The Prison Podcast Episode 5: I Have A Hug For You

January 15, 2025

This week’s episode features Elle, a mother who shows us the profound beauty of carrying grief with grace. She faced the devastating loss of her daughter, Emily, in a tragic accident caused by a drunk driver in Los Angeles.

Over time, Elle’s journey moved from grief and anger to a place of healing, ultimately leading her to meet with Alan, the driver who took her daughter from her. Together, they participated in a Victim-Offender Dialogue. Today, Elle works as an advocate and facilitator for these dialogues. She has walked a long path toward forgiveness, and in this poignant episode, she shares her powerful experience.

Transcription

Michael: My name is Michael, and I’m the Inside Communications Director for Humans of San Quentin. The contents of this episode include strong language and graphic descriptions of violent crimes that may include sexual assault. This podcast is intended for mature audiences. Listener discretion is advised.

Diane: Hello, and welcome to The Prison Podcast. I’m your host, Diane Kahn, Executive Director of Humans at San Quentin, and we’re grateful to have you with us today. The Prison Podcast brings forward the voices of survivors of violent crimes and their convicted offenders, unearthing stories often excluded from public conversation. The podcast centers around the transformative process of the Victim-Offender Dialogue, a facilitated meeting within a prison setting that brings together someone who has experienced harm and the person responsible for causing it. Each episode features a candid conversation with someone who has completed the extensive Victim-Offender Dialogue program, offering profound insights into the power of vulnerability and self-reflection. By drawing back the curtain on the complex relationships forged by harm, The Prison Podcast provides a platform for healing, empathy, and understanding. Unlike traditional true crime media, the podcast emphasizes personal agency, the journey of reconciliation, transformation, societal attitudes, and fostering emotional connections through these powerful conversations. We hope to inspire individual change, promote healing within our communities, and support a more compassionate understanding of justice. This season, we’ve shared stories of resilience, hope, and transformation, and today’s episode is no exception. We’re thrilled to bring you the story of Elle, a remarkable mother who turned unimaginable tragedy into a journey of healing and advocacy. In this episode, we speak with Elle, who tragically lost her daughter, Emily, in a devastating accident caused by a drunk driver, Alan. As a mother myself, I’m deeply moved and proud to share Elle’s story with you. During Alan’s sentencing, Elle stood in the courtroom broken but determined, ensuring accountability for the devastating loss of her daughter. But her courage didn’t stop there. Seeking healing, Elle took the extraordinary step of participating in the victim-offender dialogue, sitting face-to-face with Alan, the man responsible for the tragedy. What followed was a powerful encounter where Elle’s path to healing intersected with Alan’s journey to redemption. Drawing from her own family history of trauma and alcoholism, Elle was able to see beyond Alan’s actions to the pain in his past. Together, they began a process of mutual understanding and healing. In this episode, Elle shares her incredible journey—how she moved from grief and anger to advocacy and forgiveness, and how she became a trailblazer in victim impact discussions with people incarcerated. Her story is a testament to the power of empathy, courage, and transformation. I’m so proud to share Elle’s wisdom and strength with you today. Hi, Elle.

Elle: Hi, Diane. It is wonderful to be with you, and I can’t wait to tell the story.

Diane: Can you tell us about your daughter and what she was like growing up and the kind of woman she was becoming as she found her way in the world?

