The Prison Podcast Episode 4: Hurt People Hurt People

January 8, 2025

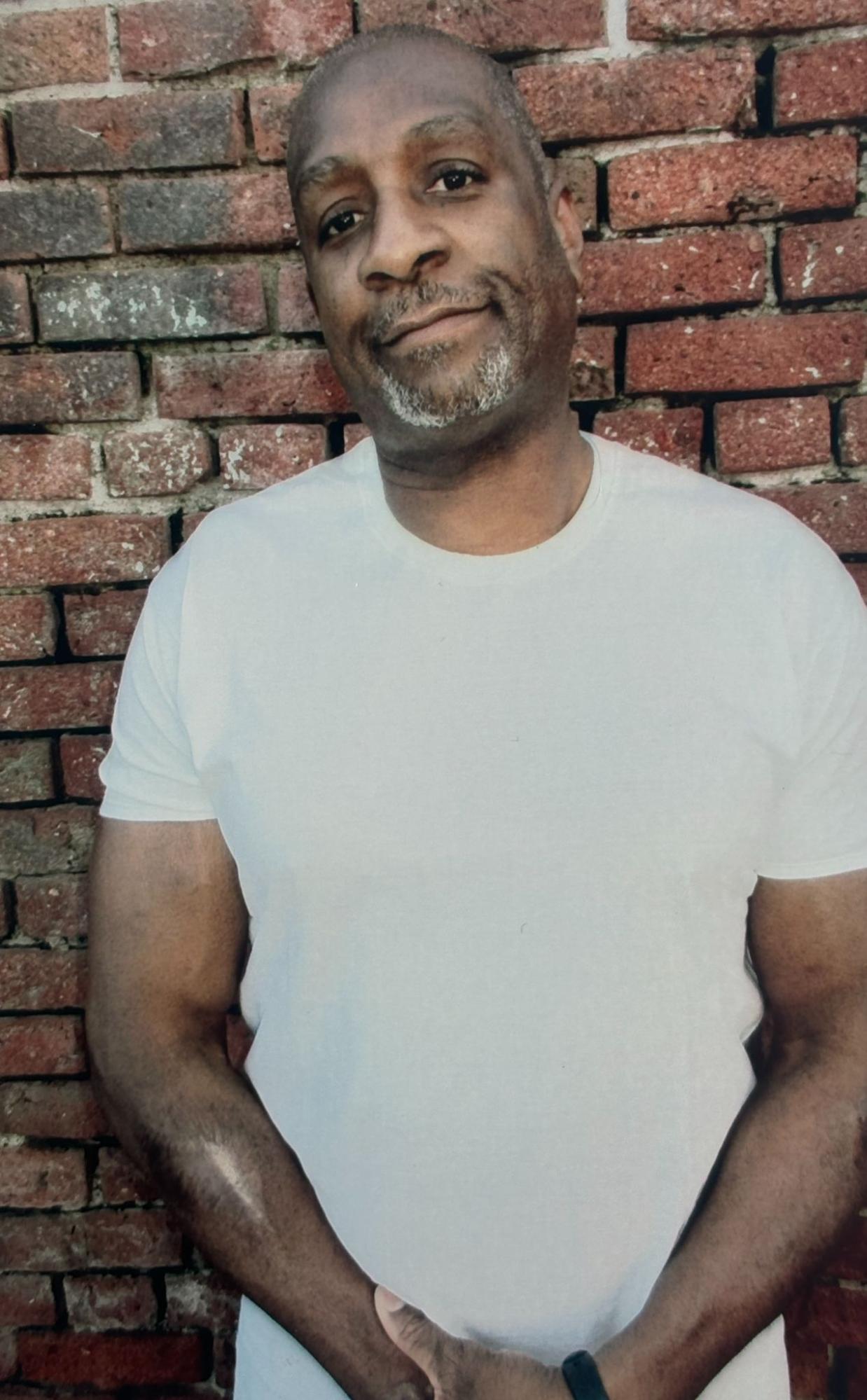

Today’s guest is Christopher, who served 25 years in various California prisons as part of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. During his time in prison, he acted as Jane’s surrogate in their Victim-Offender Dialogue.

In this context, a surrogate is someone convicted of a similar crime, though not the perpetrator of the offense against the specific victim. The surrogate’s role is to help bridge the gap, allowing the victim to express their experience to someone with a shared history of offense.This creates an opportunity for healing and reconciliation, especially when victims are unable or choose not to confront the actual offender but still want their voices heard.

After more than two decades of incarceration, Christopher has been released and is adjusting to life in the free world. Navigating the challenges of reentry, he faces the task of catching up on the technological and cultural changes that have unfolded during his time in prison. But Christopher’s story is about more than reentry. It’s one of deep personal transformation.

This episode addresses a difficult and sensitive topic: a sexual crime committed against a child. Christopher, who has been open about his past, is here to discuss the painful reality of his actions. His willingness to confront and share the truth about his crime is both courageous and impactful. This conversation is not just about personal accountability; it’s a sobering reflection on trauma, human behavior, and the potential for change. It’s a raw, powerful discussion about forgiveness, healing, and the challenges of facing the darkest parts of one’s past.

