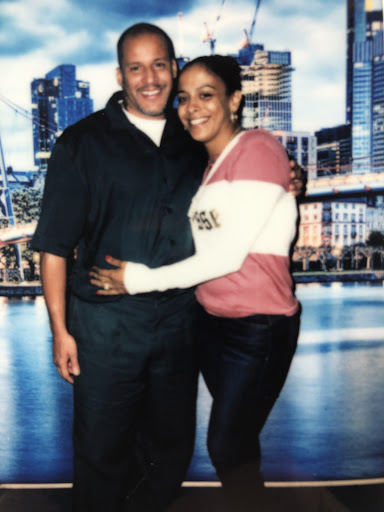

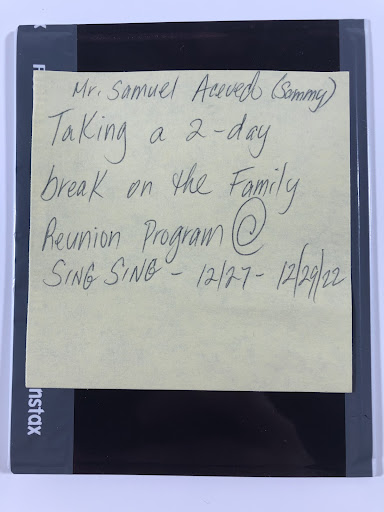

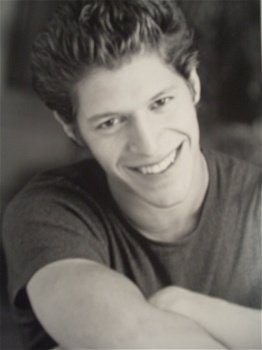

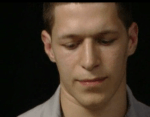

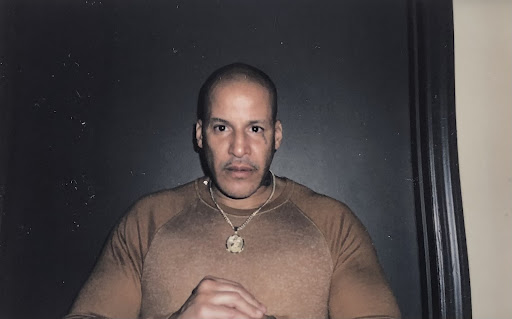

Sammy, 54

Meet Sammy…

I received a letter from my 19 year old daughter, Jazzy, asking me the most insightful question a father would ever have to answer, “Who are You?” And for the life of me, I could not write her a response.