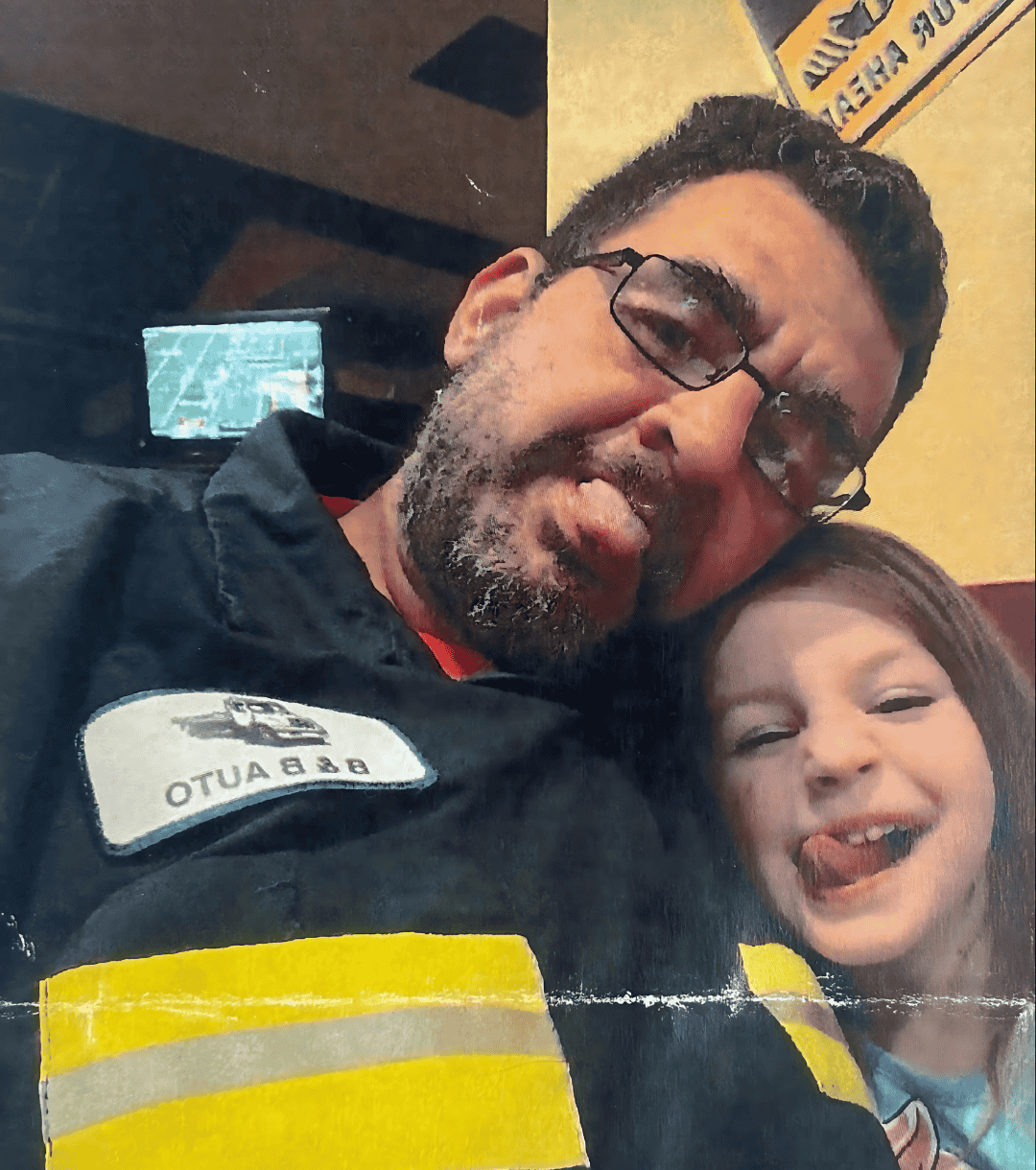

Elle: Well, I had asked for a strong-willed child, a strong-willed girl. When you ask for things like that, you usually don’t understand what that means, because I got exactly that. She was strong-willed. I guess she was maybe eight. And I told her to put a sweater on because it was cold that day. She was getting ready to go to school, and she went, put her hands on her hips, and said, “Mama, I’m not going to wear a sweater because you’re cold,” and that pretty much characterized our relationship. I had to pick my battles. And a lot of things really didn’t matter, like how she dressed. She just was into layers and colors and patterns. And she always looked like a little hippie. I met her once. I picked her up from the airport, and she was, I was watching her come down the hallway towards me. Her hair was all up and falling, beautiful, she was wearing multiple layers on top, and she was wearing flannel pajama bottoms, with a tutu over the flannel pajama bottoms. And I just thought how incredibly beautiful she was and how happy I was that she was free enough in her spirit to dress like that. I forgot she was wearing her UGG boots. So, she had her flannel pajama bottoms, which I think were a Christmas pattern, tucked inside her UGG boots, so she was like a vision. And she used to call me and say, “Mama, do you want to hear a poem I just wrote?” As if I would ever say no. And then she would read me, she would read me this poem, and I’d end up just feeling jealous because she had this—she was a wordsmith. She had this wonderful way of choosing the right word, and I’d have tears dripping off my chin. Her stuff was very moving. I’m a poet, and I just would feel jealous because I’d think, “Oh, that’s such a good—I wish I had said that.” And she was my biggest fan, and I was hers. We had a rough time when she got involved with someone who was very abusive to her, very much like her father was with me, and she was madly in love with him. I watched her give up her life for this guy, and I felt like I could tear him limb from limb. I was so angry at him, and I knew what her future would hold if she stayed with him, but I could not speak to that because I had lived my life. But it hits… I kind of had a near-death thing happen once. I was driving my car down the road, and I hear a crash. I look up, and here’s this car coming straight for me from across the way. The guy had run into a post and bounced off, and he was coming across right towards me. He would’ve hit me right at my door. I managed to pull off the road, and he missed me, but I sat there, and I thought—I was just aware of how quickly that happened. And when I told her about it, it’s so funny to think of that, because what happened to her then was she realized that my life, our lives, could be taken. I could be taken from her. And she called me and said that she had this epiphany. We always called each other with our epiphanies. And she said, “I have this epiphany, Mom, that before, way before you were a mother, my mother, you were a woman. And you walked on the beach, and you danced, and you laughed, and you deserve my respect.” And at that moment, there was this shift in our relationship. I continued to be your mother and continued to offer suggestions for how she should live her life. And where before she would be resistant and butt heads or whatever, she would say, “I hear you, Mom, and I know you’re telling me that because you love me.” And that’s what I lost. I was really super proud of her. She managed to break away from the fellow, and she and her friend Kelsey— they were sister friends. They both called themselves soulmates. They decided one day, and they worked together and had different restaurant jobs. When she went to California, she was 22, and Kelsey was 20. She was 24 when she was killed. I was so proud of her for having the courage to go. And I felt like that so many times in our lives together. There was a point in time when I knew that if I held on, I would lose her. And if I didn’t get on board with her, the quality of our relationship would change. And more than anything, I wanted to have a relationship with my daughter. So, I did the best that I could inside, with all the fears that I had about them going and what they were going to do. She and Kelsey and her brother Josh—I’ll show you a picture of Josh. They went out to California. They decided they wanted to live in Pacific Beach. They went to California, and they found an apartment, and they both found jobs. And that’s Joshie. This is my favorite picture of them. And they probably are smoking pot. I mean, I’m pretty sure they are. They loved music. They were best friends. This is the last time we saw her alive. It was Thanksgiving 2008. She dyed her hair black. And when I saw her, because I had all these pictures of her, she used to have auburn hair. She always did that red color that’s so gorgeous. And so we have lots of her hair. Do you want to hear a poem she wrote?

