Growing up in a house dictated by an abusive alcoholic, I didn’t know love as anything besides the absence of hate.

My family is a casualty of McCarthyism after the Korean War. My biological dad was accused of colluding with the enemy as a prisoner of war, arrested, and incarcerated. I have three siblings: Donna, five years older than me; Jimmy, four years my senior; and Paul, one year my junior. My mother first got pregnant at fourteen, and told me she didn’t even know how women got pregnant until a doctor told her. Her parents, uneducated and poor, didn’t discuss such matters. That habit carried over to my generation.

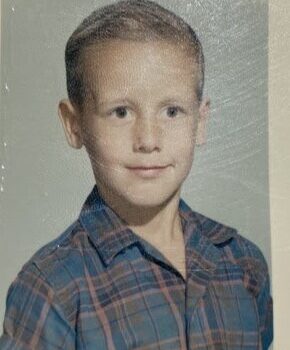

When I was three, my mom met my stepdad. I don’t know where they met or what their interests were. My first memory is of living in a big old house in a small town. My step dad worked on the surrounding farms, irrigating the fields with siphoning pipes. Alcoholism was in our house from early on: he and my mother would go to bars and usually end up fighting. I remember the fleshy smack of him hitting her. I wet the bed and had a speech impediment that wasn’t resolved, with a simple cut of the connective tissue under my tongue, until I was in first or second grade.

As a young boy, I don’t remember love even existing in our house. Growing up in a house dictated by an abusive alcoholic, I didn’t know love as anything besides the absence of hate. You either loved or hated, feared or didn’t. Mom had dinner ready for my stepdad, had his drink made, took off his boots and socks and rubbed lotion on his feet; she made sure we knew to be quiet or leave the room, that we didn’t do anything to make him mad. So I thought love was not hurting someone. Being in someone’s presence and not being afraid. Love wasn’t something we talked about. “I love you” were just words that meant everything was okay for now.

But I knew something was missing. There was something Mom was giving my stepdad, a nearness of bodies, that I wasn’t getting. I sought out that physical expression, even if I didn’t grasp the essence of what it meant. Even my first sexual encounters were by the numbers: first base, second base, third base. Is it the same for everyone? I thought so. Fortunately for me, my “first time” was with a fifteen-year-old French girl. I was thirteen, but lied and said I was fourteen. I’m glad I lied. She taught me to slow down and notice things. She placed my fingertips on her neck so I could feel her pulse. She made me keep my tongue in my own mouth—so much for French kissing! She taught me that the nearness of bodies could be one of trust and discovery.

That experience with Evonna showed me that there was an equality to a sexual union between girls and boys, not the subjugation and dominance I had seen growing up. I felt she had revealed a secret to me, though it was more of a sense than a knowing. Looking back now, the respect she showed me, and the respect I was responsible for showing her, was as close to love as I had experienced at that point. So I equated sex with love. I wanted to be loved a lot! This was the summer before high school. My second week of freshman year, I was expelled for smoking marijuana with another student. I was called into the dean’s office, where two sheriffs were waiting. The dean told me the kid I had smoked with was acting bizarre in class and had given me up. I asked if I was going to be arrested; he replied, “No, you’re going to be expelled.”

I was used to maximum punishment for small infractions at home. All I could think was that my stepdad was there and would see me coming back in a cop car, and that as soon as the sheriffs left he would beat the shit out of me again. I asked the dean if the cops were going to take me home. “No,” he said, “you can walk yourself home.” I was more relieved than he could know. He shrugged and filled out a form, ripped off the yellow copy and gave it to me, and said I could go. The closer I got to home, the more frightened I became. I started folding the paper into smaller and smaller squares. I was tired of being beaten by my stepdad. He’d been beating me with his fists for almost ten years. Just for ten seconds or so each time, but he’d hit my ribs and my back—even my butt, because I’d instantly curl into a ball and wait for it to end.