Transcription

Michael: My name is Michael, and I’m the communications director for San Quentin. This episode contains strong language and graphic descriptions of violent crimes, including possible references to sexual assault. This podcast is intended for mature audiences. Listener discretion is advised.

Diane: Hello, and welcome to The Prison Podcast. I’m your host, Diane Kahn, Executive Director of Humans of San Quentin, and we’re so grateful to have you with us today. The Prison Podcast amplifies the voices of survivors of violent crimes alongside their convicted offenders, shedding light on stories that are often excluded from public conversations. This podcast explores the transformative process of victim-offender dialogue—a facilitated meeting within a prison setting that brings together individuals who have experienced harm with those responsible for it. Each episode features a candid conversation with someone who has completed the extensive victim-offender dialogue program. These discussions offer profound insights into the power of vulnerability and self-reflection, illuminating the complex relationships formed through harm. Unlike traditional true crime media, The Prison Podcast emphasizes personal agency and the journey of reconciliation. By shifting societal attitudes and fostering emotional connections, our goal is to inspire individual change, promote healing within our communities, and encourage a more compassionate understanding of justice. Thank you for joining us as we explore these powerful stories of healing and transformation. Today, we’re joined by Christopher, a survivor of repeated sexual assault whose resilience shines through the shadows of past trauma. His journey has been marked by deeply sensitive and challenging experiences, including moments that address issues involving minors. With that in mind, listener discretion is advised.

Christopher’s openness and strength in sharing his story offer a powerful perspective on healing and hope. I’m honored to sit with him as he reflects on his journey and the strength that has carried him forward.

Christopher, thank you for sharing your heart and story with us today.

~~~~~~

Christopher: Thank you for having me. I’m glad to be here.

Diane: It sounds like you’re setting a compassionate and respectful tone for this conversation, allowing Christopher the space to decide how much of his story he wants to share. It’s important to create an environment where he feels safe and in control of his narrative. Would you like me to suggest how Christopher might begin, or would you prefer I stay focused on the conversation?

Christopher: Well, I guess we should just get right into the heart of why I was in prison. I was incarcerated for rape and the kidnapping of two teenage girls at two different times, a few months apart. They didn’t know each other; they were strangers to me. I abducted them and sexually assaulted them. I was convicted of both crimes, but at the time, I didn’t take responsibility. It took me some time to figure that out and understand how to do so. I was ultimately sentenced to 96 years to life. I served 25 years due to changes in the law, which gave me the opportunity to go before the board. In my initial hearing, I was found suitable for release. Since then, I’ve been out for about six months. During my 25 years in prison, it took me a few years to come to terms with my crimes and take responsibility. I was in a state of delusion and denial. I couldn’t ignore the fact that I was in prison—my delusions were crumbling around me. Once I faced that reality, the truth started to set in. I needed to figure out why I had done what I did, especially considering the loving and nurturing background I had growing up. I came from a stable, middle-class home with two parents who cared for me. I had a great life. How did I end up becoming what I now see as a monster? How did I make those choices? I had served my country honorably in the Marines—so how did I end up here, making these decisions? Once that realization hit, I knew I had to change. It wasn’t just about hoping for a chance to get out someday, although I did hope for that. But it wasn’t about finding a way out through the system. At that time, I wasn’t even aware of the changes in the laws that would eventually help me get released. I just knew that if I was going to spend the rest of my life in prison, I wanted to become a better person. I wanted to create some healing, to apologize, to change, and to make the world a little bit better in some way. So I began that journey. I reached out to some friends and asked about groups to join. I started attending a Christian 12-step program, and the first step was the biggest hurdle for me. Like many men, I struggled with being honest. Admitting that I was powerless was a tough thing to face. But once I took that step, it was incredibly relieving to finally be honest and take responsibility. For me, accountability is about more than just admitting what I did—it’s about trying to make things right. About 20 years ago, I started on this path, though there was a gap in those 25 years. It took me about five years to come to terms with everything and finally say, “I need to do something.” It was a long and difficult process, but I began by telling my family that I was responsible for my actions. I also started attending groups, learning about why I had committed those crimes, and taking the necessary steps toward changing my life. Ultimately, the biggest influence on my life was the sexual harm that had been committed against me. I was a victim of sexual assault by three to four different people. In my mind, my memories of these experiences are fragmented because, for years, I tried to bury them. But no matter how much I tried, I couldn’t erase them, and they profoundly influenced the decisions I made in my life. As a child, I couldn’t forgive myself for letting those things happen. I thought there was something really wrong with me because I was the one experiencing them. So, I did the only thing I could to cope—I denied that it had happened. It wasn’t just pretending it didn’t happen; it was splitting my reality. That was the beginning of how I could be a good person in one area of my life while being a horrible person in another.

Diane: I’m not sure how comfortable you feel talking about this, but I haven’t really heard from anyone who has committed the kind of crime that you have. Would you be willing to go into more detail about the crime itself—what happened and what you were thinking or feeling at the time?