Diane: I do.

Elle: This was in 2006. It’s like ripping away warmth on a cold night. It never gets any easier to watch them leave me standing at the gate. My love comes pouring out, reminding me where my center really is with my family. I miss them so much already it hurts. And I can’t keep the tears from pouring out. I try to be strong, but the second I think of them, my eyes burn and my soul starts to ache.

Diane: Oh, Elle, that’s something you could write about her today.

Elle: I want to hold my mama’s face. See my brother smile and give Daddy another hug. I feel so blessed to love their company so much but cursed at the same time to be a gypsy at heart. I love to travel, and I’m truly happy in California, but leaving Josh, Dad, and Mom, Grammy, and Nikki never gets easier. And I doubt if I’ll ever be any better at saying goodbye. And so I started thinking of goals for myself. I want to go to Europe when I’m 25. That gives me two years to plan and save. Coming to California gave me the confidence to strive for more. I’ll get a job and start a fund. I’m going to Europe. And she did.

Diane: Oh gosh.

Elle: There was depth in our relationship.

Diane: What do you mean?

Elle: It wasn’t a surface thing. There was a soul thing. A love of music, a love of the written word, a love of art. A love of sunrises and sunsets and the ocean and poetry. And we, the three of us, my son and daughter and myself, we walked through fire together. Their father was abusive, and he didn’t know any other way. It was how he was raised. He tried really hard. The first time we went to California, I ran away from home with him. Emily was two, and Josh was eight. And we got one-way tickets and told their dad that we were going on a two-week vacation, knowing that we weren’t coming back.

Diane: Wow, that’s heavy.

Elle: I wasn’t a perfect mom, but I was good enough.

Diane: You’re doing your best, right?

Elle: And I wish that I could have wished for horse beggars. We rode, but there are things that I wish that I could have saved them from, but she was a grace to me. She was.

Diane: Oh my gosh. You just had me in tears for a long time now.

Elle: I think that affects people. It’s a gift I have. We joke about it because when I go inside and tell the story, I see all these great big men with their heads down like this and wiping tears away. And the first couple of times I felt that, and then I realized that it’s a good thing to be able to tell a story that moves someone from their head to their heart. That’s a long distance, and to have a story—and tell a story that helps people feel is not a bad thing.

Diane: And it’s a feat inside the prison where they’re guarded, right? They don’t have that opportunity ever. They’re never alone. The majority that I’ve met have never really been taught how to share those emotions. And to hear it from someone especially like you has been… I don’t know what I would even call you, I don’t know what the terminology is, but the victim or just someone on the other side of destructive behavior. So, I give them the opportunity to let go and let their hair down and just cry. They want to cry for whatever that is. That’s beautiful.

Elle: You can never be prepared for something like this, I don’t think. Although I talked to her on Thursday night, it would have been the 5th of February, she called and we watched the movie Into the Wild, about Chris McCandless. We watched the movie together. We read the book and my book club had just had our meeting about the book, and she was calling to see what the women’s reactions were. A lot of people, women, several of the women didn’t understand and thought it was really a bad thing that he did, and so we talked about that and how it’s just such a good conversation. Never, never imagining it would be my last conversation with her. We were getting ready to hang up and she said, “Oh, Mom, I had a dream last night. Can I tell you about it?” And I said, “Sure.” She said, “I dreamt I was outside my body looking down.” And of course, the first thing I thought of is that it happens when your soul leaves your body. So I had a moment. I mean, I couldn’t say that to her. How could I say that to her? I could hardly acknowledge it myself. So I said, “A lot of times, dreams are not about the obvious thing. Think about if there is a dream that you have that you’re not pursuing or something that you want to do.” And that’s how the conversation ended. And then it was Thursday, Sunday night. Her soul was outside of her body. And she came to me. I got the call at about 10:30, and it was Kelsey’s mom who said, “There’s been an accident. You need to call this number.” And it was Scripps, La Jolla. They said, “She’s on a ventilator, and you need to get here as fast as you can.” And I asked them, “Please don’t let her be by herself. Tell her I’m on my way, but don’t let her be by herself. Please.” And so then I called my brother and my son and friends of mine. I had a job that I had to have coverage for, so I had to have people come over and get access to my files and a lot of stuff like that. And so I’m in my room and I’m getting ready, and all of a sudden, she’s just there. I know she’s there. I’ll put my hands on my heart and close my eyes, and I just say to her, “I’m on my way. I’m on my way, and if you can wait for me, but if you can’t, know that my love is with you wherever you go, forever.” And she said, I didn’t hear audible words, and in my heart and my soul, I heard her say, “It’s okay, mama. It’s okay.” And then she was gone. I didn’t make the connection then that meant that she was gone. Because I couldn’t make that connection yet. So my background is in speech and language pathology, and I had studied traumatic brain injuries and what you have to do to help people regain their language, and so I had all these plans. I called Kelsey and I said, “Surround her with everything that she loves—her blanket, her stuffed animals, put pictures on the wall, have music, because those things are important.” Her death was… I call it the line of demarcation in my life. So there’s the time before Emily died, and then there’s the time after Emily died. And everything shifted, everything changed in that moment. I get lost sometimes in the story.

Diane: So not that you want to replay the stay in your head, but I would like to venture into that a little bit and then obviously get into your relationship with Alan, who’s now in prison, and what that has turned into for you. If you want to tell us what happened that day?

Elle: When I got to the hospital, in the corridor outside the ICU, there were probably 12, or 15 young people standing in little clumps up and down the hallway. I didn’t know who they were, I just noticed them, and then went in the door and, you know, went around a corner and saw her in the bed. Realized that up until that moment, I had been entertaining the idea that she was still there, and immediately when I saw her I knew that she was gone.