I came to a telephone pole a few feet from our house and stuffed the paper into a crack. I stuffed it in as far as I could. Then I looked at the house and realized there was no love in it. I kept walking and never returned.

I hitchhiked from California to Vernal, Utah to see my cousin Roy. He’d know what I should do. He was always good to me; he was fun to be around and his whole family was cool. My Aunt MaryAnn smoked pot and drank RC Cola from the bottle—to get along with her all you had to do was leave her RC alone! No one beat anyone in that house. That was nice.

I got to Vernal with no trouble. My third or fourth day there, we went to an engagement party. A little later I saw Roy getting into a car and I jumped in too; so did the owner of the car and the newly engaged couple, and even Roy’s small dog. Since Roy was the least intoxicated, he was chosen to make the beer run. Thing was, the car only had one headlight on the passenger side. I told everyone we should take a different car. The owner said if I didn’t like it I should get out. I told Roy to pull over; he did and I got out. I begged him to get out too, he begged me to get back in, and I said I couldn’t. He drove off. The very next car picked me up. We saw Roy and them on their way back to the party; I knew it was them because of the one headlight. It was the last time I saw him alive. A head-on collision killed everyone in the car except the owner. I wanted to kill him, but when my aunt took me to his house two weeks later I just stood there and then left. He was a drooling mess. I felt more alone than I’d ever felt in my life. I was still a runaway, now without my cousin Roy. For years I wished he had survived, not me.

I was fourteen. I didn’t return to school for forty years.

I was a mess. I was so completely engulfed in grief that I don’t remember leaving Vernal or arriving in Las Cruces, New Mexico. My aunt Harriet and uncle Joe were too young to look after me, though they did show me a different example of a loving couple: they did not berate me, hit me, or treat me badly. Still, I was lying constantly, ditching school so much I don’t recall going to a single class. I had no friends, male or female. After, I don’t know how long, I was put on a Greyhound bus and sent back to California. Looking back, I think Harriet and Joe loved me. I know I should have treated them better.

On New Year’s Eve 1976 I arrived in Ceres, California, at my aunt Sheila and uncle Jim’s place. My cousin Darren had leukemia and would pass the following April. I knew I wouldn’t be welcome for long, but luckily my uncle Paul and aunt Ramona were visiting. Paul traveled the world working on offshore oil drilling platforms; he offered to take me with them to their next destination on the condition that I go back to school. I said yes with great relief, and I turned sixteen at the Horus House Hotel in Cairo, Egypt! By this time I had learned that females were safer and more fun to be around than males. Ramona, in contrast to my mom, was a fierce defender of her children whether we were right or wrong—a maternal love I hadn’t experienced before. This made me realize that it mattered how I treated people. I still felt apathy for most people, but I learned to treat some with respect. When I told Ramona I loved her, I was saying, “I won’t hurt you, I won’t steal from you, and I will be as honest with you as I can be.” Evonna had taught me a respect for females; Ramona taught me a reciprocal kind of loyalty.

Meanwhile, I still had a deep fear of and resentment toward males. The men in my life had mostly terrorized me; at eight or nine I got lost and, when I went to a house to ask for help, was drugged and raped by a man and a woman. This powerfully distorted my attitude and behavior toward men and women in general, and gay men in particular: for many years I associated homosexuality with pedophilia—I know now that this is ridiculous, but it was how I felt as a young man. (This experience is shared by many men in prison. It’s not spoken of often, because we feel that having been sodomized will make others think we’re gay.) So, for a long time, not being attracted to other males was of the utmost importance in how I represented my masculinity. I did and still do on occasion find some men attractive, but that’s no longer an issue because I understand that beauty can be seen anywhere, in anyone.