Christopher: Growing up, I had outlets to express the anger and rage I carried inside. Sports were a big part of that—athletics became my way of proving my manhood. Then, I joined the Marines, which gave me another outlet, allowing me to channel my anger and rage through violence. That theme of violence ran through my life. But when I left the Marines and returned to civilian life, I no longer had those same outlets. I didn’t have sports or the military, and that anger didn’t just disappear—it stayed with me. It turned into a toxic belief system: hurt people before they can hurt you, take advantage of the weak. My view of the world became extremely distorted, but I kept it hidden from others. It’s crazy because these delusions were so twisted that they don’t make sense to anyone who hasn’t experienced them. I could be a good person in the community—working with others, and doing positive things. But at the same time, I was living as a monster at night, victimizing people. I was married at the time, but I was constantly cheating on my wife, with no remorse. I hid everything. I was living a double life. During the time I committed my crimes, I found myself driving around, looking for prostitutes. That’s when I encountered my survivor. She was a teenager. I picked her up, forced her into my car, abducted her, and assaulted her. Then, my delusions kicked in, convincing me that she must have liked it because she didn’t resist too much. I was so disconnected from reality that I even got her phone number and later called her to meet up again, believing she really wanted to see me. That was the depth of my twisted thinking. I was arrested when I went to meet her, and the police were there. As for my second survivor, I wasn’t caught for that crime until after I was already convicted. It was a cold case. In reality, she was my first survivor—the first person I assaulted. The crime happened in a similar fashion, but I didn’t know her. I forced myself on her, abandoned her, and she called the police. But at the time, the case didn’t go anywhere. It wasn’t until I was convicted of the second crime and my DNA was entered into the system that it matched, and I was convicted for that assault as well. It took me time to understand why I had done these things. My actions were driven by selfishness and deeply distorted beliefs. Those beliefs shaped the way I thought, how I used sex as a coping mechanism, how I viewed women, and how I treated them. My perspective was rooted in womanizing and toxic masculinity—those were the core influences in my life. Processing all of this was difficult, but eventually, I realized that the source of it all was my own victimization. However, I don’t want to use that as an excuse—because it’s not. It was an influence, but ultimately, I made my own choices. I could have asked for help, but I didn’t. Instead, I chose to stay trapped in my delusions. I chose to act out. I take full responsibility for all of it. Nobody else is to blame—not even those who harmed me in the past. I made those choices, and I am 100% responsible for the pain I have caused so many people.

Diane: Wow, thank you so much for sharing that. I’ve only ever heard about people like you through the news, so hearing someone talk about it so openly is incredibly eye-opening. It’s interesting to hear about the mental and emotional space you were in during those moments when you made excuses for your actions—why you thought it was okay. It sounds like one of the women came to your parole hearing—was that during COVID, when it would have been over Zoom? Tell me more about that. How did you prepare yourself for that moment? What was the process leading up to it, and what were your feelings surrounding the experience?

Christopher: By the time I got to the board, I had been doing a lot of recovery work. I had been working with AHIMSA, a program in prison, which helped me realize a lot of things. It allowed me to uncover the trauma I had experienced and understand why I behaved the way I did. There’s that saying, “hurt people hurt people,” and I came to realize that because of my own pain, I had been inflicting pain on others—not in a compassionate way, but by passing it on, just as it had been done to me. That’s how I lived my life at the time. Once I started to understand this, I became more willing to be vulnerable and share my experiences—what had happened to me and what I had done. It really broke me open in a way I had never experienced before. For the first time, I was able to talk to my family about what happened to me. I hadn’t been able to do that until I was almost 50 years old. When I told them, they were shocked and blamed themselves for not seeing it. That was hard to watch because they took on a lot of responsibility for something they didn’t cause. A lot of parents do that—they blame themselves. But the truth is, it wasn’t their fault. It was the people who harmed me. For many survivors, though, there’s that internal question: “What did I do wrong? Why me?” And that’s where a lot of the shame comes from. But it had nothing to do with me—it was about the people who victimized me. In the groups I attended, especially the Realize group, we had the opportunity to talk to other survivors. That’s where I met Jane. I was able to share with her why I did what I did. I was also able to answer that question for myself—because I was both a perpetrator and a survivor. I wanted to understand: Why me? Why did these things happen to me? And I realized it wasn’t about me. It was about the people who hurt me. That’s what I was able to explain to Jane—it wasn’t about her; she was just targeted by the person who hurt her. For survivors, understanding that they’re not responsible for someone else’s actions can be such a relief. I think hearing that helped Jane find some understanding, and that was important. Going into the parole board hearing, of course, I wanted to go home and see my family again. But I didn’t go into the hearing just thinking about that. My real goal was to have my survivors present, so I could tell them directly how truly sorry and remorseful I am for what I did. I wanted them to hear that from me—how I robbed them of their futures, how I stole experiences they should have had, and that I understood the pain and trauma I caused. I wanted them to know I understood how their lives would be affected long after the assault—the fear, the PTSD, all of it—and that I never took any of it lightly. There were moments in that hearing where I was blunt with the board. I told them, “I didn’t care about people back then. I only cared about what I wanted. I wanted to escape how bad I felt about myself, and I thought hurting others would make me feel better. But it never did.

Diane: Can you break that down a little bit for me? Because I’ve often said that the act of rape is not so much about the rape, but about getting control of someone. Can you speak to that?