Diane: How did she get hit?

Elle: She was in a crosswalk. Here’s the thing, her friend Kelsey told me later that Emily had told her that it was the most beautiful day ever. And it’s a line from the radio. They were like tall Radiohead junkies. They loved Radiohead. There’s a line in one of their songs about no matter what happens, today has been the best day ever. And Emily told Kelsey that. And it was just a day where she got up with her, got up and had breakfast, and then went with one of her co-workers, Babs, to get a cat. And so she went and got a cat, and she worked for a little while. And then she and her friends sat on the wall on the beach watching the sunset, and she had a beer. I don’t know if she had a beer because at that time she was out, she had migraines sometimes when she drank, so she wasn’t drinking. So she was ready for bed, and her friend Kat talked about it all the time when she called me. Emily just adopted Kat, she loved Kat, and Kat called and said, “Come and have dinner with me.” So Emily got dressed and went to Starbucks and had dinner with Kat. And when she was walking home, she was in the crosswalk, walking. Alan and his friend had been in this bar, diagonally across from the Starbucks. He was homeless when this happened. He and his buddy. I had just gotten to Pacific Beach two days before. They worked a day job and got paid, and they took the money and bought beer. And instead of finding a place to live, they were at a campsite and they shared a 12-pack and then they had three pitchers of beer at the bar. And his friend had him drive the truck, and he didn’t see her. She was in the crosswalk, and he didn’t see her, and he hit her and threw her 16 feet through the air. And she died of blunt force trauma in the street in front of the Starbucks. And I was in Florida, it was 10:30, and I was thinking I should call her, and then I thought, no, I was really tired. I will call her the next day. And for a long time, I had so much regret because I thought, well, if I called her, she would just have stayed sitting there, and maybe she would have told me about this big red Dodge truck that roared by. But then the other thing was, if I called her, the timing would have been as the accident was happening, and I might have heard it, which is not something I would have been able to live with. So the people, the fire department who came, was the one down the street that she used to take coffee to every once in a while. She would tell me that her big thing for the day, her kindness for the day, was taking coffee to the firemen down the street. And then there was Kat, who thought it was her fault, and who for years lived with this guilt and shame about what she’d done to her friend, and Kelsey, who was expecting Emily any minute, and then she didn’t come home, and doesn’t answer her phone, and Kelsey finally gets dressed and goes out and finds her best friend’s mystery, and who for years afterward, every time she would try and call someone that she loved, and they didn’t call her back, would have horrible panic attacks, and have to call her mom, and her mom would have to talk to her until she got a hold of herself. I still have this thing. Just the other day, it happened. I couldn’t get a hold of my son. He was shopping and didn’t have reception, but I didn’t know that. So that weird thing is happening where it sounds like somebody’s on the line, but they’re not there. And I’m starting to get really nervous when I say something like, “Oh, no.” And he called me a few minutes later, and he said, “Mom, why, why are you so upset? I was just in public shopping.” And I realize I’m still going to that place.

Diane: Gosh, I’m speechless.

Elle: Once you know something, not just the rug, but the world was pulled out from underneath me. I realized I like living in bubbles. And we think we’re protected, and we think everything is fine, but nothing like that will ever happen to us. And we’re not protected. Bad things happen. Her dad said to me, he wasn’t asking why it happened to him, because he thought, why shouldn’t it happen to us? It happens to everybody. It happens to other people. Why shouldn’t it be us? What makes us different? What makes us special is that we think we’ll be protected. And so you learn how to carry it. I just learned how to carry it. It doesn’t go away. It doesn’t change. But you learn how to carry it with grace, you learn how to carry it so that you can move through the world, have a life, and be used to love people. The worst thing that happened to me in my life has ended up bringing the most life.

Diane: It’s amazing how you’ve channeled something. Literally, like you said, the worst thing that can happen in your life turned into something so positive and beautiful. I’ve had the opportunity to talk and sit with Helen, and you use that word “angel,” and he uses that too. The thousands of people you’ve touched, the talks you’ve given, and the hope you instill is just gorgeous in so many ways. Born from so much hurt, so I just look up to you.

Elle: I’m nobody special. I just know that if I could do it, anybody can do it. Now, at first, I found myself— the rage was frightening. The anger I felt, I watched myself losing control. I actually lost control in the grocery store buying pumpkin seeds, and I yelled at this little old lady. I didn’t have a lot of money, and I only had enough money for pumpkin seeds at half price. I told her they were half price, but she rang them up full price, and I just went berserk. I watched myself, the whole time having this observer part of me that was unemotional, watching things happen. That was very helpful during the time we were in the hospital with her. I knew what I was doing, and I watched her shrink, like her head was down. I couldn’t stop, and I didn’t want to stop. Finally, the manager came, and I started to calm down a little bit. But I got my bag of pumpkin seeds at the price I wanted to pay, and I got in the car, and I couldn’t find out what it’s like to be on the receiving end of that rage. I did not want to do that to anybody.

Diane: And how long was she gone at that point?

Elle: About a year and a half.

Diane: Oh my gosh.

Elle: The first year, we were back and forth to California. Every time he was in court, we were in court. Me, Josh, and all of her friends. We filled up the courtroom. When we were there, we were all together. Most of them worked for Starbucks, so they’d get together and work up their schedules so that everyone could be at something at some time. You could be at the trial from 9 to 12, and then it was just amazing how they did it. Then we’d have barbecues and music, and we went to Balboa State Park, did all this stuff. And then there was the last thing: the sentencing, I think that was in October. And when I went home, there was no more. It was like it was over, and that’s when the bottom just fell out of everything. That’s when it got really dark.

