Watch the video of Diane’s interview with Mark:

Watch Video:

Video Transcript

Diane: So thank you, Mark, for sitting down and being interviewed by us today. We’re excited to have you and especially appreciative of you trusting us so long ago. I know you wrote to us a long time ago when we were just starting, so I appreciate your trust. Thanks so much for being here today. I can’t wait to hear your story.

Mark: Yes, thank you. I really appreciate it. I’m very honored. I got to San Quentin back in December 2012, and I paroled from there in June 2020.

Diane: How did you feel when you first found out that you were going to be released?

Mark: I was beyond words. I couldn’t believe it. I had been dreaming about it for all those decades I was incarcerated, and I never thought the day would come. At the same time, I believed it would happen, so I had mixed emotions. It’s something that I, along with so many other lifers, dreamed about for so many years—wondering if we would ever make it out alive. When it happened, it was so surreal. I was at a loss for words. I didn’t know how to describe it because it seemed so unattainable. It happened during COVID, so the timing was incredible. I was just so grateful to be out.

Diane: So that was what year?

Mark: June 2020.

Diane: So it’s been a hot second since you’ve been out?

Mark: Yeah, it sure has.

Diane: How did that transition go immediately after you were released?

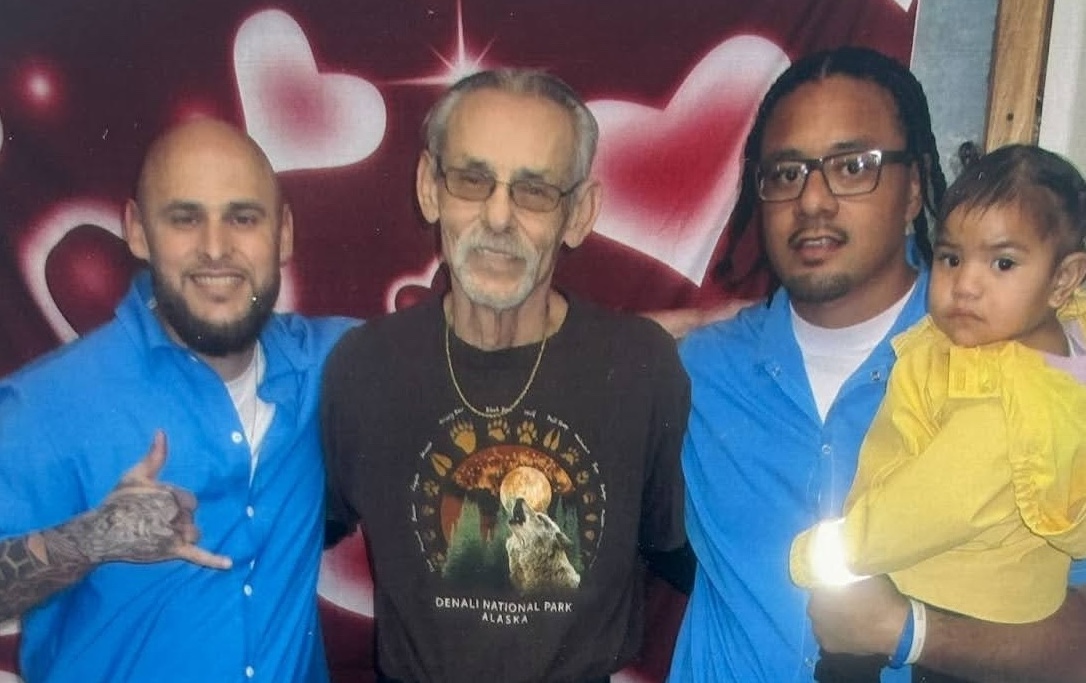

Mark: My mom came and picked me up. My dad was down here in Southern California, so my mom actually drove all the way up to San Quentin from Long Beach. It was just so awesome to see her at the gate. I remember being in the van, which had one other guy in it that I knew from the San Quentin baseball team. He and I were both being released at the same time, and he was also a fellow three-striker. I remember getting out and trying to think of what gate it was, but my mom was waiting right there. I could tell how nervous and excited she was at the same time, and I had butterflies in my stomach. I jumped out of the van with my box of property, and my mom ran up to me. It was powerful; I hadn’t seen my family in a long time, and being able to hug my mom after all those years was really something. We ended up going to a burger joint not too far from the prison. I could actually see either the south block or west block from a distance. Sitting there eating that burger, drinking soda, and enjoying all that delicious food for the first time in so many years, with my mom—it was something I’ll never forget.

