Click this link to watch a video of Diane’s interview with Floyd.

Watch Video:

Diane: Hi Floyd! It’s nice to see you as a free man!

Floyd: It’s such an experience and such a journey! Good to catch up with you. You seem too busy.

Diane: As a nonprofit owner you get the overwhelming part! I’m just playing catch-up with everybody that’s reaching out.

Floyd: To be honest with you, I still remember being your assistant inside.

Diane: Such fond memories. How long since you were released?

Floyd: It’s been nine months and it’s still a surreal feeling.

Diane: What are some of the things that make it feel surreal?

Floyd: The simple things stand out now, like the choice of food. I’m not ashamed of my weight gain—almost 40 pounds over several months—but I’m working to reduce it. It’s about having the freedom to eat what and how much I want. Another aspect is interacting with people. I always let them know that I’m formerly incarcerated, which often sparks conversations. I haven’t received any negativity, but the surreal feeling hits me when I’m outside on weekends, looking up at the sky. I think to myself, “This is something I couldn’t do in prison.” Seeing Mount Tamalpais and visiting the peak of a hike in Vacaville, where I saw Solano Prison from the other side, reminds me of how far I’ve come.

Diane: That’s beautiful. I feel the same way when I drive past San Quentin on my way to work. It’s amazing to see how expansive the world is compared to the confined space of a prison.

Floyd: So many people take everyday freedoms for granted, like driving. At first, I was scared to drive, but now I’m acclimating. One thing I’d advise others not to lose is the discipline and focus you gain inside. It’s important to maintain that structure and make the most of each day.

Diane: It’s indicative of being stuck in a cell. Outside, there’s so much more going on. But you’ve made the most of your time, which is admirable.

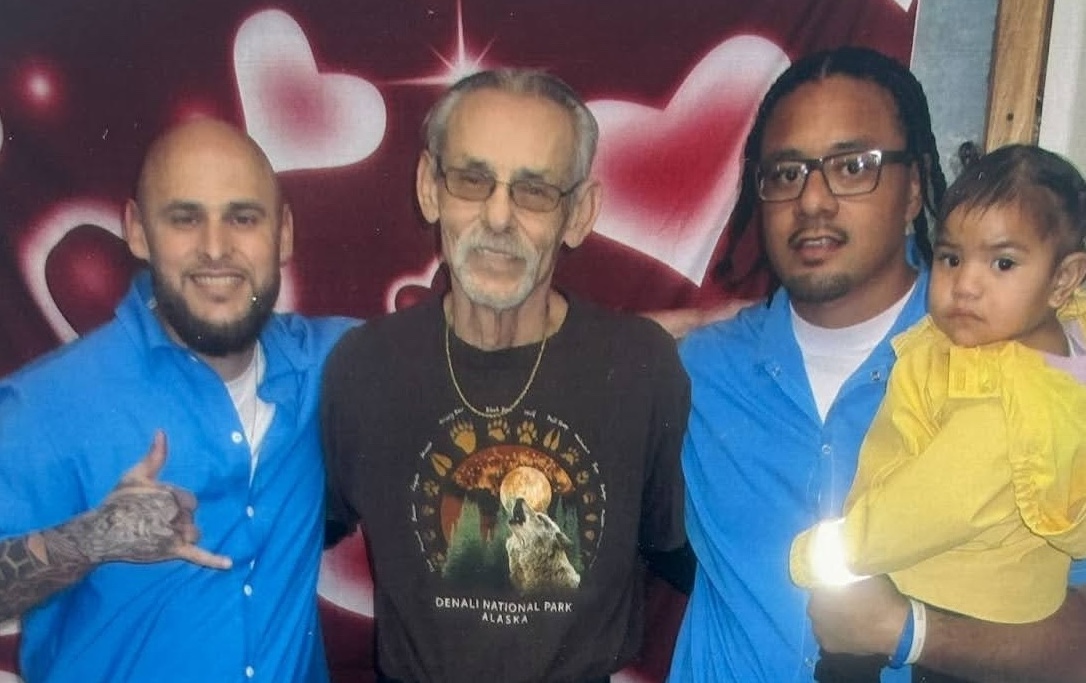

Floyd: Absolutely. For 13 of my 27 years, I was just surviving. I started in a level four prison, and over time, I worked my way down to level two, where I began to transform my life. I was never a predator, but I wasn’t going to be prey either.