Diane: So your reason for being at these seven events was to make sure that he was convicted and sent to prison?

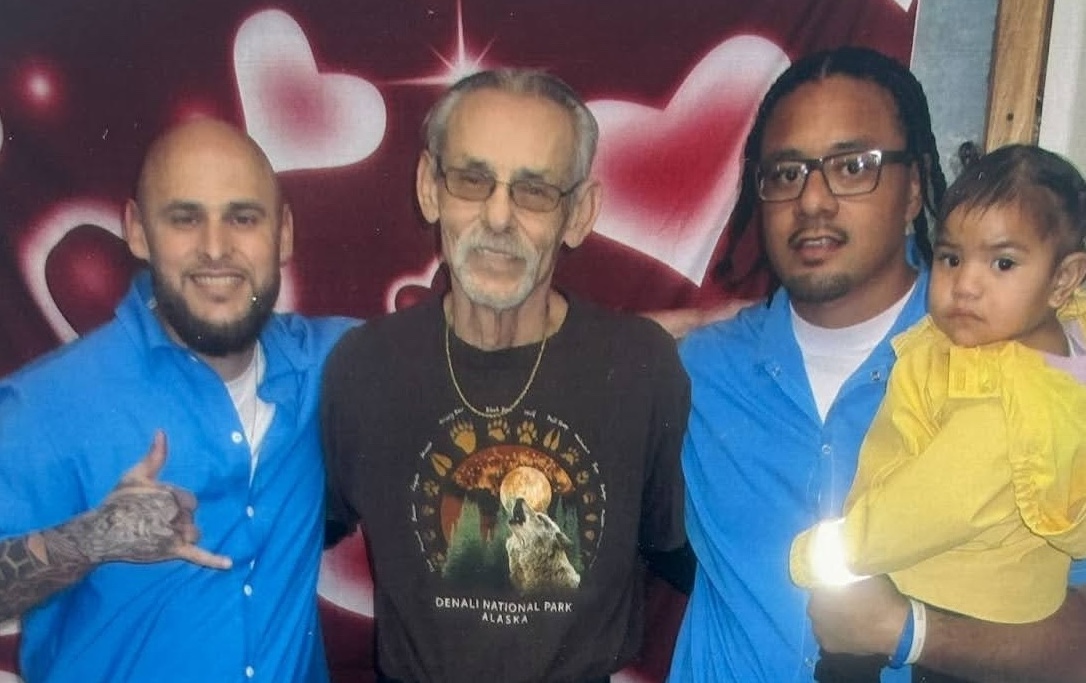

Elle: My reason for being there was to represent Emily. People in Florida said, “You don’t have to go, you don’t have to go,” and I’m like, “How can I not go? That’s my daughter. How can I not go?” Here’s the deal, Diane: My family is full of alcoholics. I was raised in that environment. My father was an alcoholic. He worked at a brewery in Indiana and came home drunk every day when I was a baby. The first nine years of my life, he was drunk every day, sometimes passing out. All my uncles were alcoholics. There are pictures of my father’s family. He was one of 13 siblings, and all my uncles have big beer bellies. They all drank. Two of my uncles drank themselves to death, one of them sitting at the kitchen table. My brothers were alcoholics too. So I know about alcoholism, and when I heard that it was a drunk driver who hit her, I knew things about him before I even knew his name. You don’t drink to that extent—it was his seventh DUI and his third felony—and you don’t drink that way unless you have unmanageable pain. I knew this about him. I remember the first time hanging up the phone and realizing, and I thought to myself, “Someday I’m going to have to have a conversation with this guy.” So where I am now comes from that conversation with him, which took place almost 10 years after Emily died. Until then, how I felt about him was that I didn’t say his name. If I talked about what happened, I’d say “the man who took Emily’s life,” “the man responsible for Emily’s death.” I decided the year after he was sentenced that I wouldn’t give him any more of me, so I didn’t think about him or say his name. But always, in the back of my mind, I wanted to have this conversation with him because I wanted to understand who he was and what happened in his life. That was really important to me. And of course, it wasn’t possible, and it happened when it was supposed to happen. I had taken care of my mom for the last three years of her life, and then I came to Gilroy, California, to stay the summer with my nephew and be a nanny for my niece. I decided that now was a good time to have that conversation. So I called CDCR and got put in touch with the HMSA, who then connected me with Martina, and we started the process of arranging the conversation. They had to interview him first to see if he was a candidate for a victim-offender dialogue because not everyone is. So they were going to go the next day to interview him. I woke up in the middle of the night, thinking about it, and I thought, “If he has the courage to face me, to sit across the table from me and have a conversation, that shows a lot of courage. And it says more about who he is than what he did.” Just in thinking that, he became a human being to me. Of course, when he was interviewed, he said, “I’ve been waiting for this,” and Martina said he just broke down and cried. So then, my whole perspective of him changed. I was talking to a friend, and she finally asked me, “Who’s Alan?” and I said, “He’s the man who killed Emily,” and she said, “I’ve never heard you say his name before.” There was this shift, and I think we all have to make that shift, where they go from monster to human being. It was amazing how quickly it happened. So we worked together, wrote letters back and forth, and then I went to San Quentin on January 15, 2019. We had all these plans, agendas, and goals. But he was an hour late, and I stood there thinking, “I can’t remember anything. I have nothing. I don’t know what I’m going to do.” My support person said, “You’ll be okay. Just trust the process. Everything’s going to be fine.” Then Martina came around the door and said, “He’s here. Are you ready?” And I said, “Yes.” We stood up, and everyone backed away from me. Then he came through the door, and here was this man. He was small in stature, hunched over, his head down, looking scared and disheveled. His face was gray; he looked like a prisoner. The only thing I had in my mind was, “I have a hug for you, do you want it?” which I say to people. And he said, “Yes, ma’am, I do.” He stepped towards me, and I stepped towards him. I embraced him, and he cried on my shoulder. I cried with him, comforted him, and held him. He sat down and said, “Don’t you want to hit me?” I said, “Nope, I don’t.” He said, “I can’t really wrap my mind around this.” And I said, “I can’t either, but how about if we just go with it? Let’s just go with it and say yes.” And so we had the conversation. One of the things I wanted from him, two things, was for him to look at these pictures and to tell me about his childhood. I also wanted it to be light-hearted. I don’t even know where that came from, but it was light-hearted. I wanted there to be laughter because that’s important. And there was laughter. I say all this because I want you to know the process and the journey we went through—it’s significant. When he told me his story, he had written a timeline for the GRIP program, and he went over it with me. I was learning about him, and the focus of victim-offender dialogues is always on the victim: what the victim wants, what the victim needs. But while he was telling me, I felt a shift. It wasn’t so much about me anymore; it was about him. His childhood was tragic, and it made so much sense that he would be drinking and doing what he did. It’s not an excuse, and I don’t excuse his behavior, but I think any of us, if we had lived through what he lived through, would have significant difficulties. During the five hours we were together, I saw a change in him. His countenance shifted. There was a light in his face. His cheeks were rosy, his eyes were sparkling, his stature was different. He was funny. I don’t know if you saw that side of him, but he’s a funny guy. It was like watching love work, love doing its work right before our eyes. It was incredible. In the end, the last few minutes, Martina said, “We need to decide how to go forward,” and Alan must have planned for that because he had a little piece of paper. I had a picture for him of me and Emily, but I couldn’t give it to him. I had to send it later. But he had written his address on a piece of paper, which he wasn’t allowed to do, but he kind of quickly slipped it over to me. We decided to correspond, and somehow I got put on his visitor’s list, which is totally against the rules—a bit of a miracle. So we spent time together, now and then. I consider him a friend. I don’t know what the parameters of our relationship will be now because I’m still Emily’s mom. I don’t know how much I can be a part of his life or what that will look like. Sometimes, he and his mom are like, “What you did for him.” But I always tell him, “Alan did the work. I may have spoken up for him, but Alan has done the work.” So don’t say that anybody saved Alan—he saved himself. And that’s so important because I refuse to take that designation. Whatever that is—I don’t know if that makes sense.