For most of my life, then, I would run away from situations I didn’t understand instead of asking for help. Being lost was dangerous, letting someone know you were lost was dangerous, and asking for help was even more dangerous. Period. I have always had this insane reflex to clench my jaw and move on into the unknown instead of admitting that I needed help; when I say I haven’t always recognized when I was loved, it’s because love looked to me a lot like the “help” that hurt me so badly as a child. All of this created a strong sense of entitlement in me, which made it seem acceptable to steal and rob. “This happened to me, so fuck you!”—that was the apathy I felt toward people I didn’t know.

Back to Egypt. We lived in a community called Maúdi, about seven kilometers outside of Cairo. For a while I attended the Cairo American College, a prep school that was out of my league academically, although I did get good grades in creative writing and had an essay, “The Nile,” placed in a ten-year time capsule along with a picture of me that I had developed myself in a darkroom, Aunt Ramona had helped me set up in our flat. I wrote the first draft of the essay sitting on the very top stone of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

In Egypt I had my second sexual experience, with a Nigerian princess—literally. Her family had been exiled there by a military coup, and we met on a school trip to the Cairo Museum of Antiquities. She dropped some papers in the aisle of the bus and we both bent down to pick them up. When our eyes met, I was dumbstruck. She thanked me but I couldn’t speak, so she raised her eyebrows to let me know I was causing a spectacle. Someone changed seats so she and I could sit together. Later we wandered through the museum, amazed at how much time and effort people spent just to have stuff in the afterlife. We agreed that this life should be spent seeking pleasure—which is just what we did later that day in my bedroom when Aunt Ramona walked in. It was an incredible experience, but love had nothing to do with it. (She did tell me I was the best kisser she had ever known: thank you, Evonna!)

Like most teenagers, I was self-centered and had no scruples about breaking agreements. Promises were just a way to get what I wanted. My lack of empathy or regard for consequences resulted in getting a wonderful girl pregnant. I wouldn’t know about it until eight months later, after she moved with her family back to Mississippi and a friend of hers brought me a letter with some adoption forms to fill out. I punished myself for many years after that, vowing never to have children because I hadn’t looked after the one I brought into the world.

Eventually, failing all of my classes besides creative writing, I had to go to work. My uncle told me I wasn’t going to be a bum. I got a Eurail pass and took the train from Geneva to Paris to Brussels to Amsterdam to Frankfurt back to Cairo; by then my uncle had punched some guy in the nose for making a derogatory comment about Texas, and we had to pack up and move back to Ceres, California.

Back to California I turned eighteen and went to work at a Wendy’s. I met a girl my age, and within a week met her stepmom, who was nine years older. What a mess! Margo was a bona fide cougar, a twenty-seven-year-old ex-hooker married to a preacher. She separated from the preacher and swept me off my feet, I moved in with her. Aunt Ramona tried to convince me I was making a mistake, but I cut ties with her and my uncle and cleaved even tighter to Margo. I made her feel good because my youthful vigor was all hers, and she kept me right where she wanted me. Meanwhile, I was doing landscaping work for my crooked uncle Jim, who paid me just enough to stay broke and work for him. I could install an entire sprinkler system, front and back, by myself in twelve hours.

With Margo keeping me in bed and Jim keeping me digging ditches, I finally got the bright idea to join the Army. In 1978 I passed boot camp and advanced individual training and became a military policeman. I figured this way I could provide for Margo and her children, but just before I was to go on patrol she flew to Alabama and convinced me to leave the Army. I did as she wished, regrettably. Her influence on me was supernatural. Why was I so under her spell? Well, she was nurturing and safe, knew how to make me feel manly, and literally screwed my brains out! I still felt a responsibility to provide for her, which was the catalyst that led to my first bank robbery at the age of nineteen.

Unable to find a job in Sacramento, where Margo had moved while I was in the Army, I decided to return to Bakersfield and get a job on the oil field—but a couple of days of job hunting proved that employment was scarcer than I’d hoped. One night, I saw on the evening news that a lone gunman had robbed a bank and made off with an undisclosed amount of money. All they found was a ski mask in the parking lot. Hey! I thought. Fuck yeah, I can do that! I envisioned a sack full of money, Margo happy, the kids happy. Why not?