Diane: So where did you parole to?

Mark: I ended up paroling back home to Long Beach. But before I could do that, I had to go to a transitional house I had picked, which was required by the parole board. You have to find at least two places to transition to for six months. There were 15 guys in that house. It was really nice, and I met a lot of great guys there in the same position I was.

Diane: Did you get along with them all?

Mark: Yeah, for the most part, we all got along pretty well. I ended up meeting a guy named Terry, who did about the same amount of time as I did.

Diane: You were lucky to get out before COVID really hit inside because that was an absolute disaster.

Mark: Yeah, oh my goodness, I heard what happened in San Quentin. I couldn’t believe how many people got sick and how many inmates died. I heard about all the death row inmates passing away, and so much of the population got sick too. I felt so grateful to God. I felt terrible for everyone in there, but I was so relieved to have made it out, especially being in such close quarters.

Diane: They were like in their cells for 18 months. So here you are in your transitional house. Were you in that first one for six months?

Mark: Toward the end of the program, I couldn’t remember the exact reason, but they ended up splitting us all up, which was sad. I was at work at the time, maybe a couple of weeks into it, and then one day, one of the sponsors, who was also a formerly incarcerated inmate, called me and said, “Hey, Mark, you need to return to the house immediately.” I panicked, thinking, what’s going on? Why would they be in such a hurry to get me back? I was paranoid because I had just gotten out, and I didn’t remember doing anything wrong. I begged him to tell me what was happening. He said, “Well, they’re closing the program down; it’s losing its funding.” They ended up shipping us out that very day. I got sent to Compton, just a couple of miles from the house. At first, I thought, oh my God, I’m going to Compton, but it worked out well. The person running that program was great. She was very nice, and I met another group of pretty cool guys.

Diane: So what happens next? You’ve got a job, you’re working, you’re riding your bike, you’ve seen your parents.

Mark: I ended up losing that job because I had to transfer to Compton. That was quite a distance away, so I had to let the job go. I came back home in December 2020 and finished my transition time. The six months were up, so here I am at home, on parole, and not working just yet. I finally found a job—I’ve had a few temp jobs since I’ve been out, trying to keep myself busy and help my parents. Unfortunately, I had a setback in 2023; I ended up getting arrested again after all that time. Oh, that was devastating. It was January 2023. That had a more significant impact on my life than my previous arrest, even though that resulted in a life sentence. Being older now, it really shook me to the core when the FBI showed up at my house.

Diane: Yeah.

Mark: That was scary. I felt terrible because after all the work I had done in prison, all the programs I attended, going to college—even though I didn’t earn a degree—I just wanted to see if I could achieve things I didn’t believe I could. So, all that came back to me when I got arrested again. It all hit me so quickly. What was I thinking?

Diane: How scary. Do you want to go into more detail about the arrest, or how you got there? I don’t want to push you on anything you’re not comfortable with.

Mark: Around 2021 or 2022, I had gone online. I had never seen the internet before, never had a cell phone, so all this was new to me. I was captivated by the technology. Somehow, I came across laser pointers, and I thought they were really cool. I found a company selling high-end lasers and ended up calling them to ask about it. I was in my backyard, exploring, shining it in the clouds, amazed by its power. I didn’t think I could do anything wrong.

Diane: And you were kind of like a kid at that point, right? Ordering stuff and trying to have fun after all those years.