Diane: What’s the difference between the prison levels?

Floyd: The California prison system uses a point-based classification. When I entered, 70 points or more placed you in Level Four, the highest security level, which is where I started. Below that is Level Three, where you still operate with a Level Four mindset, adapting your skills. It’s still secured with electric fences. Level Two offers more freedom, with programs like self-help and education. San Quentin, a Level Two facility, has a community feel, almost like a college campus. I also spent time at Soledad, where my transformation began. Level Two is where change really starts, as it’s less institutional and more community-focused. Level One, which I never experienced, includes fire camps and dormitory living.

Diane: Was there a specific moment in your incarceration when you started to rehabilitate?

Floyd: I can pinpoint the moment when things began to change for me. As I mentioned, my 27 years in prison were significant, but it was 2013, after 14 years inside, that marked a turning point. I had just arrived at Soledad, a Level Two facility, where I was introduced to self-help programming. This was new to me since my life had always revolved around violence and crime. I started taking classes like anger management and criminal thinking, and it was in those groups that I first heard a different kind of language—one of responsibility, accountability, and transformation. At that time, in 2013 and 2014, I didn’t fully understand it. I still had a survival mindset and no hope of ever seeing the other side of the prison walls. But my mind began to shift as I absorbed this new language and witnessed people finding happiness in such a bleak place. I decided to invest in that mindset, and that’s when my transformation truly began.

Diane: It’s interesting to hear you separate survival from hope. Most people we work with live for hope, but you were focused on surviving each day.