Diane: It does. I see you as you came to him, and it’s amazing. Use that word when meeting someone for the first time who has given you something you’ll never get over, like death. And here you say that there’s this love that unfolded between us. I talked to him about that and told him that he had to go to the darkest place he’d ever been, and he had to choose to dismantle all those experiences that happened to him. There aren’t many people in this life who do that. I’ve spoken to a lot of people in prison, but many just can’t, and they don’t have the resources to. Especially out here, with men, they’re taught to go there. The people who raised you, who you had that innate love for, you have to turn on them, look at that, and grow from love within that. So you’re right; he did that hard work, but you came to him with love and forgiveness, showing him that there’s a light to a better path, which has to be the steam and the engine for him.

Elle: I’m proud of them because he could have chosen the other way.

Diane: Especially since you’ve seen the other side of people who don’t go to prison or potentially never address what that hurt or addiction is in their life. You’ve seen lives continue without doing what he’s done. Tell me about the pictures and sharing them with him of Emily in the hospital.

Elle: Let me tell you about one point. Well, he is a priest, a real spiritual guy. We had had a lot of conversations about death and the meaning of death. As I mentioned, he and his wife’s Airbnb was where I had the conversation. They said, “So, you two have been talking about Emily. What do you think about talking to her?” Because, of course, she was there. Alan said, “You go first,” and we had a laugh about that. I had my hand on the table and just bowed my head. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I remember the moment. Alan reached across the table and took my hand, which he wasn’t supposed to do. But he did. It was just so sweet. I don’t remember exactly what he said to Emily, but then it was time to show the pictures. He was crying, and Kathleen was comforting him. Noel got up and walked around, putting his arm around his back. I just started with the pictures, telling the stories behind them. He was sobbing, and I think that was the hardest thing. It was probably easier for him to talk about the abuse he suffered than to see the pictures. He said something like he hated that those pictures would be in his mind forever. I said, “This is part of it. You have to let go of that. Let it be what it is now. It happened then, but this is now.” I suspect that when he told me, I’ve been working with him on his parole, and I spoke at the parole board hearing and his end bank hearing. I’ve written multiple letters to the governor. It’s very emotionally taxing. But I love doing it because it keeps her real. It’s why I love going inside, showing these pictures, and talking about her. Sometimes the guys remember her and talk about her, and they call her M. Someone at Mule Creek wrote on the whiteboard, “In loving remembrance of Emily.”

Diane: Oh my gosh, I’m moving to Oak Creek State Prison in California because of what you do. People don’t do that. People are afraid. I have a lot of people look at me like, “Why do you go in there?” They’re afraid my house, my things, will get stolen, or that something will happen to me, like bodily injury. People are so consumed with fear that someone like me, who’s giving a service and teaching and interviewing and humanizing, but someone like you actually goes to the heart of why they’re there, and they can feel you. As I often say, I haven’t met anyone in prison who wasn’t a victim first. They’re you, embodied in a lot of different aspects. I’ve even talked to one of the guys on our team, our office admin inside, who knows you and your daughter. It’s amazing. It’s amazing that you’re willing to do that.

