Thousands of incarcerated sons and daughters sit helpless, unable to be there as their parents’ voices grow weaker with every passing day.

Daddy

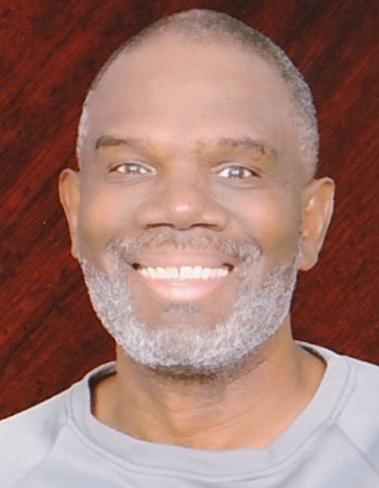

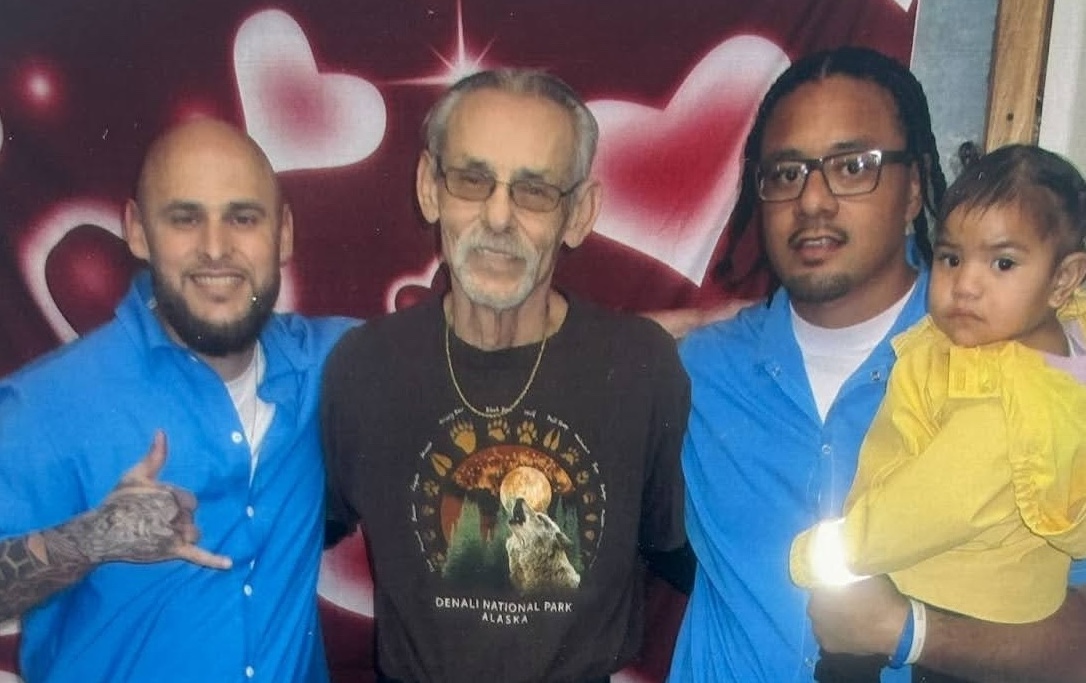

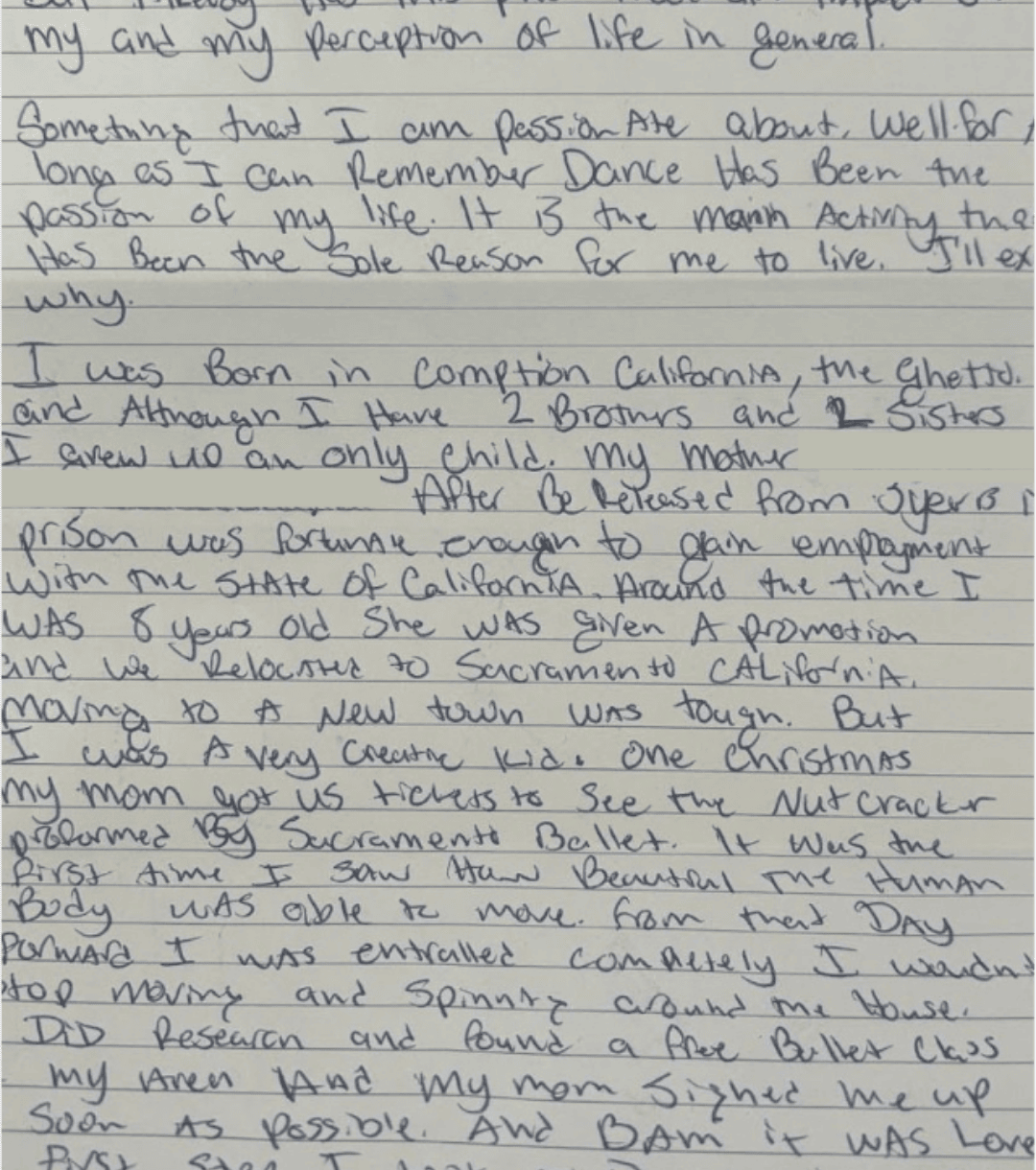

“Hi Daddy,” I say, trying to hide the sadness in my voice. “How are you, number one son?” he replies, his tone still cheerful at receiving my daily calls. But I can hear it, the change in his voice, a slow fading of life. My 82-year-old father is dying of stage-four prostate cancer. It’s spread to his bones, and all that medical science can offer him now is a dignified death. He’s in home hospice, with a nurse administering morphine because his esophagus is too weak to swallow pills. My dad was never a big man—5’7” 165 lbs. Now, as he withers from the cancer, pain, and loss of appetite, he weighs barely 100 lbs. My faith tradition teaches that death is a part of life, especially for children of parents my dad’s age. It’s a difficult experience, one some can handle better than others. But what makes my experience more painful is the distance. I’m incarcerated nearly 3,000 miles away from my dad’s home in south Daytona Beach, Florida. I won’t be able to visit him. I can’t hold his hand or attend his funeral. All I can do is sit on the other end of the phone line and hear his life slowly fade with each call. This pain is not unique to me. Thousands of incarcerated sons and daughters sit helpless, unable to be there as their parents’ voices grow weaker with every passing day. Many of us are serving life sentences, losing siblings, extended family, friends, one by one, to death. With each loss, we become more isolated, more alone. Perhaps some of you reading this have experienced similar loss. If so, please know that I empathize with you. My hope is that by sharing my story, you realize that, even though we are incarcerated, we love, we hurt, and we feel pain. We experience loss because, above all, we are human too.