Sammy, 54

Incarcerated: 22 yrs

Housed: Sing Sing Correctional Facility, Ossining, New York

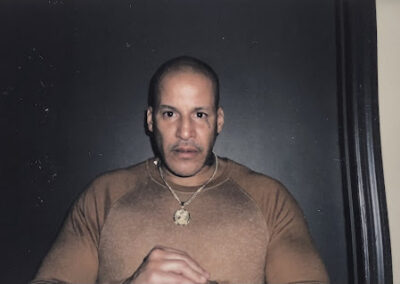

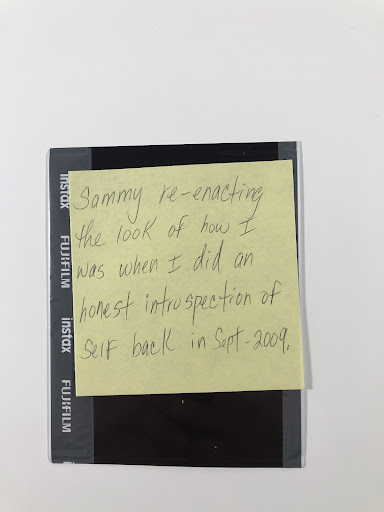

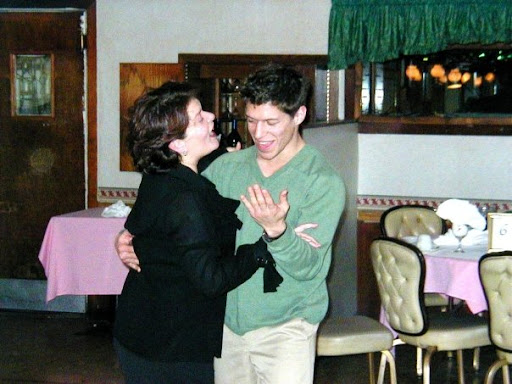

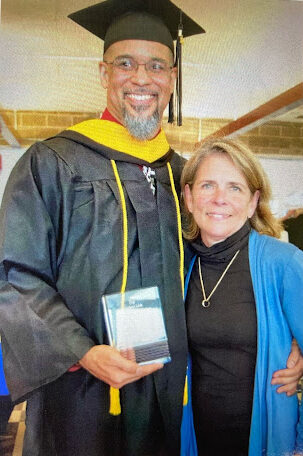

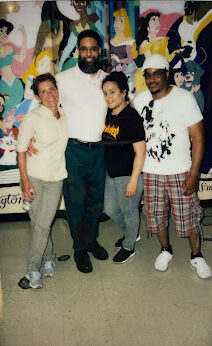

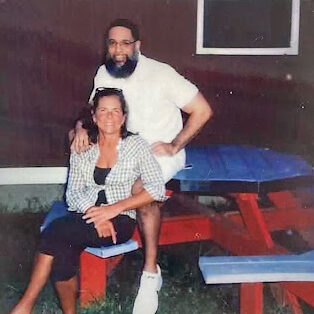

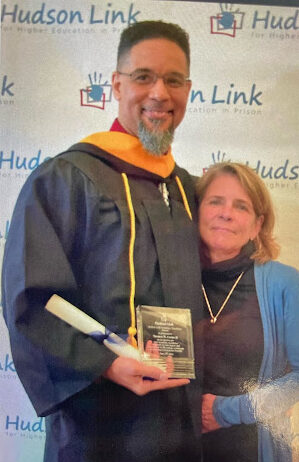

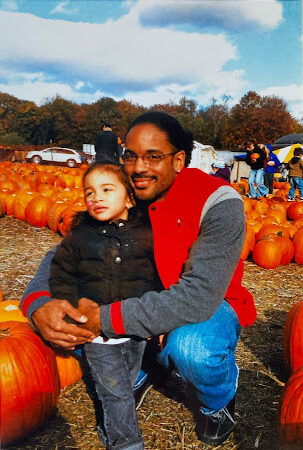

As a byproduct of the foster care system, I know what it is like to be frightened, saddened, and unbeknownst of what is to come. I know about the exhilarating feeling of being adopted and properly raised by a devout and loving Christian family. Unfortunately, since 18, I have been a career criminal gripped and enslaved to the disease of heroin addiction. And as a result, I mentally and physically wounded too many good-hearted people, especially those I made out to be victims when I needlessly took the life of another human being. I am currently serving 25-years-to-life. Even after that horrific and needless part of my past, I still continued with drugs and criminal thinking. In 2009, I received a letter from my 19 year old daughter, Jazzy, asking me the most insightful question a father would ever have to answer, ‘Who are You?’ And for the life of me, I could not write her a response. Instead, I was miraculously drawn, in tractor-beam force, to look in the mirror in my 8’x8’ cell. As I took an honest look – the image that gawked back, was just a shell of me. I then began to walk the journey of honest self-introspection, which allowed me to stop blaming others for my negative thoughts and behaviors. Instead, I took responsibility for the harm I caused by first abstaining from drugs. Since, I have become a facilitator for the Alcohol Substance Abuse Program, obtained college degrees and am working on my master’s. Do those accomplishments make up for all the harm I caused others – of course not. It is the only concrete way in which I can add substance to the words ‘I’m Sorry’ to all I have harmed. Today, the answer to my daughter’s profound question: I am an individual who is not defined by my bad decisions, yet my past experiences have molded me into a proud, loving, and remorseful Latino father of six wonderful kids and five amazing grandkids. I am also intelligent enough to know what my limitations are – and that recovery from the disease of drug addiction cannot be done alone. God has gifted me with the humane blessing of using my past to help others better themselves.

————-

Sammy, 54

Incarcerated: 22 yrs

Housed: Sing Sing Correctional Facility, Ossining, New York

Who am I?

I wasn’t born to be a heroin junkie, career criminal, or a murderer, yet the consequences of my deviant thought process and bad decision making allowed for my loved ones and society members to appropriately label me as such. The question that needs to be answered: Who Am I? Why would a young innocent child labeled as a “Mama’s boy, jokester, and decent kid,” turn out to cause so much harm to civilized members of society, his loved ones, and to himself?

