My incarceration has been a very long road, sometimes easy and often uncertain, but one thing it hasn’t been is a waste of time. At the beginning, as a screwed-up teenager, I looked at prison and the thirty flat years before I saw parole as a great behemoth that would surely crush me. Now I can’t imagine what I would have become without it.

Born and raised in Houston by loving grandparents, I fell into depression and drugs as a teen. With no genuine friendships or romantic relationships, I was a wayward, thwarted youth—my own worst enemy. My downward spiral resulted in a murder when I was nineteen. I received a ninety-nine-year sentence, of which I have now served twenty-four years now. I’m forty-three.

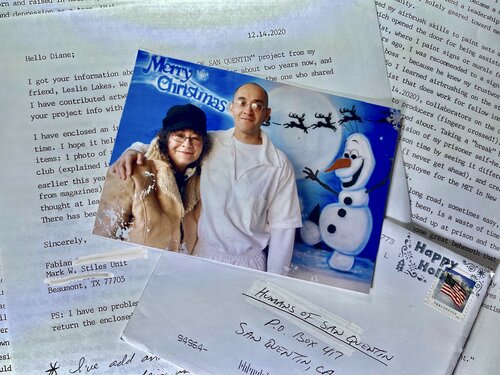

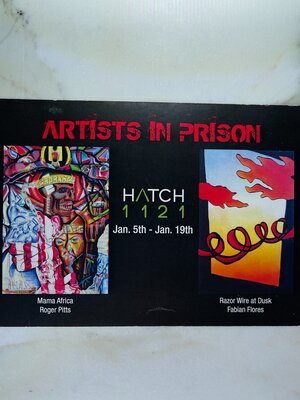

With the undying love and support of family and friends during the early years of my incarceration, I managed to overcome many dark, burdensome years of guilt, shame, and self-hatred. For a long time I couldn’t imagine the light at the end of the tunnel, but gradually I rekindled my love of art, which helped me gain control of at least a minor part of my life. In turn, I recreated myself from the inside out. In the mid-aughts, I exhibited drawings, collages, and watercolors at countless grassroots venues and prisoner-support events around the country.

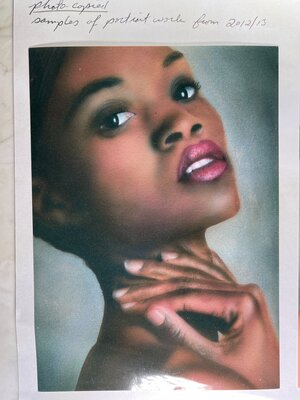

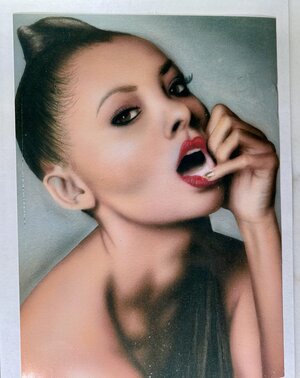

Emboldened by a greater sense of self and purpose, I began volunteering in the chaplaincy department to run sound for religious services, family day events, and GED and college graduation ceremonies. More recently, I have used my airbrush skills to paint sets and costumes for the unit’s drama club, which opened the door to the position of assistant director. I paint signs or murals for the wardens and other staff. Along the way I discovered a new passion as well: scriptwriting, with the future goal of directing. I’ve nurtured this dream for about fifteen years now, writing countless crappy scripts, studying movies on dayroom TVs, reading every film-related book in the unit library, and asking my family for subscriptions to movie/filmmaking magazines (they spend more on this than they do for commissary, which irks them).

All of these learning experiences have led to new opportunities. By running sound for events through the chaplaincy, not only did I learn sound fundamentals that would help me in my own films, but I also became a member of the prison leadership community, which earned me an invitation to a mentorship conference sponsored and hosted by outside groups. A former boss recommended me to a sign shop on the strength of my trustworthiness, work ethic, and passion for art—so I learned airbrushing on the state’s dime, and now I’m a proficient portrait artist who does work for fellow inmates and staff alike. And in 2009, I entered my first script excerpt to the PEN American Center’s annual prison writing contest, and was enlisted in their mentorship program.

As I write this, collaborators on the outside are shopping some of my scripts around to producers—fingers crossed. I’ve just finished a new script that I’m super hyped about; on my “break” before I begin the next one, I’m on the second revision of a self-help book that shows prisoners how to live their prison time better by seeing it differently, as well as catching up on portraits for guys in here (I never get ahead) and creating art for a friend and collaborator (and former employee of the Met in New York) who has exhibited and sold my work since 2004.

Social awkwardness was always my handicap: I was a naturally introverted kid, and it only worsened in prison as I tried my hardest to stay away from gangs and negativity. But I was determined to be a film director someday, so I joined Toastmasters to learn public speaking. I was scared as hell, but I did it anyway. I struggled and sweated for a year and a half until I received my Competent Communicator certificate—and two years after enrolling, I was voted club president. In addition to becoming an effective public speaker—something that has since helped me in meetings with producers, investors, and actors—I also became something I never thought possible: an effective mentor. An effective human being. Naturally, a new passion sprouted: motivational speaking.

In dramatic writing, you’re taught that the protagonist blindly struggles toward something they think they want, but by the story’s end their eyes are opened and they discover what they had truly needed from the start. Sometimes life can be a gift like that.

As the great director Stanley Kubrick said: “However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.”