Coping Skills

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world indoors for the physical distancing required for safety from infection. Even as restrictions in some places are lifting, here at San Quentin, we are made to shelter-in-place with another adult in a four foot by eight foot by ten foot cell for twenty-two and half to twenty-four hours a day, depending on the rotation of an hour and a half of program time for showers, phone calls, and exercise. Everyday, at least five tiers gets no program.

Imagine being ina bathroom fit for a small apartment. Replace the bathtub with a steel bunkbed. Then you and another adult put some papers, books, and food in there just before being locked inside, where you will spend most if not all of your time together. This person can be a loved one, like a family member or a friend, or a stranger you met over a bowl of mush. That is what it is like living in a cell in San Quentin.

As such, I have compiled a short list of prosocial coping skills necessary for living in such a confined space with another human being, a great idea brought to life by Zoe Mullery, Creative Writing teacher for the William James Association and beyond. These skills can benefit anyone in any living situation, and will go a long way toward survival on the plantation and in the free world, because these skills a transferable.

1] Keep Yourself and your living space clean.

It is known that keeping things clean reduces the chances of infection in tight confines, this is also essential to keep the peace. Adults do not smell good if they do not bathe, so showering must be a priority, and should be done as often as possible also, personal space is at a minimum, so regular cell cleaning is needed, a task that is usually a joint effort. The cleaner you keep yourself and your space, the less likely this social issue will lead to conflict.

2] Be mindful of your cellie.

It is a good practice to make choices with your cellie in mind. A choice that can adversely affect your cellie is a bad idea, even if that choice benefits you in some way. I recommend thinking ahead while keeping any idiosyncrasies your cellie may have in mind all the time. This show of empathy can lead to peaceful cohabitation, especially during a pandemic.

3] Compromise and tolerance are mandatory.

The fact of the matter is, not everyone sees eye-to-eye. Sometimes people have lots of property that occupies this tiny space. Sometimes strong views lead to arguments. Compromise can be the middle ground where a pair can meet and interact. Tolerance is the balm that soothes sore spots during disagreements. Being willing to engage in some give and take and a little tolerance can goa long way towards peace.

4] Find ways to interact with each other,

Since so much time is spent confined in such a small place, especially in these trying times, finding things in common will also help with living peacefully with one another. Find common interests or entertainments or topics of conversation REspect each other’s views and goals, and find ways to help each other. This is a good way to turn a stranger into a friend.

5] Stay out of each other’s way. Interaction with each other only goes so far. People need people; even the recluse needs people to know they do not want to be bothered. That being said, lets face facts: some people just do not get along. It not uncommon for cellies to simply ignore each other. Some people have different views or different goals and objectives in life. Somepeople simply want quiet so they can focus on their work or relax without distractions. The idea in these instances is to respect those differences and needs, and even learn more about the reasons behind those differences and needs so you can better understand the person with whom you share a space. Sometimes it is healthier for youth of you to keep some distance between you, or even to move, in order to solve an incompatibility issue that may arise. This is why it is important to be mindful of one’s cellie, for peace and harmony.

6] Leave the cell as often as possible.

It is true that absence makes the heart grow fonder. Since the space inside a cell is so tiny, itis good to leave your cellie in the cell alone. We call this “having some cell time,” where one can have some solitude in the cell, which is in very short supply these days. From health appointments to going to work, or simply leaving quickly during program times, leaving the cell is the best way to keep out of each other’s way.

7] Entertain yourself.

There will come a time when your cellie will be busy writing personal letters or enjoying their favorite television show or sleeping. Maybe the two of you have decided to ignore one another. At any rate, this is the time to entertain yourself. Find your own things to do to make use of your time that does not involve your cellie, and do so quietly so as not to disturb your cellie.

These seven skills will help anyone cohabitate in an itty bitty living space. Practice these skills daily and your living situation will improve. This is how we maintain our sanity here at San Quentin. Please take good care of yourself and be safe so we can survive this pandemic together.