Mark: Exactly! I couldn’t believe how far it could go. I thought, this is incredible! Then I started pointing it around the horizon. I was trying to be careful, but I ended up striking a police helicopter.

Diane: What are you talking about?

Mark: Yeah, I didn’t realize it was a police helicopter until later. There were two different incidents. I wasn’t trying to hurt anyone, and I’m not trying to deflect my responsibility, but I told the FBI when they came to arrest me that I wasn’t trying to hurt anyone—it was strictly out of curiosity. When the helicopter was flying a couple of miles away, I struck the back of it without realizing the laser could travel that far and cause a reaction.

It turned into a situation where I thought, oh my God, look what this thing can do! I caused the helicopter pilots to have to come back and search for my location, and my heart started beating really fast. I was scared but excited at the same time. I felt like a kid—immature and irresponsible. I wasn’t thinking about the consequences. I was putting those pilots in harm’s way. I didn’t realize my actions were dangerous. These guys were out there doing their jobs, and I felt terrible for betraying so many people. I’m grateful to be talking to you today, because if it weren’t for my parents and my family—being raised to be respectful to others—I would have lost that part of me.

After this arrest, it really woke me up. I was 46 years old then, and now I’m almost 49. I think about my future and the choices I make. I remember the groups I attended at San Quentin, and I should have internalized what I learned. I had a relapse prevention plan, but when I got out, I only looked at it a handful of times. I didn’t take my freedom seriously or stick to my values. I didn’t apply the lessons I learned from those groups like anger management and others. I even attended AA, even though I’ve never had an alcohol problem, just to be part of something. Then, when I got out, I didn’t practice what I had learned.

Diane: What is it that you would learn in those groups that you didn’t apply to your life?

Mark: I took the group seriously at the time because we were in a structured environment, and we were sharing intimate stories about our childhoods and past traumas with a lot of other men. Then, when I got out, I wasn’t practicing what I preached. I had promised myself that I would reach out for help, call someone, and hold myself accountable. I should have called my parole officer to say, “Hey, I’m having trouble.” But I was scared.

Once I had already bought the laser, I didn’t want to say anything. He later told me after I got arrested, “Mark, you could have just told me.” I replied that I was afraid to tell him anything. I was also scared to tell my family because I felt so ashamed of myself—at my age, buying something that, while essentially a toy, turned out to be a very dangerous one.

Diane: It’s great that you can see that now. That’s wonderful. Does this crime correlate with your first one?

Mark: In a way, it does; in a way, it doesn’t. The first crime was for arson, which involved a series of events. There were two counts I ended up getting charged with, and I later pled guilty, accepting responsibility for what I did. I was so bored with my life and hated the person I was at that time. I didn’t take life seriously—my freedom, my family, my community. There was so much I could have done out here. I had so many opportunities to volunteer and help others, but I didn’t take advantage of any of that. I’m glad I can share this today because I want people to know that when you have too much time on your hands, that’s usually when bad things happen.

Diane: I hate to hear you be so hard on yourself, though, because you have so much against you. You’ve got a felony on your record, which you have to account for whenever you’re looking for a job, and it’s so difficult. I’ve seen other guys compare themselves to people their age who never went to prison and look at what their lives have become. You probably also feel the expectations from your parents, as well as the expectations you have for yourself. Then, to reoffend like that, there’s so much pressure. I don’t want you to be so hard on yourself; it’s really tough to pick yourself up after being incarcerated. But I’d love to hear you take us back to the time when you were arrested. What exactly were you arrested for?

Mark: I heard a siren, and my heart sank. I knew right away it had to be for me. My whole body went numb, and my heart was in my throat. I realized I had made the biggest mistake of my life—my worst decision ever. I went through the back door into my bedroom while my mom was at the front door. I could hear her talking to someone but couldn’t tell who it was. I figured it had to be the police. I then heard them order my mom out the front door and tell her to put her hands up. I thought, “Oh my God, my mother hasn’t done anything wrong.” But that’s what they had to do. So my mom came out at gunpoint, and I immediately surrendered, coming out with my hands up. They told me to lift my shirt. They took my mom aside and had someone console her. There were at least a dozen police officers, and a helicopter was hovering overhead, shining a searchlight on our house.