Elle: It is my honor to do it. There’s not a molecule in my body that’s not more than willing. Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night, and I think about what I do, I remember some of the faces and the stories, and I’m so filled with gratitude that I feel like I could float right up through the roof.

Diane: People think we’re crazy for that, and I feel the same way. I feel, and I don’t feel like I can say it to many people, but I’m honored to be able to walk into San Quentin. I know, but people don’t understand that you and I are not the norm.

Elle: Would you have it any other way?

Diane: No, I live my life to go into prisons around the world, hear their voices, see them, sit with them, feed the fire, and talk and listen. People always ask, “Well, Diane, how can you take that negativity and that burden?” But for me, it’s a gift that they’re able to sit there with me and share. The world already knows how bad they are, and yet they’re willing to sit there, be vulnerable, and tell me what happened to them. It’s a gift that they open that door for me. But people need to hear it from your side. You have a special situation where, I don’t know how you feel about the word “victim.”

Elle: I’m kind of a mother of a victim and, in a sense, a survivor. A survivor of grief. I survived loss, but I like “healing partner” best of all. That pretty much defines who I am, who I am now at this point in my life—a healing partner. I partner with them. The first time I went to Soledad… So my conversation with Alan was in January of 2019, and then I got to go to his GRIP graduation.

Diane: You surprised him.

Elle: I know, it was amazing. I see him crawling over people, holding onto his cap because he’s wearing a cap and gown. He’s crawling over people to get to me. I had just spoken to the warden, and I said, “So, what about hugs? Because that’s my big thing.” She put her hand down by her belly button and did a little shake, like, “Only where nothing.” So I said, “Okay,” and turned around, and here he comes toward me. He throws his arms around me and gives me a big hug. I whispered in his ear, “Alan, you’re not supposed to be doing this. You could get in trouble.” And he looked me in the face and said, “What are they going to do? Put me in prison?” That was my first time being on the inside with the guys. They asked me to speak, and I was the first survivor—or kind of victim—who’d been asked to do that. I stood at the podium, looking at 140 guys in caps and gowns, all in rows, and I thought, “There is no place on the face of this earth I’d rather be than right here with a couple of pictures of Emily.” It was amazing, and I just fell in love with them. I told them, “You guys look way cooler in your caps and gowns than you do in that blue,” and we just laughed. Oh my god, what a time that was. He was sitting off behind me to one side, and I kept turning, because for me, this is a triumph. But for him, this is what he did. I kept looking at him, and Jacques, the guy who started GRIP, was standing behind me. He had his hand on my back as support while I was sharing, and he motioned for Alan to come and stand with me. So, Alan and I stood at the podium together. I told them that something changed in me after, during, and leading up to the VOD. I became the person I had always dreamt of being. I was bold. I told Martina I wanted to give Alan his honor cord, and she said, “Well, let’s find out how you can do that.” Somebody came over to me and said, “Well, I guess you can do it. We’ll just stand here.” And so, I was able to give him his honor cord for graduating from the GRIP program. I’ll show you that picture.

Diane: Oh my gosh. Are you in the chapel or in the visiting room?

Elle: The little room where we had our VOD was, we went through that into the little room. So, they let me give him his honor cord, and the guys were like, “Oh!” I’m funny. I crack jokes. Sometimes I say “fuck,” which really makes them laugh, which I love. When they laugh and I say “fuck,” they don’t believe a little gray-haired white lady says “fuck,” but I do. That’s one of my favorite words. And they don’t apologize anymore, because my mom is dead and she doesn’t know, so…

Diane: You can’t let your hair down in there. People don’t understand that their social distance was long before COVID ever hit, and they have us pretty much on a pedestal because they can do things to us that will put them in the hole or solitary confinement. So there’s already, I don’t know what you’d call it, but just this aura of them being on their best behavior. So, when someone like you comes in and is real and free with yourself and using those words, it’s like, yes, I’m here. It’s real. So, it’s definitely cathartic.