The first robbery brought me a whopping $570, including $300 in one-dollar bills. That wasn’t enough, so I kept going. Without giving it another thought, I robbed more banks, getting more money each time; finally, I had a few thousand dollars and returned to Margo a few weeks later. We moved to Modesto and I went back to work with Uncle Jim. Since he was a crook, I told him what I’d been doing. What I didn’t know was that he was also on parole. Guess how he got off? A couple of days later, he came to where I was digging a ditch and took me around to the front of the house. I looked around and saw suited men in sunglasses approaching from both sides of the street. FBI. “Don’t run, Mike, you’re surrounded!” I just looked at him. He told me they had my mom’s phone tapped and had heard him talking to her, but that was a lie. He had turned me in in exchange for release from parole. I don’t hold it against him. I turned twenty in federal prison in Englewood, Colorado, serving six years for armed bank robbery.

At twenty-five, I was married after a romantic date, as we were leaving a restaurant where the pianist had played just for us, I said, “Will you marry me?” I hadn’t meant it literally, but Bobbie’s eyes lit up and she said, “Oh yes, yes. I’ll marry you.” Oh shit was all I could think. We were married the next day by a justice of the peace, with his secretaries as our witnesses. I had been released from federal prison a little over a year before. To me, by this point, good sex was love. It was easy to say “I love you” and mean it, and it was easy to hear it and believe it.

At twenty-seven, I robbed another bank. Bobbie and I went on the run with $10,500. We hid out in Beaver Creek, Washington until her cousin gave us up for the reward. When I found out, I decided to turn myself in to save Bobbie from being implicated. The plan was that I’d go to prison and do my time, and she’d join the Army and put together a life for me to parole to. She never visited, and I didn’t think much about her. I never truly fell in love with her, and she never truly loved me: she said later that she married me to get out of a “situation” she was in. I never asked what the situation was.

After two and a half years in an Arizona State Prison, I paroled to her in San Miguel, California. She was stationed at Camp Roberts, one of the first females in satellite communications; she had a secret clearance and was doing well. But she had grown, had become disciplined, and I hadn’t. I had changed very little and even more damaged than when I’d gone in. She had outgrown me, and I really didn’t care. She had affairs. I left. I still didn’t know what love was.

Thirty and fresh off parole, I went back to Bakersfield, and within two weeks robbed another bank. Got $5,500 out of that one and spent the money on women, drugs, alcohol, and hotel rooms until I found a woman I could move in with. It was back-to-back sex and lies: I’d say “I love you,” she’d say it back, and we’d both know it wasn’t real. But we didn’t care. Eventually I would rob another bank, rent more rooms, and party until I found another woman. It seemed like I’d been repeating this cycle forever, finding other lost souls and giving each other comfort until it wasn’t comfortable anymore.

I traded my motorcycle for a Volkswagen Baja Bug, which I took down to a used car lot as a down payment on a pickup. I did some work for a temp agency, bought some tool bags, and drove around Bakersfield stealing sprinkler heads from big business complexes. With a PVC cutter, channel locks, and a few parts, I then drove around the country club estates, hunting down properties with obvious sprinkler problems. I would knock on the door and tell them I could remedy their problems for $37.50 plus parts. Many agreed, and I’d walk away with $55. I bought more tools, stole more sprinkler heads, and made more money until I was picking up $200 a day.

After I injured my hand in a bar fight, I met a beautiful woman named Tammy at the doctor’s office. I had a cast on my left arm and she had a cast on her right foot. We moved in together. Our relationship never went beyond sex where I was concerned; I knew no other way. She said I just fucked her, that I never made love to her. I just crinkled my brows and asked what the difference was. She started having an affair.