Diane: Oh my God.

Mark: Yeah, it was really bad.

Diane: Was it nighttime?

Mark: Yes, it was at night. The searchlight was illuminating the entire area. There were at least four or five police vehicles out front, one parked in the yard. At least two officers had their guns drawn on me. I complied, lifted my shirt to show I wasn’t armed, and my heart was racing. They took me into custody and put me in a patrol vehicle across the street. A wave of emotions washed over me.

I prayed and told God how sorry I was for everything. The next thing I knew, the FBI showed up, and I thought, “Oh my God, I know I’m in trouble now.” An officer got me out of the back of the vehicle, took me to the garage by the side of the house, and removed my handcuffs. The two FBI agents introduced themselves, saying, “We’re the lead investigators in this. This is now an FBI matter.” I thought, “Oh my God, the FBI. They’re no joke.” They were professional and treated me with respect.

I accepted that this was my fault. They told me, “We’re here for the laser. The judge signed off on the search warrant; he wants the laser.” They didn’t want to tear apart my parents’ house, and I thought, “I have to do this for them and for myself.” So they ended up arresting me for discharging a laser at an aircraft—two counts. I went to jail, which is one of the worst jails in the United States: LA County Jail.

Diane: It was immediate? You didn’t have a trial, right?

Mark: Right. There was no trial because it was just for the parole violation. I ended up getting out about 11 days early because the county jail is so overcrowded. I was relieved to get away from that place. I want to back up a moment: when the FBI arrested me, my dad suggested that I call the FBI to tell them I got out because it would look good for me. He said, “You want to be honest and responsible.” Sure enough, my dad was right. When I got out early, the FBI came to see me at the county jail. They interviewed me to let me know, “We’re taking over. We’ll be arresting you when you’re released from this parole violation, and we’ll come pick you up.” I thought, “Oh man, I thought I was getting out.” As it turned out, I ended up getting out, and they didn’t come pick me up. Part of me thought maybe they didn’t know I got out early, assuming I was supposed to be released on April 1, 2023. I ended up getting out around March 20 or 21.

It was actually a good idea to inform them, because when I did, the agent who had arrested me couldn’t believe it. He said, “Oh my God. Hey, what’s going on, Mark?” I told him I had been released. He said, “Really? Wow. We had you down for April 1.” I explained that the county jail was overcrowded and they let me go early. I asked, “Should I turn myself in now?”

He said, “Because you’ve been honest and came forward, you can go home to your family.” He told me when to turn myself in and warned, “If you fail to do that, it won’t be good for you, Mark. Make sure you’re there.” Not only did I turn myself in, but I did so early. They came and picked me up at the North Long Beach police station, just a mile from my house. Again, they were very professional.

Diane: So what’s the next step then?

Mark: Basically, the FBI didn’t promise me anything. They just said, “You’re probably going to be able to get a bond.” I thought I would have to stay in a federal facility throughout the entire process, but they said, “Because you turned yourself in and cooperated by giving us the laser, and considering your parents are elderly, we’re going to be cool with you getting a bond.”

I was shocked because the judge didn’t want to let me out. She was adamant. It felt like a miracle because I had been praying and going to church, asking God to take over everything. They let me go but placed many conditions on me. After that, I ended up getting almost a year of house arrest, but I was allowed to work and go to church. Last year, I pled guilty, took responsibility, and now I’m just waiting to be sentenced. I had an interview with the probation department, and believe it or not, I was surprised to hear they’re only asking for a range of 27 to 33 months.

Diane: Is that in custody?

Mark: Yes, in custody, in federal prison, but I don’t know where I’m going or if I’m even going. I’m preparing myself for the worst-case scenario.

Diane: How are you feeling, given that you’re thinking about the worst-case scenario? How are you feeling about being in custody again?