Christopher: There’s something called a “zero state,” and essentially, it’s this feeling of being so out of control that you can’t control your own life or the things happening around you. Whether it’s true or not, whether it’s just my perception, I felt like I had nothing under control. On the outside, I was pretty successful—I had a good job, a big house, nice cars, clothes, money—but it still wasn’t enough. I thought I was a failure. That’s how I saw myself. People might have looked at me and thought, “You’re a winner, bro,” but I didn’t see it that way at all. There was this voice inside me, like the little kid inside, constantly saying, “There’s something wrong with me. I’m not getting what I’m supposed to get. I’m not having what I’m supposed to have.” It was this feeling of never being enough. So, if I couldn’t control my life, my biggest urge was to find something I could control. And the way I went about that was through what happened to me. As a kid, I didn’t have control when I was victimized, so my mind twisted that into, “If I can control someone else, maybe it will make me feel better.” Sex became a coping mechanism, a way to deal with that overwhelming sense of powerlessness. It made me feel better for a little while, but it was never a true, fulfilling feeling. It was always temporary. I couldn’t commit emotionally or spiritually in my relationships. My marriage was falling apart, and I couldn’t be vulnerable with my wife. I had never told her about what happened to me as a kid. I was too ashamed to open up. By withholding that, by not sharing those experiences, I was denying the authenticity of my relationships. In my mind, I had this belief that everything would eventually end, so I’d better get the better end of it while I could. There was this mentality of, “Let me hurt you before you hurt me,” because I believed that people were always going to hurt me. So, I had to get in first. That mentality came down to control. “I’m going to take control of this situation. You’re going to do what I want, and I don’t care about what you want.” The distorted thinking was always there—it was about me getting what I wanted. Sex didn’t matter in and of itself; it was just about satisfying my cravings. It didn’t matter what the other person wanted. And that’s what it boils down to: selfishness. I thought, “I can make her do what I want because I’m stronger, and she’s weaker.” I think that’s a common experience shared by many offenders. From my own work and studies, I’ve found that a lot of offenders have this twisted sense of control—where they feel they have to dominate to feel powerful or validated. That’s what I’ve found to be the underlying theme behind these crimes. There’s a sexual component to their coping skills—sex, masturbation, pornography—and it turns into this delusion, this distorted thinking about control, self-worth, and negative views of the world. For me, it all boiled down to this state of feeling awful about myself. And in my mind, what would make me feel better was having sex—and having it with her, just because I wanted it.

Diane: Interesting.

Christopher: One of the questions posed to me during my parole hearing was, “If this person knew you, one of your survivors, wouldn’t she have told on you? Were you afraid? Did you intend to kill her?” And I said, “No. I got what I wanted. I didn’t need to go that far.” I was satisfied. I didn’t care about the consequences at the time. They were insignificant because I lacked empathy—for her or myself. If I had empathy for her, I wouldn’t have done what I did. If I had empathy for myself, I would’ve avoided putting myself in a position where I could get caught—I would’ve cared enough not to take those risks. But back then, I didn’t care. I didn’t care about being safe or strategic. I just went ahead and committed my crime. Looking back, I realize how impulsive it was—though it wasn’t entirely unplanned. I used to imagine these scenarios in my head where I could take advantage of someone. It became a game to me. Even when I was cheating on my wife, I was lying to other women, pretending to be single when I wasn’t, deceiving them. And now, in hindsight, I see that as a form of assault. It was a fraud, a game to see if I could trick someone into having sex with me or into having a relationship with me.

Diane: That is a lot, Christopher. That’s a lot to take in. I think what stands out to me is the shame you felt. You didn’t want to tell your wife, and you didn’t tell your family because you took that burden all on yourself. And, to me, that seems like the crux of what propelled you into what you did, and the damage caused—not just to you, but to everyone involved. Would you be willing to share with me a little bit more about what happened when you were a child? Can you talk about an incident or something that happened during that time?

Christopher: Yeah, I mean it’s fragmented. So it’s not a clear view because again, like I said, I spent so many years denying it and trying to. Yeah. Blockout images, but I remember at five years old, two older boys, were probably kids themselves. I knew they were kids themselves who would molest me and another boy and sometimes it would have us perform sexual acts on each other and that happened over, I think, months, maybe even a year for as long as I lived in that apartment complex. Then later on, I think I was about seven years old. And my teenage babysitter, who I had a crush on, lured me into my room and molested me. And a lot of this is even fragmented. Even though I enjoyed that because I liked her, it was still a violation of trust. A violation of the trust of my family, me, distorting my love-sex relationship. Or the idea of a love-sex relationship. And that went on, I just, I think a couple of years, I remember incidents where we were alone or I was, she was my next door neighbor, so I would see her all the time and she would have me touch her or she would touch me. And, but I think I thought that was, to me, I thought that was thrilling as a kid, I didn’t feel so ashamed of it, but I couldn’t tell anybody about it. That was a no-no. So when we weren’t around, she would treat me badly. Like: what are you doing here? I was one of her brother’s friends. So it was this front where one minute she’s treating me like some stupid kid. And the next minute she’s touching me and making me touch her and we can’t talk about it. And then from that same family, one of the older boys who was a few years older than me raped me in his backyard.