Meanwhile, I kept building my sprinkler business. I posted an ad in the yellow pages: Aquamann Sprinkler Company. (I figured the extra n would keep the real Aquaman from getting me.) I made flyers and business cards and knocked on doors in the wealthy neighborhoods. I rented uniforms with my name patched on the chest. I was an excellent marketer of myself, and the quality of my work brought me lots of business. I met a very wealthy eighty-year-old widow who found me irresistible. She had so many things for me to do that I started working at her estate exclusively, abandoning all other calls. She had a big house and only lived in half of it. Guess what happened? Yep, I moved in with her, occupying the other half. Had sex with her twice. Then she died.

I hooked up with a childhood girlfriend, Robin, who had become a meth addict. The sex was phenomenal. I moved in with her and then we moved into my parents’ rental. Between the meth, the alcohol, and not building my business, I robbed another bank. I was arrested on October 24, 2000; in November I was given a three-strikes sentence of thirty-five years to life. I was forty years old and still didn’t have a clue what love was. I certainly didn’t find any in prison.

What passes for love among prisoners is the same love you might feel for a close friend. A sense of trust and loyalty with room for forgiveness and an element of exclusivity. I would forgive my friend for lying or stealing or having sex with my girl, but not a stranger. I can go to my friend’s cell and sit on a bucket and discuss this, figure that out. For instance, if I really want to put hands on someone I might consult my friend in private, to find out how he sees it, and not care what anyone else has to say.

I had no financial support at Lancaster State Prison, so I learned to make hooch, pruno, wine, whatever you want to call it. I got good at it and was making $20 every Sunday, making two gallons and selling one, then sharing the other with the “Wood Pile,” the other white inmates. I wasn’t concerned about getting caught—hell, I had thirty-five years to do and I was forty years old. Besides, I needed the things wine was getting me: food, weed, heroin. I was “in the mix” by choice; I would’ve been anyway, whether I liked it or not.

One day in 2004, I was in the dayroom with my hands cuffed behind my back, while two other guards searched my cell. After a few minutes they both came out empty-handed. I smiled. Then one walked back into the cell and just stood there. I wasn’t smiling now. He put his hand up, palm out, and put his index finger to his lips: sh-sh-sh. I knew what he was going to hear.

He looked straight at me with a smile, then got down on his knees and reached into the darkest corner under my rack and found a rolled-up army blanket. In the center were two gallons of hooch, just bubbling away. (I had a filtering system that masked the smell of fermenting fruit but bubbled continuously. At night my cellie and I could hear it cooking away; we’d say it was the sound of money being made.)

Now, as everyone looked out of their cell windows, I was cuffed with this guard gripping my upper arm as though I was going to take flight from a maximum-security prison. Watching him hold the army blanket like a trophy, I couldn’t help but smile again. “You’re really clever,” he told me. I thought, “The only way you could think I’m clever is if you’re really stupid.” The other guard squeezed tighter and shook me. I had said it out loud. What I didn’t say out loud was that I knew it was the guard who was clever: he wanted me to keep doing what I was doing so he could keep busting me. So that day I changed the game. I stopped making hooch and stopped drinking it too, and I would stand up to anyone who didn’t like it. I decided I needed an education. I needed mentors and friends who weren’t criminals, so that I could be more than a criminal myself.

In prison, the powerful groups make money for their organizations on the street. Drugs, gambling, extortion, alcohol, whatever sells. Prison is structured for that purpose and violence is the enforcer. But when a man decides that he wants to do right, to better himself through religion or education, he can walk his own line. He still has to “ride” if a riot breaks out or to back a homeboy’s play, but he doesn’t have to engage in criminal activity any longer. But he has to be genuine or he’ll get smashed on. Criminals pretend to have honor, respect, and loyalty. I say “pretend” because when you cross a criminal all of those virtues dissipate right in front of your eyes, replaced in an instant by hate. If I loved women for sex, I loved criminals for safety. But neither is truly love.