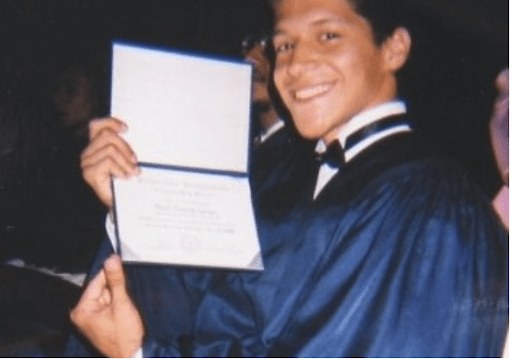

At the age of four I was displaced from the care of my mother by the Bureau of Child Welfare, after it was revealed that my single mother was endangering the lives of her sons by physically and sexually abusing them. The blemish of that part of my story is that I had become a product of New York City’s foster care system. The unforeseen benefit to that sadden event was that I was chosen to be fostered by a loving, supporting, and devout christian family. I had adjusted well to being raised by a Roman Catholic family of six (foster mother/father, and two older foster sisters and brothers); in fact, life for me was going extraordinarily well. I was nurtured, my immediate needs were met, my academic studies in elementary catholic school was good, and I was as happy as a kid of my age should have been. Unfortunately, that positive lifestyle drastically changed when a family court judge made the notice. I had developed the tendency of not voicing myself when addressed by my family, teachers, community members, and psychological medical staff whenever I committed a wrongful act. Soon thereafter, said caregivers had started to witness the beginning stages of my juvenile delinquency. For example, stealing snacks from the local neighborhood bodega, money from family members, and more frustratingly to them, I had developed the harmful tendencies of emulating the criminal behaviors that were associated with the hoodlums in my East Harlem housing projects. As a result of my poor school grades in elementary school, my parents had to enroll me in a public high school. They got me into the best one that had an R.O.T.C. program; and the plan was for me to go straight into the military after obtaining my high school diploma. Remarkably, that plan went extremely well throughout my freshman year. I had excelled in my academic studies, and I was enthralled with the dynamics associated with the R.O.T.C. program. That was until in my sophomore year when I had impulsively given into those negative childhood tendencies of emulating those neighborhood law breakers that my parents did their best to shield me from.

Consequently, upon getting a pass to go to the bathroom from class one afternoon, I had walked right into those same types of individuals my parents had warned me to stay away from. What was more troubling, they offered me to smoke marijuana with their crew, and my immediate response was, “Yeah!” Having never actually smoked weed before, as soon as I lit that joint and inhaled it too hard, everyone in attendance knew because it looked like I was trying to cough up a lung. And rather than run out that bathroom red-faced with embarrassment, I instead laughed right along with them. Instead of feeling like a loser from them ridiculing me, I ridiculed them back, and in that moment, I had finally lived out my mental fantasy of being accepted by a group of respected and feared bad-asses from my neighborhood. That same warped process of mine had led me to drop out of high school on the second day of my senior year; it had also been the beginning stages of the many negative thoughts and bad decisions of my youth, and ultimately my adulthood.

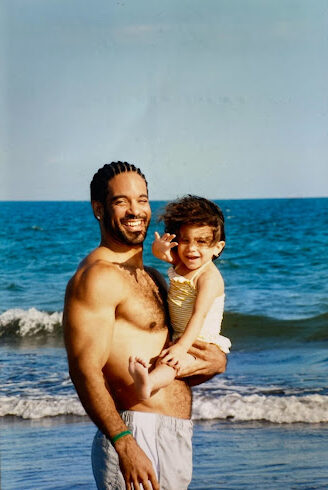

On my 18th birthday I tossed my clothing out of my parents’ 14th floor apartment so that I could run amok in the streets of East Harlem. And as a result, I caused my mother to painfully cry in a way that still haunts me to this present day. I had also defied the words of my father, when my mother had been pleading with him not to let me go, as he said “Let him go, he won’t last a day in those streets.” I had proven him incorrect, but it came with the cost of me causing too much hardships and harm to my family, friends, community and society members, and me. One of the proud moments from those years was the birth of my children, but they too ultimately were subjected to needles, heartaches and let downs from their dad. Aside from that, there were many times where I attempted to live according to the 9-to-5 working class norms, but it was short-lived, regardless of how good the job or life was. I had consciously decided to commit myself to a life of criminality. I became chemically dependent on the nasal usage of heroin. I got arrested for possession of narcotics, with an intent to sell. I pleaded out and received five years probation. Again, I was arrested for the same charges two days before my youngest son’s 1st birthday – I pleaded out and was sentenced to serve two to five years in the state prison. I completed the Shock program and was back in the streets doing the same thing with the same people, places, and things, ten months later. While on parole, I was once again convicted of the same charges and sentenced again to state prison, in which I served two years with the same outcome. While on parole, my chemical dependency went to the extremes. I had a $100 a day heroin habit and nothing else mattered in my life except finding a way and means to support said habit. In fear of violating the terms of my parole, I successfully completed a detox program and went directly into a residential drug treatment program. Unfortunately, that program was located a block away from the same neighborhood where I harmed too many people. And as a result, I was confronted by a drug dealer that I had once robbed and it ended in a violent altercation that was not favorable to the aggressor who tried to attack me. Fearing the worst, I left the program because I did not want any of the residents getting hurt in case he came back to retaliate while I was in the program. Against the advice of the staff members, I went back to living in that neighborhood and I dealt with the matter at large. Consequently, I relapsed with my heroin addiction in the worst way possible.