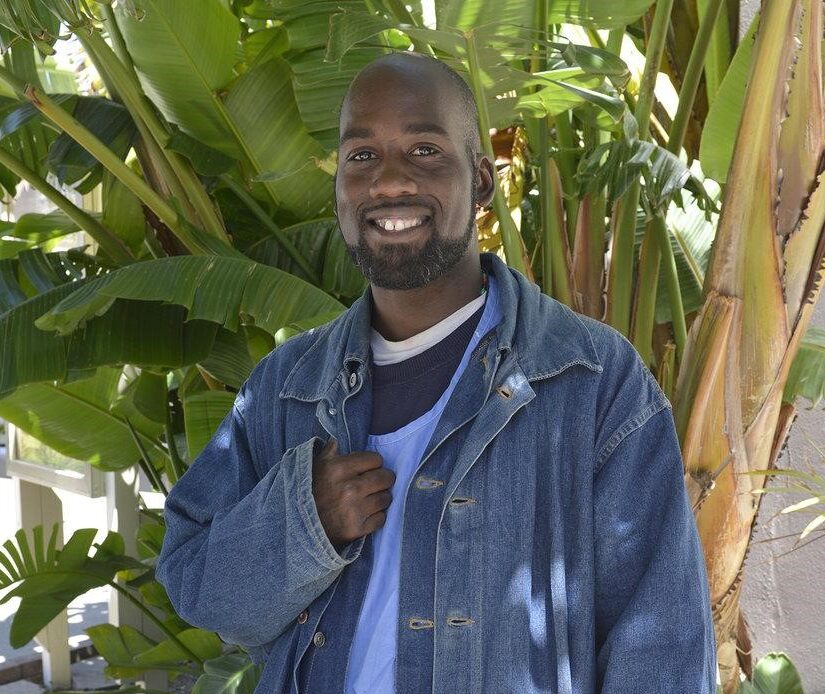

About the author:

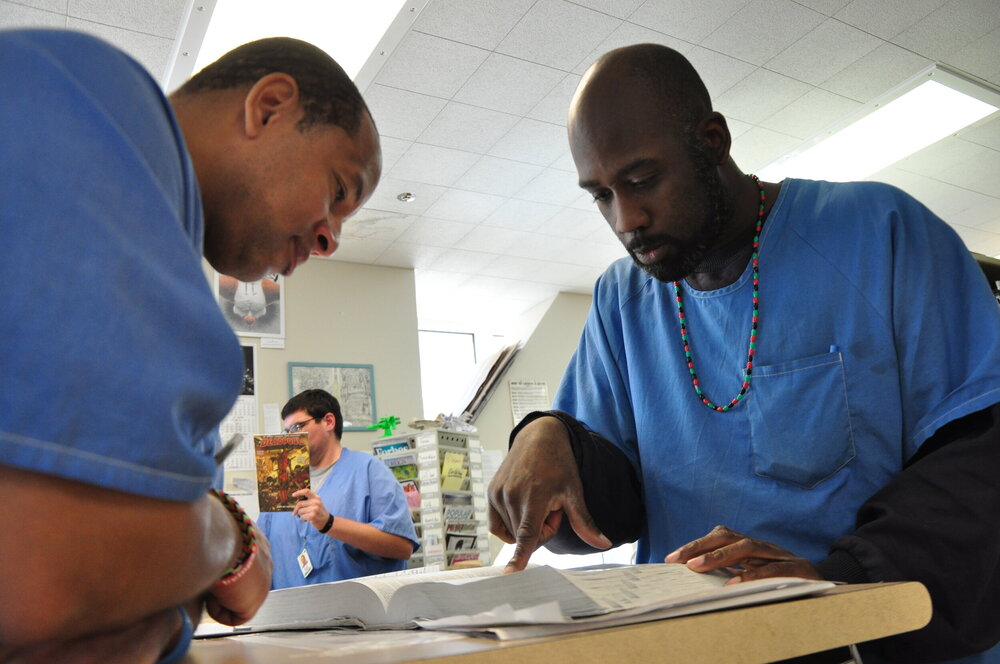

George “Mesro” is a poet, emcee, and graffiti artist currently incarcerated in San Quentin for residential burglary. His first novel Triumph, will be published by Capital Gaines LLC. when he is not playing Dungeons and Dragons, he mentors youth in juvenile hall through his work with The Beat Within, and helps men earn their GEDs at San Quentin.