And that I felt so humiliated, so ashamed. And I thought there was something wrong with me at that point. Cause it started to kind of, cause I was about 10 years old. I was an athlete already. And I was a wrestler too, so I thought, why didn’t, uh, I fight, why didn’t I fight this guy off? How come I didn’t fight? I must’ve wanted, man, there’s something wrong with me. I must’ve wanted this, which goes into the thinking later on in life. Oh, they must’ve wanted to, they didn’t fight. So those things just kind of reoccur in my life. The different aspects of each of those assaults. Reoccurred in my life and how I treated people, how I treated women. Another time he attempted to assault me, but this time I fought him off. And at that point I was like, okay, I’m going to have to use violence to keep people from hurting me. And then other things were reinforcing those ideas of using violence. I was in sports already. My dad was a high school coach, but I was just a kid. And so I used to hang out with a lot of high school kids that were older boys. And I was like the crash test dummy, Hey, get Chris to do this. So to fit in, to be part of the crowd, I would do these risky behaviors to prove my manhood because it was always that doubt in my mind that when I was raped by this boy and I didn’t fight him off I must be gay or something maybe I liked it. Maybe there’s something wrong with me. So I had to fight that, that idea that no, no, I’m not, I’m not gay. I have to prove my manhood. So every chance I got, I proved my manhood and that’s where the development of beliefs, thinking about being a man. What a male is, males don’t show emotion, males use violence, only accepted emotion is anger. All, those themes kind of played a role in, my development, in my thinking. So, after high school, I wanted to join the Marines. Why the Marines? Why not the Army? Why not the Navy? Why not the Air Force? If you watch any of the branch’s commercials, there’s a difference between the Marines and the rest. The other branches show you about career, about going to college, About getting the skill. The Marines, all they show about is kicking somebody’s butt. And that’s what I want to do.

Diane: I didn’t realize that.

Christopher: realize that. If you think that the next time you watch the commercials, you see the Marines, they look good in their dress blues in a fight. They don’t talk about, Hey, join the Marines so you can be, go to college, join the Marines so you can learn how to be a technician, join the Marines if you want to fight if you want to be the few, the crowd. And that’s what was so appealing to me I wanted to be, I wanted to be the tip of the sword. I wanted to be at the front. I wanted to be in the fight. I wanted to kick somebody’s butt from all that anger. That’s where I came from to prove myself. So I would do the craziest things when I was in the service. And I found that I was successful and it was encouraged to be such a risk taker, to be so out there in the Marine Corps. It’s like a collection of the captains of the football team of every high school in the country. It’s like the top athletes and you’re competing against those guys. So I just, again, I would just do some of the craziest things to prove that I was tougher than everybody else and I found a lot of success in that.

Diane: That’s crazy how that you got that image in your head and it fits so perfectly with your defense mechanism to survive and then also get your needs met of feeling in control looking for that point in your life where you’re a person that’s in control that has your life together and looking to satisfy yourself and it seems how I read it is just a path to being normal, getting back that kid that had all that damage done.

Christopher: And I had to learn how to forgive that kid, that he was not an adult. He didn’t have mature thinking. He couldn’t make the decisions. He did the best he could. And I forgive him. I forgive him for the decisions he made and he got me to be who I am. And I thank God for my family, that they were so loving and caring, even though I didn’t trust them enough to tell them, they taught me a lot of things and influenced my life in a positive way where I can be accountable. I can figure out how I made these mistakes, how I made these terrible decisions. And be accountable, be responsible for him. My family taught me that. To be responsible. And it took me a while to get there, but I eventually got there. And with their love and their support through the years that I was in prison, it helped me. It helped me get there.

Diane: When you talk about your family, who do you consider that to be?

Christopher: My mom, my dad, my sister, and some extended family.

Diane: So a person that comes to my mind, as you’re describing this, you’ve got a wife who you’re cheating on, and then you commit your crime with, can you talk a little bit about her and what she was going through?

Christopher: I don’t have any more contact with my wife. We divorced when I think just a couple of years after I went to prison. So we didn’t have much contact after that. She moved on with her life and everything like that. She got remarried. But oh, yeah, I think about how through my understanding through my work in domestic violence, I was a domestic abuser. I’m not trying to mitigate or anything like this, but I didn’t physically harm her, beat or slap her, or anything like that, but I emotionally terrorized her. I emotionally, and spiritually harmed her. I was unfaithful to her. I don’t know whether she knew it or suspected it, but I cheated her out of a marriage. I wasn’t genuine with her. I almost feel like I deceived her into marrying me because here she thought she was marrying this person, and she was marrying somebody else. I know I caused her a lot of emotional distress. Anytime that she may have suspected that I was cheating, I gaslighted her. I made her think, no, you’re crazy. You’re There’s something wrong with you, for you to think, I would do something like that to you. I just told her so many lies and so many untruths and stuff that, I know harmed her dramatically. And I’m glad that she found somebody and got remarried, but I’m sure it was so hard for her to trust somebody. I think too that maybe this shot was her fault. Cause as I said before, a lot of times survivors, we think it’s our fault. Something must’ve been up with me that he would do something like this. And then the embarrassment and shame of having your husband go to prison, losing your house, losing your life, the life that you thought you were going to have, losing the future that you thought you were going to have, and I just didn’t hurt her, I hurt her family because I betrayed the trust. So I think that she had a tremendous amount of pain due to me. I caused her so much pain and heartache. I hope that one day I can apologize to her, but, I don’t want to bother her in her life by reaching out to her, I think with modern technology and through the friends that I have that I think she may have heard by now that I’m out, and if she wants to talk to me, I’ll talk with her and I’ll have to need to apologize to her, but I think I’ve done enough damage to her in her life that I don’t need to inflict anything more by reaching out to her.