Mark: It’s something I never thought I’d imagine putting myself in this situation again. Thoughts are running through my head: Where am I going? Is there going to be a lot of violence there? Which facility? How close will I be to home, or how far away? They could ship me all the way to New York or Florida. It’s horrible because my parents are 74 and 75 years old now, and this is really devastating.

Diane: Right, especially with the 23 years inside.

Mark: Yeah, it’s scary. The feds are a lot different than the state; there’s much more involved. I have an opportunity to present myself in front of this federal judge to show him a different side of me—the human side—realizing that I made a mistake and how I will handle things differently in the future when I get bored or lonely, which contributed to this behavior.

After getting out during COVID, I felt like I was in a bubble, watching life pass me by. I was cruising around on my bike, skateboard, or scooter, seeing everyone else having a great time. I felt like I was living vicariously through others, thinking, “Man, I wish that were me. That guy has a girlfriend; that guy has a wife and kids. I don’t have that.” I felt so lonely and isolated. I didn’t reach out to many of my friends—most had moved on or started families in other states. Two of my childhood friends died while I was in prison, so I never got to see them again. It was really tough.

So, all of this was swirling in my head, and when I bought that laser, it distracted me from my reality. It was a way to escape from not being responsible, not saving money, not saving up for a car, and not being independent by moving into my own place. I started to really hate myself after all those years in prison. I had plans and parole goals that I should have followed through on, and I felt like I let everyone down—my family, the system, and myself.

Reflecting on it all, I’ve learned a lot about the consequences of my actions. I envision, “If I do this, this is what will happen.” I’m also getting help; I’m seeing a therapist, which has been invaluable in understanding myself and why I think the way I do. I’ve even started medication, something I didn’t want to do initially because I thought I could handle it on my own. But in reality, I couldn’t. I need help and intervention to get back on the right track. One key lesson I’ve learned is that I always thought I could overcome my issues alone. But I’ve realized that’s not true. Swallowing my pride has been important.

Diane: That’s a crucial message. If you could share advice with others facing similar challenges, what would it be?

Mark: I would tell them not to be ashamed of reaching out for help. Put aside your pride and ego—those things can prevent us from doing the right thing and seeking help. That’s the first step.

Diane: If you could go back in time and give your younger self advice, what would you say?

Mark: I would say, “Mark, you’re on a path of self-destructive behavior, and you need to get it together. Start liking yourself and accepting who you are. Don’t be ashamed of yourself. Be yourself. You have to love yourself before you can truly love someone else.” I didn’t believe this before, but I see how true it is now. Loving myself will allow me to heal, and then I can do the same for someone else.

Diane: That sentiment comes up often in conversations with people who are currently incarcerated or have been previously. It’s profound, but truly looking at loving yourself involves confronting all the things you dislike about yourself, which isn’t easy.

Mark: It really isn’t.

Diane: I hope you’ve been able to apply what you learned in the programs while you were incarcerated.

Mark: Yes, absolutely.

Diane: What simple advice would you give to someone who feels lonely or isn’t feeling good about themselves? You mentioned your relapse plan, which you didn’t use, but what can help others avoid reoffending?

Mark: One simple piece of advice is to build a support system. Surround yourself with positive influences—people who genuinely care about you and your well-being. Engage in activities that give you purpose and fulfillment. Keep yourself busy and set achievable goals. It’s crucial to stay connected to community resources, whether through programs, therapy, or peer support. And most importantly, don’t hesitate to ask for help when you need it. Taking that step can be life-changing.

Yeah, I would really like to tell them that they’re not alone in this. If you feel like you’re in a tough situation, you’re really not alone. If you start having thoughts of reoffending or committing a crime, that’s the moment when intervention needs to happen. Talk to a family member, talk to a friend—reach out. That’s what the accountability list is for. I had a huge accountability list that I didn’t use.