That day, standing there with my wrists cuffed behind my back and feeling the guard’s fingers squeezed around my arm, I decided I was going to go for it. I had a niece named Lacey who thought I was really something, but here I was doing nothing. Even if I had trouble with the people here, I would have her. I wouldn’t be alone. I decided to treat myself like I would treat someone I loved. I even said it in my head: I love myself! I can be a good man or I can end up living in a cell 24/7 in boxers and shower shoes. I chose to be a good man.

I chose to get an education so I could find out what a good man is.

When I was placed back in my cell, I was already a different man from the one who had stepped out an hour earlier. For the first time in my life, I felt worthy of bettering myself. I had found a little love, and it was for myself. I didn’t care much for the adults in my family, but I spent time with the children when I could, teaching them that they could make their own decisions and that everyone should respect them.

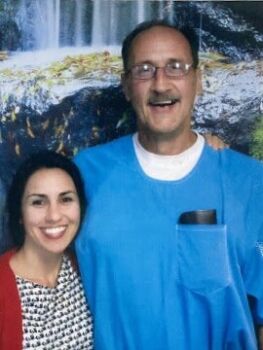

On one family visit to Pismo Beach, I walked hand in hand with a tiny little girl named Lacey, my older sister’s youngest child. As we walked on the pier, she saw fishermen ripping hooks from the mouths of the fish they had caught, and she asked me whether the fish could feel it. I told her I knew fish could feel the temperature of the water, but I didn’t know if they felt the hooks or not. Lacey later told me that having this discussion made her feel grown up. After I went to prison in 2000, she began writing to me. She was in her twenties at the time, and she’s been writing and visiting me ever since. Her kids, Olivia and Kael, love me and write to me too.

In general, love is not talked about in prison. But we do take great pride in being loved. I like saying that my niece loves the shit out of me. It makes me feel good, not so alone. It also signals to whoever hears me say it that I have some value and good characteristics. I’m in prison, but I’m not a total loser. Lacey has loved me long enough for me to finally come to terms with my childhood traumas, and to turn the love I feel for others inward. I recognize familial love without reservation as a great force of salvation. Putting aside criminal thinking and feelings of entitlement has allowed me to see the humanity around me; going to college has forced me to ask for help, and to specifically identify the challenges I was facing. From that help came a genuine interest in my own good. Where I once superimposed the face of a deceiver onto every stranger I saw, I eventually learned to recognize the help for what it is: love.

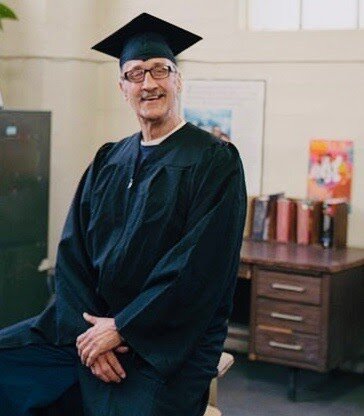

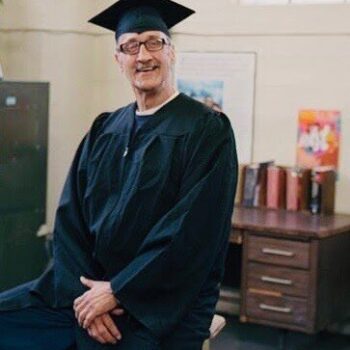

It took me nine years to get to the only prison that still had a college program: San Quentin State Prison. It was the first long-term plan I ever undertook. And it was within the Prison University Project, and thanks to Lacey, the one member of my family who never lost touch with me, that I discovered love on levels I had no clue even existed. (And guess what? No sex! Imagine that.) I started paying attention to what others were saying, spending time showing them I wanted them. I stopped getting in trouble. I talked to an educational guidance counselor, and we made a plan for me to work toward an AA degree. I still have the paper on which we laid out that road map toward college. When I began my first for-credit class in 2014, I had only an eighth-grade education, completed in 1973. Of the forty-one years in between, I had spent almost thirty in prison.