On April 1st 2001, I was out scheming for a way to get my first heroin fix of the day and I got involved in a situation where I needlessly killed a person who was once a friend of mine. The end result was as follows:

- On April 11th 2001, I was violated by my parole officer, then picked up by the 32nd precinct homicide division and interrogated for over 17 hours.

- On April 12th 2001, I was arrested for murder in the second degree.

- On April 3rd 2003, after a jury trial, I was convicted of that crime.

- In May of 2003, I was sentenced to serve 25 years -to-life in state prison.

Throughout the two years I ran rampant in Rikers Island, and the first six years running wildly in several state penitentiaries, I always found a way and means to continue with my chemical dependency with heroin, even though it came at the expense of risking the freedom and livelihood of others. After being found guilty for my fourth positive urinalysis offense, I was once again sent to solitary confinement to serve a 60-day sentence. At mail time in my cell one afternoon, I was delivered a note from my 19 year old daughter Jasmine. In that letter she challenged me to answer for myself the most profound question a father should ever be asked by his daughter – “Who Am I?” And for the life of me, I could not write her back an honest response. Jazzy challenged me with that profound question. It stunned me in such a way that I instinctively walked up to the mirror in my cell so as to take an honest look at myself. And because of me not accepting the image that gawked back at me, right then and there, I vowed to do an honest introspection of self, so as to get the answer.

Upon release from Rikers solitary confinement, I was transferred to Clinton Correctional facility where I began a self-introspection journey for Narcotics Anonymous. One year later I was transferred to Sing Sing Correctional Facility where I utilized the rehabilitative self-help programs that solidified my efforts towards understanding who I am. In fact, the central part of my cognitive therapy treatment came from the Alcohol Substance Abuse Treatment (ASAT) counselors in Sing Sing, and practicing the nine competencies of drug treatment. I came to the revelation that my flawed thought process and bad decision making need not define me but instead prove who I am today. Therefore, I formulated a plan of action that could transform those negative experiences of my past and transform them into a positive educational learning experience. I adopted the habit to always ask myself, “What can I do next towards the goal for positive growth and development?” This has led me down a productive path to a Master Degree in Professional Studies.

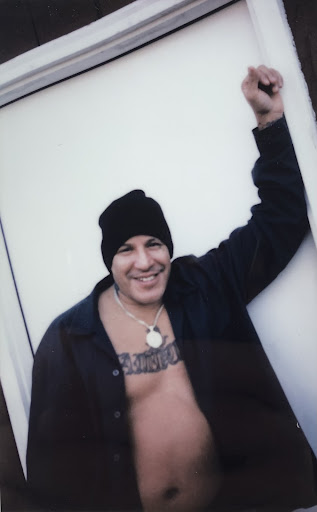

On completion of documenting my journey towards an honest introspection of self, I can now answer with confidence and certainty that profound question that my then 19-years old daughter Jazzy had once challenged me to answer for myself, “Who Am I?” To begin with, I must accept the fact of who I am not. Today I am not a heroin junkie, I am not a career criminal, and most of all, I am a man who has learned to understand there will never be any justification for why and how I needlessly took the life of another human being, regardless of traumas that were associated with my past. The trials and tribulations of my life experiences have molded me to become a remorseful, loving, moralistic, and fun-loving person. I am also a goal-oriented individual who strives for personal success, while supporting the journey of others who are striving to better their lives. Moreover, today I understand that the words “I’m Sorry” have no sentimental value unless there is some concrete evidence to support such remorseful language; evidence such as converting the negative labels of my past and transforming them into credentials for my future endeavors. Credentials that can open the doors of opportunity for me to work with those that are presently fighting against risk factors that prevent them become better people in society. I know that I have what it takes to be a father to my children, a laudable son and family member, and a potential credible messenger who will always do my best to not repeat the bad decisions of my past, but use them as a harm-reduction educational experience for others.