For anyone out there who’s going through this, thinking about committing a crime, or having negative thoughts about themselves or their environment, the very first thing is to admit that they have a problem. They need to call someone right away, even if it’s their probation or parole officer; they’re there to help. As scary as it sounds, you might think, “Oh my God, if I tell them this, they’re going to violate me or send me to jail.” Back in the day, they would have just violated you. Oh yeah, you’re going back. We’re testing you; if we find out you’re dirty, you’re gone. But now they give chances; they’re trying to help. Incarceration should be the last resort.

Diane: Yeah. I love that you said to use that list and call people—don’t feel alone. I mean, that applies regardless of whether you’re incarcerated or not, right?

Mark: Right.

Diane: We need connections. That’s the biggest deficit I felt after COVID—it pushed all of us into a place that wasn’t always positive, proving to us that we need each other.

Mark: Exactly. And that’s what I’m working on right now. I’m creating a new relapse prevention plan, and this time I’m actually going to stick to it.

Diane: Is there a moment when you felt that shift in your mindset, from not liking yourself to trying to love yourself again?

Mark: Yeah, it’s been slow going, but I’m really starting to appreciate myself for who I am. I look around sometimes and see people in much worse situations than mine, and I think, “Man, I need to be grateful. I really should love myself; I should appreciate myself.” It’s been a slow process because I’ve felt this way most of my life, but I know I can make my life better.

I just need to surround myself with good, positive people. I go to church, so I’m really trying to reconnect with my spirituality and appreciate myself slowly over time. Just saying to myself, “Look, Mark, this is what God gave you; just go with it. This is who you are. This is what you look like; appreciate what you have.” I’m really grateful to be so active at 48. I mean, I feel great. So that’s what I’m trying to learn—to accept who I am.

Diane: Yeah, I can sense your gratitude. It seems like you have so many good things in your life: you’re with your parents, you have family, you’ve got a home—all that stuff. I’ll be seeing Michael Moore in about an hour. Is there anything you want me to share with him?

Mark: Yes, I just want to say that Michael Moore is a truly inspirational person. He’s been a great friend. I’ve known him since, I think, gosh, 2003. So we’ve been through a lot together. He’s a good man and deserves to be out here. I’ve seen the changes in him; he’s always been there for me. I really appreciate what he has done to make this interview happen today. I’m happy to continue to correspond and share ideas with him; he’s someone who can hold me accountable. He’s really put in the work.

Diane: Yeah, he’s done great. I appreciate him a ton.

Mark: He really loves you guys too. He appreciates you all, talks about you, and is really happy to be part of the program.

Diane: He truly is a light for us; he’s wonderful. Is there anything that I didn’t ask or anything else you want to share?

Mark: I’m just really grateful to be where I am today. I also want to express my deep regret for my actions, especially for the last incident, to the members of the community and to the law enforcement officers who work hard to keep our community safe. I’m truly sorry for what I put them through. They’re out here every day, even though I know a lot of people complain about the noise from the helicopters. Long Beach is a rough city right now; there’s a lot of crime. I was taught not to respect law enforcement because of my experiences in incarceration, but we really need to appreciate these people. Without them, the world would be out of control. I have to show them respect; they’re just doing their jobs. I need to do my part—be a good citizen, pay my taxes, and stop breaking the law.

Diane: Yeah, exactly. Well, you’ve definitely shown your remorse.

Diane: Thank you so much, Mark, for sitting down with us today. I appreciate you.

Mark: I appreciate you too, Diane. Thank you for this time.

Diane: I’d love to hear about what happens in your future. God forbid anything negative happens again, but even if it doesn’t, I’d love for you to keep us updated.

Mark: I sure will. I definitely will. I hope and pray everything works out. Regardless of what happens, I know I’m going to be alright. I’m going to make it through this and improve my life. I’m going to live the best life I can.

Diane: Alright, well, great! Good luck, and please give your mom and dad a hug for me.

Mark: I sure will. Thank you so much.

Diane: No problem. Take care.

Mark: Okay, you too. Take care. Thank you so much.

Diane: Sure. Bye.

Mark: Bye.

What advice would you give to any teenager falling in the wrong direction?