By 2017, the classes had become my world. I had never felt like part of a community, so I developed an apathetic view of people as a whole: I believed they wouldn’t like me because I was different, which made it easy to steal and rob from them. But as I became better educated, I began to identify with those people and recognize my wrongdoing. Realizing the suffering I had caused, the brutality and traumatizing effects of robbery, brought me to tears.

In retrospect, my tears of remorse were a sign that I had learned to exercise my apathy and internalize empathy.

With the critical thinking skills I was learning, I was able to go back in time and see things more clearly. I said there was no love in my house growing up, but looking back I see that there was. My mom was a victim too. She just didn’t know what to do with six kids and an alcoholic as her provider. And I saw that money was never the driving force for my crimes—I just blew it as soon as I got it.

Robbery, I discovered, is no more about money than rape is about sex. It’s about feeling powerful and in control. I realized that the abuse I experienced as a child and the helplessness I felt growing up were silenced by the power I felt when I was robbing a bank. All the criminal activity I participated in was either to feel in control or, in the case of drugs and alcohol, to not feel at all.

I can’t do anything to change my childhood, but I can change my life’s trajectory by learning how to manage my emotions and behaviors. Now, only two classes away from a college degree, I’m thriving socially and don’t feel powerless at all. If I start to, I understand and adjust. Problem-solving strategies give me the sense of control I’ve been searching for. Education may not be magical, but it has transformed me from a dangerous, callous, selfish, confused loner into an intelligent, mindful, conscientious, repentant member of my community. It plugged me in and connected me to an amazing world of amazing people.

When I finally looked inward with acceptance, forgiveness, and self-love, everyone around me became more human. I could see their ages and intentions. All of a sudden, as I said before, I wasn’t seeing threats, but opportunities.

I looked back and realized how many people had tried to help me in a loving way. I regretted my apathy and my heart ached at the rejection I must have made so many feel. I am so sorry to so many for not recognizing that they cared about me.

Every single person I have met associated with the Prison University Project helped me become the better human being I wanted to be, for no other reason than that it was what I wanted. And it’s because I’ve shared my burdens, and been open to helping others bear theirs, that I’ve been able to connect to the world around me. There have been times when a tutor was helping me that my eyes began to water:

I have made it. I have become a better human.

Letter to a friend

It’s been a while since I’ve written, I know. I’m taking a break from a writing assignment for a college class I’m taking. Today, feeling a bit melancholy, I took a walk down to the lower yard. As soon as I walked out of the cell block, the whole world changed. Leaving behind the noises and smells of a huge dank warehouse filled with eight hundred men is like walking out of a cave into the clear light of day.

Ensconced in my thoughts and alive in my senses, I merge into pedestrian traffic. I’m certain that people walk like they drive. I position myself safely behind the person in front of me, careful not to walk on his heels, hoping no one runs into mine from behind.

My walk is concrete, steel, prisoners, and guards until I reach the top of a staircase down to the lower yard. I pause at the viewpoint. Over the thirty-foot walls I can see for miles instead of yards. People in their cars and trucks, zipping left and right on the expressway. Freedom? I sometimes wonder if someone on the road has pulled over and is looking over here…

Seeing so far gives rise to a yearning that I have to dampen by continuing down the stairs. Forty-six steps. The lower I go, the higher the white walls rise. They reflect the sun’s rays and the hills are green and still. I see no more movement out there: the walls are too high now. I hear the echo of a handball game, shouts from the basketball court, the ring of steel horseshoes striking the steel pin. The comfort and safety and familiarity of a prison yard always surprise me a little. The melancholy is gone.

Do you take walks to change the way you feel? If so, write and let me walk with you.

Yours truly, Mike