Untitled

Guess what?

I’m a weirdo.

That’s right, I said it. I’m a weirdo. I like going to school, and I think homework is fun. I like superheroes and robots and starships and dragons. I like seeing octopi change color and shape. I like suns. I eat peanut butter and jelly sandwiches while reading fairy tales. I like all kinds of music, and I play DUngeons and Dragons with my weirdo friends to pass the time.

I’m a weirdo.

Growing up, there was a stigma on this word, weirdo. If you didn’t conform to the code of the streets, you were labeled a weirdo. If you didn’t do what the cool kids did, you were labeled a weirdo. If you spent more time reading than clowning, if you were n=more interested in good grades than a good fight, if you were amused more by cartoons than humiliation, you were labeled a weirdo.

Being a weirdo has its consequences. As a weirdo, this meant I was a target for anyone out to make a name for themselves. Weirdos get bullied and ridiculed. Weirdos are called nerds, dweebs, dorks, geeks and were subject to all manner of torture, such as wedgies, swirlies, purple nurples, melvins, and good old fashioned beatdowns.

Weirdos find themselves in a bind. If a weirdo doesn’t defend themselves, they are subject to more suffering. If a weirdo does defend themselves, the torture escalates.

How do I know this?

I’m a weirdo, that’s how.

So what is a weirdo to do?

The stigma on being a weirdo stems from fear. People are afraid to be themselves, so they don’t get labeled weirdos. The reputation is all that matters, and having the reputation of a weirdo is unacceptable to so many.

Growing up, I was always on the outside looking in. I spent the bulk of my childhood and some of my adult life being “Isaac’s brother.” Now, Isaac is my younger brother, but, because he is not a weirdo, it’s like he’s big brother by eminent domain. “Isaac’s cool and Isaac’s brother is a weirdo” is how the cool kids would always introduce us. I was never included in the fun and games.

Not to say I didn’t have friends, I did. I still do. But my friends are weirdos too. We all had our time spent trying to duck the stigma around being a weirdo. I remember learning Ebonics, and using my rapping skills to avoid beatdowns. I remember committing crimes so people will think I’m cool. I remember avoiding things I loved in favor of what others loved, what I thought others wanted me to love. I started caring more about opinions of others than my own mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing.

And I’m still a weirdo.

Try as I might, I was never really accepted by the cool crowd at large. Catch me playing video games at house parties instead of dry humping on girls. I would rather be in the studio spitting rhymes than pulling heists. I drink apple juice instead of beer. No matter what I did, people saw me the same way. I remember hearing people say “Man, who invited this weirdo?”

So of course this downward spiral of destroyed self esteem and rampant stigma led to incarceration. It beats the alternative, right? The officer that arrested me was ready to shoot me. By that time, this weirdo thought he had nothing to live for, so I didn’t care. Just another weirdo shot by police. Over the years, I realized something:

It’s ok to be a weirdo.

In my estimation, letting someone else live your life for you, letting the opinions of people who don’t know you, push you into trying to fit in with people who don’t want you, these are the behaviors of a clone, a minion, a henchman, a zombie. If being a weirdo means doing what’s right and what makes you happy, then label me a weirdo. If being who I really am, and if who I really am matches what people think I am, means I’m a weirdo, then label me a weirdo. If respecting people for who they are makes me a weirdo, go ahead and label me a weirdo.

Yes, I am a weirdo.

Thank you for noticing.