what was being thrown at me.

After my first meal in the free world with my family, a wonderful guy by the name of David Cowan, from an organization called Bonafide, drove me to a transitional house, called Volunteers of America (VOA), in Oakland. David inadvertently prepared me for the worse and he didn’t do it justice. It was a shithole, hell. I was put into a ten man dorm surrounded by people I did not know. I had no idea how to react. I had zero time to process the transition and because of my autism, I was traumatized. For the first two weeks, I sat on the edge of my bunk bed, withdrawn, constantly in grips of powerful anxieties. I only got up to use the bathroom. My autism proved to be especially challenging in that environment. I found myself struggling to cope with the changes occuring in the span of those few weeks. I was unsure of my next move or my plans. My well thought out future was quickly falling apart. Thank God that only lasted 14 days. My parole officer was able to transfer me to San Francisco to a reentry house. There I was able to recover and begin rebuilding my plans of reentry.

By a happy accident, today, I live in a communal housing project in San Francisco called Second Life. It is designed as an intentional community with people both previously and never incarcerated. It was created by people who want to live together. A combination of both desperation and force led me here, and I am so grateful. Here, I have my own room, my own space. It shows us what we can learn and how we can grow from being human together. Here, we are a community – we bolster each other and we look out for one another. We learn together. I have my room now for as long as I want it and am supported by the community; they learn from me as I learn from them.

It has been quite a journey for me, from my years inside prison, to being released. As I became empowered after learning that I am a high functioning autistic, to being found suitable by the board, to being released and dealing with the challenges that came with that transitioning process. The struggle isn’t over; but the stress and the pains I’ve overcome have been greatly reduced. And now there are way more positives than negatives in my life.

Joe,

I am grateful that you have come through this inexplicable time in your life and that now you are on the “other side” of it. Great job being your own best advocate, that is what I strive to help my high school students establish within themselves.