Elle: I love it. When I went to Soledad, I didn’t know what to expect—victim impact panel. So, when I have my book, this is what I use for my victim impact statement from the sentencing part of the trial. This is what I showed the jury and the judge, and I’ve just added to it. And since then, I’ve been going to a victim impact panel. I’m not sure I want to tell a story, but they talk about not hugging, and you know, they didn’t really tell me a lot of rules. So, I walk into this room and I’m not afraid at all, probably because I’ve already been to San Quentin twice, and both times were beautiful, so I don’t have any fear about it. But I walk in, and there are these guys, 19 of them in a circle, and I see their faces when I walk in. They just look so happy to see me. I just put my hand out and walk around the circle and touch palms, not thinking anything about it. Then I think, Martina probably said not to do stuff like that. So, they go around the circle, and they introduce themselves by saying their name, the name of their victim, and how many years they were sentenced. When all their sentences are added up, it comes to like 800 years or something. A huge amount of time. They say that I just feel this love for them, this compassion for them. When I show the pictures and tell them about Emily, they’re crying. I’m not used to men crying. I said, “I gotta tell you guys, I’m not used to men crying. Your tears are precious to me. I’ll take your tears with me.” And I do. I’m talking about me being on the ventilator, and I’m showing those pictures. This young Vietnamese man leans out of the circle and says, “I hear you say the words ‘love wins,’ but when I look at the picture of Emily on the ventilator, it reminds me of my victim who was on a ventilator.” He turns to me, and the anguish on his face is palpable. You can feel it emanating from him. He says, “Can you help me?” And I’m stunned. In that moment, I think, “What do I have to give him? What can I say?” I have a hug for you if you want it, and he stands up. I walk over to him, and I just hold him. I hold him, and he’s sobbing into my shoulder. I don’t remember what I said, I never remember what I say, except that “you’re loved.” But I see him as he was before whatever happened to him happened. The little boy that was full of life. I wipe his tears away and hold his face in my hands and tell him how loved he is. It’s just this transcendent moment. If nothing ever happened to me again other than that moment, it would have been enough. So then, I go and I hug all these guys in this line. I do the same thing. I get to hold their faces and tell them how loved they are. I see them as they were when they were little boys. It’s a gift. I feel like I carry the spirit of the great good mother with me. And she is so fucking real, it’s not even funny. We, all of us, are loved. There is, yeah, it’s real. And he slips me a note at graduation and says, “My mother’s been dead for a long time, and when you talked to me, I heard you in the voice of my mother.” When he got out, he called me, and we stayed in touch for a little while. He called me Miss Elle. They always call me Miss Elle or Mama Bear. And they always talk about how much they get from me coming, and I always try to tell them, “I get as much as you get from being here with you.” Diane: They’ve been cast away. Our society has cast them away and put them in a 9-by-4-foot cell, at least in the U.S. I’m pretty close to that. I feel it’s smaller. They’re treated like hell. And they already have all that guilt, shame, remorse, and trauma on their shoulders. That’s beautiful work you do.

Elle: I love them so much.

Diane: Because they’re not seen as humans. Yes, they intentionally did or didn’t do what they did, and they need to pay the price for that. The institutions need to keep popping up so we can put them there.

Elle: Here’s the thing about that. One thing I realized: nothing they could have done to Alan—whether it was the death sentence, hanging, firing squad, or whatever—nothing would bring Emily back for even one second. All I was left with was the question I asked myself: Who do you want to be? How do you want to show up in this? Nothing’s going to bring her back. It doesn’t matter what his sentence is. I wanted him off the streets so he couldn’t hurt anyone else. That was my thing—make sure he can’t do this, whatever that means. I wasn’t happy or sad about the sentence he got, but nothing would bring her back. So, the question was: Who do I want to be? How do I want to show up in the world? I made a choice. I woke up in the middle of the night, the first night I was in Pacific Beach, in a hotel room. I woke up and sat up in the bed, saying out loud, “I choose life. I choose life. I choose life.” Over and over again. Looking back, it’s like something in my spirit knew this was a crossroads. For whatever it meant at that moment, I set my course by saying that, and it’s taken all these years to flesh itself out. But I’m glad I chose life.

Diane: And you’re doing beautiful work because of it. You’re impacting so many people with your beautiful healing journey. It’s amazing. So, I’m on the same path as you. I want to get in there and hear those voices, to share them. Demystify and humanize—it’s a lot. I’m the same way as you are. We have to write the stories. We have to share them with the world. You’re learning this. We have to learn it with you. And it’s like, “I was just there. What do you want to know?”

Elle: I feel like we’re kindred spirits.

Diane: Well, I’m absolutely moved by everything you’ve shared today. Healing comes to me after I’ve been speaking with you. I think about the word love. I think about your forgiveness. I picture you with those men inside prison, hugging them, holding their faces. I think of all the sympathy and compassion you have for Alan, where he’s been and where he is today. So, I just want to thank you for the gift of healing that you’ve given to me and everybody listening. I’m in awe of what you’ve done. Thank you so much for giving your time.

Elle: Well, Diane, it’s been wonderful to spend this time with you. I love sharing our stories. I love talking about love and how it wins. In so many ways, I am so grateful for the work that I’ve been given to do. Emily’s death continues to nourish me, and it continues to nourish many others, and I’m grateful. Thank you for this time. You’re a joy.

Diane: As we close, what resonates most deeply with me is Elle’s extraordinary compassion. Growing up with an alcoholic father, she showed an innate curiosity about his trauma, seeking to understand rather than judge. From the very beginning, her heart was open. That same curiosity and compassion, to me, has become the foundation of her life’s work. Elle’s story is one of transformation, resilience, and profound forgiveness. In her raw and vulnerable moments with Alan, her compassion tore down walls, allowing both of them to confront their deepest fears and truths. Her work within prison walls is far more than storytelling. It’s about forging connections, fostering healing, and providing every individual with their own inherent self-worth.

I can relate to Elle’s love for the people she meets inside, and it shines through. It shows that compassion, when paired with action, can bridge even the widest divides. In finding this purpose, Elle has become a partner in healing, giving as much as she receives. Her choice to embrace life, despite immense grief, is a testament to the boundless strength of the human spirit: its ability to grow, understand, and find peace—even in the most challenging circumstances.

Thank you for joining us today. Be sure to tune in next week for an extraordinary episode of the Prison Podcast. We’ll be speaking with Alan, the man responsible for the death of Elle’s daughter, Emily. Alan courageously participated in a victim-offender dialogue with Elle, sharing his perspective on rehabilitation, his journey to sobriety, and his efforts to seek forgiveness while healing from his own trauma. Now incarcerated at San Quentin, Alan’s story is one of accountability, redemption, and the complexities of finding humanity, even in the darkest moments. You won’t want to miss this deeply moving conversation.

See you next week. Meanwhile, be kind to yourself.