Diane: Well, you’re so kind. Like we talked about at the beginning of the call that just pervades me for you, just kindness. You’re very sensitive, but you’re also so self-actualized. You’re able to look at what you’ve done talk about it and learn from it. And all the therapy, it feels like you’ve gone through, even though it may not be as traditional as we see it out here, because, in prison, you’ve got to dig deep down and do it alone and sit in groups and share it with other people. And then to be able to talk to your victims or survivors in this case

Christopher: I like to correct something. I’m not doing it alone. I have guys in these support groups. They’re with me. My brothers, the supporters and staff that come in to run these groups, their input, and their impact is tremendous. So it’s not alone. And that’s one of the things I think I learned going to a group that my experience is not unique. Other people have experienced that. And that’s one of the things that Shane keeps you from realizing is that you’re not alone. There are a lot of people that go through this and because you think you’re so ashamed you think well this is just happening to me. I can’t tell anybody about this. Nobody’s gonna understand and when you start going to groups you start opening it up. You start hearing guys tell their story and you think I’m not alone. This guy went through the same thing I went through. And so this is not a lone journey. This is a journey that I’ve taken with many other people in my preparation for the board. I had friends help me and some of them went to the board, not to say the right things. Just to hash out the answers the board would have to talk about these things, explain, explain yourself, explain why you did what you did. I think that’s why I sound, it’s like you said, I can articulate this way because I’ve been speaking about it. One person told me in my therapy group that I go to parole. said you speak so matter of factly, like, so absolutely about your crimes, about the things you’ve done. It’s almost unfailing, like callous. And I just, I had to share that. Well, it’s not that I don’t feel anything. It’s that I’ve cried for many years. And there’s a point where you just, you stop crying about things, the harm you caused, you feel it, but you don’t let the shame get ahold of you and where you’re feeling so bad that I can’t even look at you. So I’ve dealt with all those emotions. And I still feel the horribleness of what I’ve done. I didn’t know the impact of what I’d done, but when I speak now, I speak with accountability. So there’s no mistake when I say I raped somebody, I did that. Not, well, I kinda, I sexually assaulted somebody. I use the language of accountability. So when I talk about what I imagined they went through, that’s being accountable. That’s not mitigating anything that they are justifying anything that they experienced. I want to know everything that they experienced because. That lets me know that’s what I did. It reminds me that’s what I did. Now I’m not that same person anymore, but I was a maniac. I was a monster at one time. I’m not that person anymore. So I can speak about that scary person like it was somebody else. But I know it was me. It was something that I did. So I’m not afraid of it, and I battle shame. I want to make sure that shame has no role in my life. So when I speak about things, I can speak about them openly without any hesitation. And if I say something incorrectly, or if I say it wrong, okay, I’m okay with that. I’ll learn from it because this is a learning experience. I don’t have all the answers. I don’t have, I’m still a work in progress. I’m still learning, and gaining deeper insights into what I’ve done in my life. Connecting the dots better and all that is just to make me a better person and to somehow make amends for the things that I’ve done

Diane: You hit on so many important things and I think when you think about what you and I are building today, this podcast is for people to listen to. There are people out there who feel alone. They’re hearing your story. They can relate to it. They’ve either been the victim or the survivor. I mean, you alone, Christopher, encompass so many different parts. So it’s wonderful that you found that ability to be able to be in a group. And some so many people are free today that they do not go and seek it. They’re afraid of it. They don’t know where it is. They don’t trust the people in that room. So I think if there’s one message that I’m hearing loud and clear from you is those people that can identify with any part of your story that may know someone that can identify with any part of your story, they need to get out and talk, talk, talk. You could work through that and do this healing. And that’s one thing I hope for you and talking today that people hear it, hear that healing within yourself. I mean, You had mountains to go through of those different people in your life that taught you that manipulation. And for me, it came out clearly when you’re talking about the older babysitter, the girl, she taught you manipulation at a very young age as this is how you’re going to act around me. This is how I’m going to treat you, but these are my feelings. And this is really what I want. So that. The juxtaposition of your brain that had to form into that at such a small age of having the feeling of being wanted and being hated and having to hide things that aren’t natural from your parents and your family and to have that happen in so many, three separate incidences that you talk to is. amazing that you can get through one, but then get through three. And then it’s even hard for me to bring up what it is that you’ve done to these teenage girls and the violence and the abuse and the violations that you brought to them. But yet you’re at the same time, very able to talk about the word accountability and being able to accept what you have done and look at it for what it is. It’s just, very cathartic to hear from you because you’re every aspect of what happens to a child with harm and how you reacted to it and the normalcy that I see of it and how it then led you to those crimes, so I want to share that I’m in awe of everything you’ve done and to be able to take the shame away from you from when I hear that It’s very controlling for people and how they live. So I have an admiration that you’re able to identify us with all these emotions and what you’ve gone through. And you’re at such a point that we should reach acceptance, right? You’re a person that each of us needs to look to when we have these doubts and Then you told me at the beginning of you and I talking today, how thankful you are.

And you’re happy to have your 1st apartment and be on your own. And you’re thankful for your days and the sun and talking to people. So, I don’t want to put words into your mouth. Is there? A message that you would share with people who are listening.

