This New City

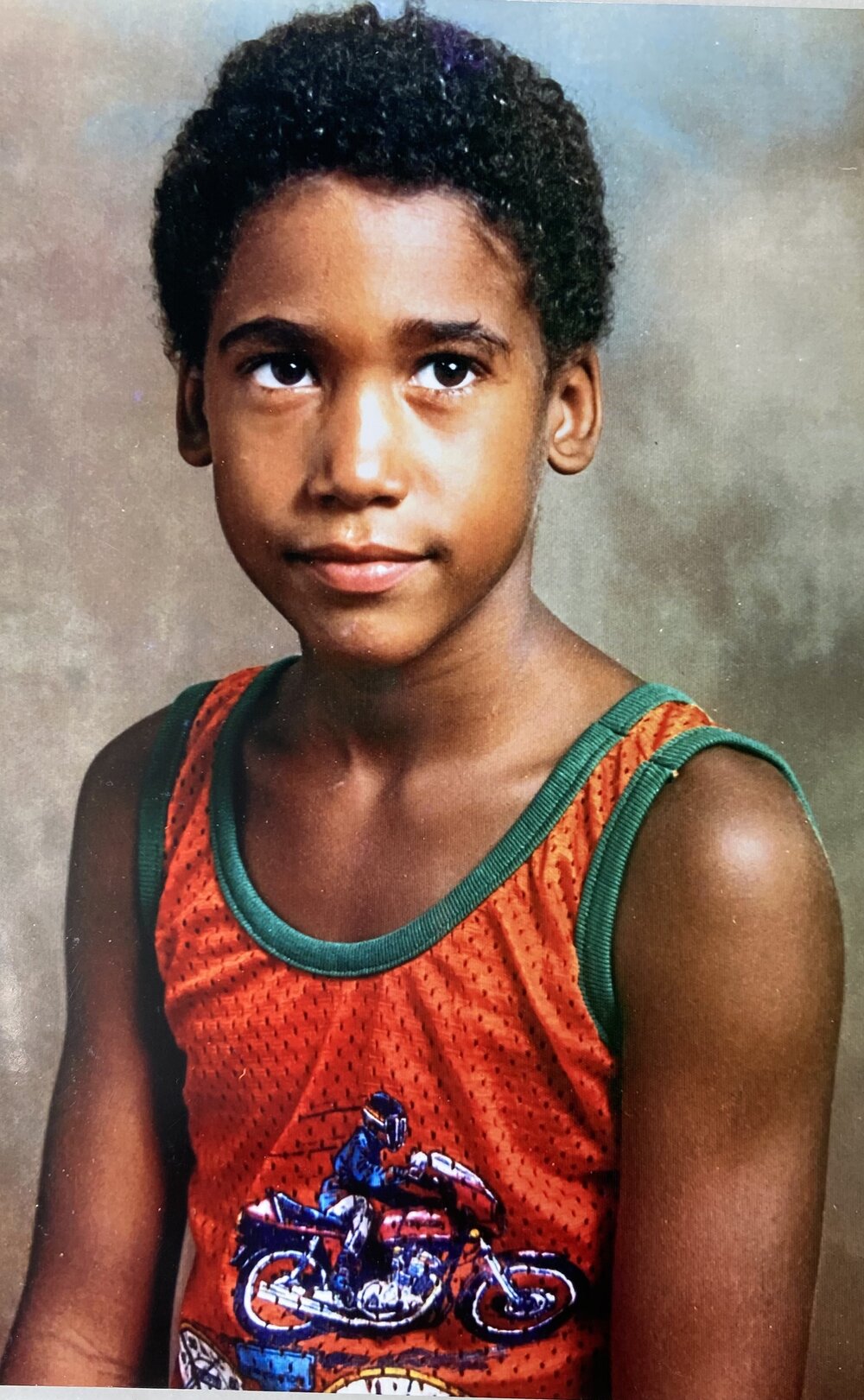

After being in an abusive relationship for a couple of years, my mother decided to leave her boyfriend and move us to Miami, FL. it was 1982. I was overwhelmed by this news. But inwardly, I was happy for her. I would no longer have to see the bruises on her frail body that took days and sometimes weeks to disappear. I would no longer have to hear her frantic cries for him to “STOP.” I was liberated by her courageous choice and a piece of paper–a plane ticket that freed me from feelings of shame and helplessness for not being strong enough to help her. I despised this man–a man empowered by senseless rage and the false notions that led him to believe that beating women made him a man. I was free; we were free.

The district we moved to was called ‘Coconut Grove,’ an ethnic gumbo full of Haitians, Jamaicans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans. I didn’t know anything about the ‘Red-Lining’ of certain neighborhoods, or the ‘Fair Housing Act.’ however, it became immediately clear that I had arrived in what might as well have been a foreign land– a congested metropolis full of poor black and brown people. Amidst the scorching heat and frustrating humidity, vacant alleys and lots were home to heaps of trash and public health violations. Something told me that the general public didn’t care. This was evident by the discarded needles which vastly outnumbered cigarette butts. Still, there was a certain beauty to the palm trees that danced in the warm winds, as the avocados and mangos hung low enough on most trees to reach. And when you breathed in on most days, you could taste the salt in the air—courtesy of the Atlantic coastline which was right around the corner.

Whether day or night, different sized lizards populated the cracks in between the pavement—speeding by you as if just to be seen. And if not them, colorful iguanas peeked down occasionally from phone lines or nearby branches. Gradually I was starting to understand the pace of this new city, which moved methodically to a new urban rhythm.

It didn’t take long for me to see what was going on in this city although I was just nine years old, and oblivious to Columbian Cartels, I was smart enough to know that the constant sirens, overdoses and squad cars meant something—a heroin epidemic. And as the sun set each night, this epidemic became more visible. Consequently, it equaled more crime and cops who tried to restore some sense of balance to this concrete jungle. It was in these early years that I began to see what poverty looked like, but what it felt like as well. Moreover, I understood the damaging effects of the drugs that swept through my neighborhood.

Lord knows I wanted things to be different for me.