Christopher: Yeah, I think there’s a lot of things I would love to share with people, especially since this is in San Quentin, I’m sure that guys in prison will, will hear this. So the first thing I like to say is Like you said: you have to open up and share, you have to tell your story, and you have to allow yourself to be vulnerable. If you’re a tough guy and you believe that you’re a tough guy, things don’t hurt you, then beat shame, beat it. Don’t let shame control you. Don’t let shame make you fearful of talking about what you’ve experienced in your life, the harm that you’ve experienced. And how that shaped your thinking. So that’s what I would say to resistant people is that what’s holding you back is a shame. The other thing I’d like to say is this. I think often the challenges that I face being out here, sometimes are tough, the tough things to go through. And when I feel things are getting kind of hard, I remind myself of this. My worst day out here is light-years better than my best day in prison. And for guys in prison that are listening to this, what’s your, think about what’s your best day in prison. For me, it was like this: getting the package, going to the canteen, getting a visit. Watching something good on TV, my team winning. That was like a great day for prison all in one day. That’d be a great day in prison. That is nothing compared to being out here on the streets, seeing the world, being able to put my toes in the sand, and watching the surf rush up. Trump’s that every day. I’d much rather be out here looking out from under a bridge. If I had to live under a bridge, then looking out of a cell. So. Just remember that, work your hardest to get out of prison, do what you have to do to better yourself, to be a better human being, to leave a healthy, healing ripple effect rather than a negative ripple effect.

Diane: What message would you have for people who are listening free people as we call them who have been a victim of sexual assault

Christopher: The same thing. Don’t let shame hold you back. It’s not your fault. If you experience these traumatic events, it’s not your fault. What somebody did do to you? isn’t a reflection on you at all. It has nothing to do with you. You’re a beautiful human being. You deserve to be loved. You deserve to be validated. So don’t let shame keep you from being that person. Go seek help. Go talk to somebody. Share your story and you’ll find out you’re not alone. There’s so many of us who hurt people out here and we need each other to heal.

Diane: And how would you speak to someone who was the Christopher before he went to prison who was there and taking control in your case of a young woman’s life? How would you talk to someone who’s in that situation? Or how would you talk to yourself before that?

Christopher: Such a difficult thing. But I think I told a little story about a man that I work with who talks about crime. I think I would paint the picture of the consequences of their actions to illustrate how not only are you going to hurt somebody, but you’re going to hurt yourself. You’re going to get yourself thrown in prison or worse. You’re going to hurt your family because they’re the ones that are going to be there for you. If you have children, you’re going to abandon your children to whatever their life circumstances are going to be brought to them. You’re not going to have any control over that. You’re going to be in a hell hole and you’re going to have to live with that. The gravity of what you’ve done. So if there’s a way for you to seek help, seek help because you’re not going to do it on your own. You’re not going to make yourself better. You’re not going to just say, well, I’m just not going to do that. There’s thinking there are beliefs that are tied to your behaviors. So you have to change your thinking. You have to change your beliefs. If you think this world is a screwed-up place and that it’s the survival of the fittest, then you need to change that belief. It’s not a screwed-up place. It’s a beautiful place. There are so many beautiful people in it. There’s love, tremendous love in it. And it’s there for you. You just have to go out there and speak it. You have to make it happen. You have to go and ask for somebody to help me.

Diane: Yeah, that’s powerful, so powerful. You just want people to get up and do it. Go ask for help. Take the journey with someone else. There are people out there who are professionals, people who will listen, people who can help get you through it. Even if they’re not professionals, they’re people like you, they can sit next to them.

Christopher: They’ve been through it. I have a couple of friends who have been going through depression. I speak to them about all that. I make myself available to them and I’m not a psychologist or a doctor or anything, I don’t know all the ins and outs of depression, but what I do tell them is, that you can’t just let a thought go away, you have to make it go away. Some of my friends say, well, when I have these thoughts of suicide and stuff, I just try to hold on and just not think about it anymore. And I say: you can’t do that, you have to make yourself not think that you have to argue with yourself about what a great person you are, what a beautiful human being you are, you have to argue with yourself about that because the suicide ideation, the depression is triggering these negative feelings about you and these negative feelings generate negative thoughts and they just don’t go away. They may go away for a while, but they come back. So you have to combat them by thinking positively by making yourself think, well, this is not right. I’m just thinking this way because I’m feeling sad. I know I’m a good person. I know I’m valued. I know it’d be better for me to be in this world than it is to not be. And you had to convince yourself of that. So you have that’s how you change your thinking. That’s how you change your beliefs. You have to work at it. He did a stone coming. On their own.

Diane: Oh, my gosh, you’re such a power and such a force of so much good Christopher and I, and I just wrote that I wrote down what you said. So you can’t let a thought go away. You have to make it go away. You have to argue with it. You have to get yourself beyond it. Get rid of the negativity. So you can say way too much has changed that narrative.

Christopher: Yeah,

Diane: So, yeah, that was beautiful to hear that. You have to work at it. I think about little Christopher. He was five years old and sexually abused, you had to go back there, and realize that there was good, right? That you weren’t that person that happened to.

Christopher: I practiced this, this positive self-talk. When I start thinking negatively or having a negative thought, I don’t dwell. I don’t let it dwell. I start thinking right away. Why am I thinking like this? What is it that’s causing me to feel this way or think this way? And I break it down in my mind and sometimes I’ll be in the car driving and it looks like I might be on the phone talking because I’m talking to myself, I’m talking to myself out of thinking what I’m thinking. So I went on a day trip down to L. A., which is about an hour away from where I live. I was having a great time. I was on Venice Beach. I was hanging out in Santa Monica. But I had to be back because I had a group at the transition home that I lived in that evening as I was driving back. It’s about four o’clock in the afternoon. I’m getting sour about it, man. I have to go to this stupid group. It’s just a waste of time. I’m just having all these thoughts and stuff like that. I’m looking at the beach. I’m reflecting on how what a great time I had. I wish I could stay longer, but I have to go to this group. So I’m driving back. I’m going up by Malibu along the coast. I’m looking out and there’s this beautiful ocean blue. The sun is reflecting as sparkling. And I think to myself: What would I be doing right now if I was in prison? So I looked at the clock when it was like four o’clock and I’m like, oh, I’d be sitting on my bunk getting ready for count. And I thought to myself, what am I complaining about? First of all, I’m driving along the coast of California, beautiful coast, beautiful ocean. I just had a great day at Venice Beach in Santa Monica on the beach. Now I’m driving up the coast and not only that, I got the windows rolled down. I got the sunroof open. I got the music glaring and I’m driving an effing Cadillac that somebody gave me. What do I have to complain about? If I was inside right now, I would give my left arm to be out here dealing with going to a group in the evening. I had to convince myself that what I was thinking was so ridiculous, that I should be happy about where I’m at right now. So that’s what I’m talking about. That’s the example. What am I talking about? You have to push negative thoughts out of your head. You have to convince them that they do not belong there.

Diane: There’s a question that I’m sure you’re prepared for. It’s not like, it’s not an easy question, but it’s a question that I’m sure you’re prepared for. What would you say to the people who think you shouldn’t be out here? What you did Christopher, you don’t deserve to walk the earth. You don’t deserve to be in Malibu. You don’t deserve to be driving your car. What would you say to them?

Christopher: Them? You have the right to believe that. I can’t say anything that will convince you otherwise. Other than that, I am so grateful to be here. It’s not up to me to convince you. I know that there are going to be people who dislike me for what I’ve done, that hold against me, that are going to reject me, but I can’t control that. That’s out beyond my control and I don’t want to control it. You are free to think and believe how you want to believe. And it’s not for me to make you think otherwise if you can look at me and say, well, he’s doing positive things, at least he’s not hurting somebody. If that’s satisfying for you, great, but I’m not worried about what other people think about me or how they feel about me. I have too much on my plate to be worried about what somebody else thinks about me.

Diane: I’m with you. We kind of get that at our age, don’t we? You can’t live through that. We’re good people. It’s so great to hear you be so positive and just giving us those positive nuggets to get us through. We all have that inner critic that pops up for some of us more often than others. Especially sometimes when you get in bed at night and you’re alone, but it also gives a testament to you being in prison for 25 years and still being able to come out and be as positive as you are. So I want to thank you so much, Christopher, for sitting down with us today. You’ve been enlightened in so many different ways. There’s so much that I take away from how much I’ve learned from you today. I think about shame. I think about loneliness. I think about accountability. I think about harm. You’ve got a plethora of information for me and I hope our listeners as well. So thank you for coming today.

Christopher: Well, thank you for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here. I just hope that people can take something positive from this and help themselves and get something that’s going to better their lives.

Diane: I sure hope so too. Thank you. Christopher’s story is both heartbreaking and inspiring. From his challenging childhood and the harm he inflicted on two teenage girls, and many others, to the transformative work he has done and continues to do. He and Jane have sat on stage together and addressed crowds of people, discussing their lives and the power of self-awareness. I deeply admire Christopher for his conscientious efforts to better both himself and the community around him. I eagerly anticipate his future contributions to the world. And Christopher, I want to extend my heartfelt thanks for opening up and allowing us a glimpse into your world. And the life you lived before committing your crime. Your willingness to be vulnerable demonstrates the significant amount of work you’ve put into understanding and transforming yourself. I truly believe your story needs to be heard, and I hope it is received with openness and contributes to healing for all who listen. If you or someone else is interested in participating in a victim-offender dialogue, Please reach out to your local Department of Corrections. For those interested in potentially hearing my unfiltered interview with Christopher, please visit our Patreon account. I hope you find his journey as informative as I have. In our next set of episodes, we’ll be delving into a deeply moving story of loss, accountability, and the power of forgiveness. First, we’ll sit down with Elle, a mother whose life was forever changed by the tragic loss of her daughter, Emily, in a drunk driving accident caused by Allen. Elle’s journey toward healing and her choice to engage in a victim-offender dialogue, provide a powerful perspective on trauma, compassion, and the possibility of redemption. Then, in the following episode, we’ll hear from Alan, who is currently serving time at San Quentin State Prison for his role in Emily’s death. He shares his challenging path to sobriety, his immense gratitude for El’s forgiveness, and his hopes for helping others through his story. Stay tuned. These episodes offer a rare insight into how accountability, remorse, and empathy can transform lives. Be kind to yourself and see you next week.