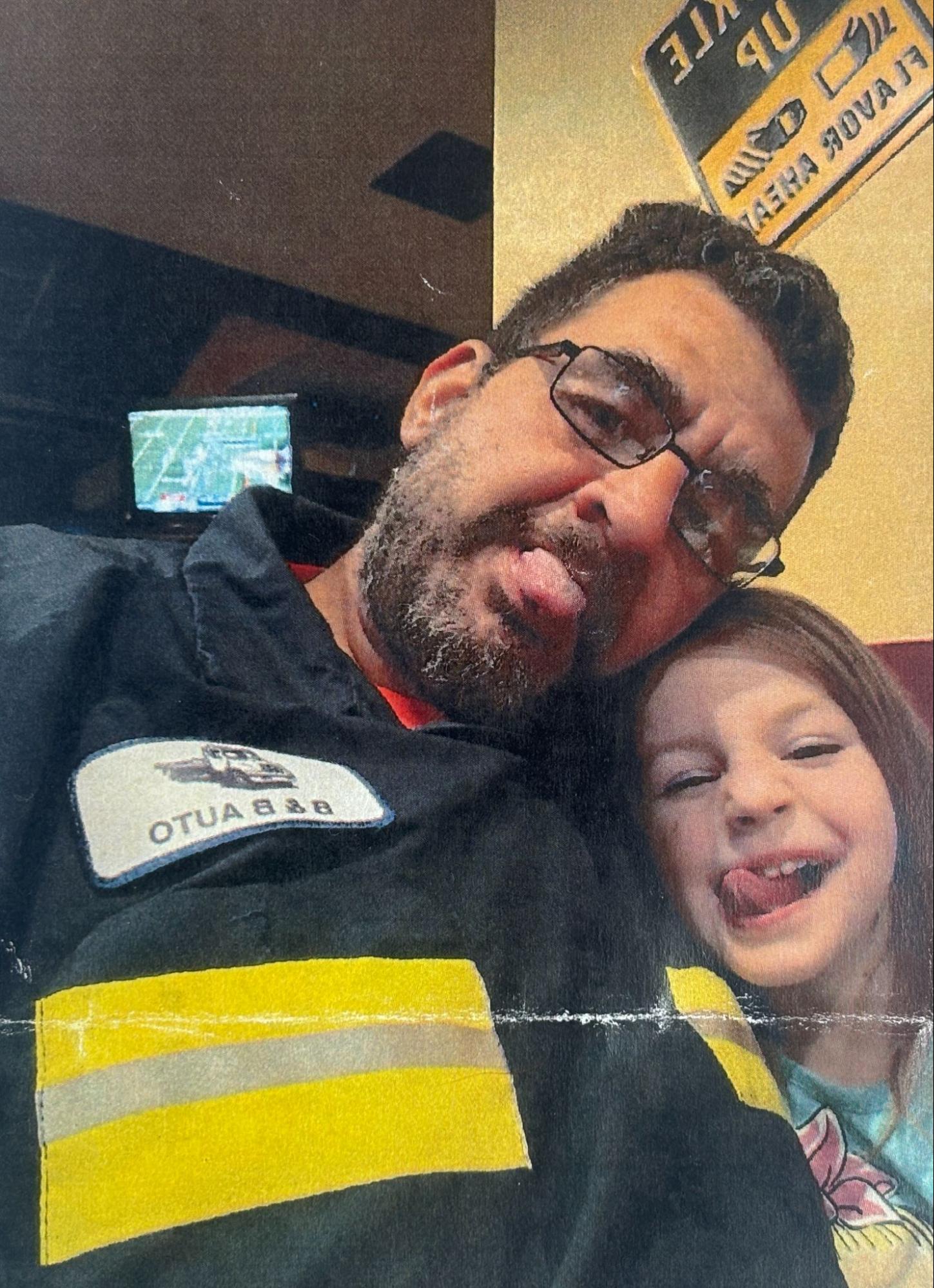

Floyd: To be completely honest, I had what you’d call a hustler’s mentality. I kept myself constantly moving, living from sunup to sundown to keep my mind active. I never became complacent; that’s something I always avoided. Even in my criminal life during the first 13 or 14 years, I was always asking myself how I could help myself. But then something changed in me. I realized I wanted to be remembered for who I became, not for what I did to survive. Let me share something with you—during my first week out, my wife got pregnant, and although our daughter arrived a month early, she’s been thriving ever since.

Diane: Congratulations! How old is she?

Floyd: She’ll be four weeks on Tuesday. She was born weighing five pounds, seven ounces, and is now up to six pounds. Her name is Heaven.

Diane: That’s wonderful. She’s precious. I had a similar experience with my first child, born six weeks early. It sounds like your new life is already full of joy.

Floyd: Yes, I was locked up early, and I mentioned the different security levels—four, three, two, and one. You said you hadn’t heard about the survival mindset and hope in other interviews. While hope is important, there’s also such a thing as false hope—wishing for something that may never come true. But if you hold on to hope, anything is possible. Who am I to crush someone’s dreams? Speaking personally, my hope was always grounded in reality. I knew where I was, where I stood, and where I would go based on my actions. I’ve always thought two steps ahead, even if I didn’t always make the best move. I believe that no matter your background, you can change and transform yourself by changing your mindset and thinking. That’s the only way it happens. However, today’s climate is different, and now it’s a choice. Where I come from, there were racial riots—people reacting to disrespect or drug debts. My reality was survival. I had to ask myself, “Do I have to get involved in this?” For example, a race riot from 2006 came back to haunt me in 2019 when I went before the board. I didn’t live off hope because I was hopeless, but I survived because I had a survival mindset. I engaged myself in different ways—first through criminal activity from 1996 to 2013, and then by realizing that I was the problem. I was responsible for someone losing their life. It wasn’t about what someone else did; it was my thoughts that led me to my actions. This shift took me from denial and blame to accountability and responsibility, and that’s when I could truly talk about change.

Diane: It’s interesting when you talk about hope. I had always associated hope with the possibility of getting out.

Floyd: I think that’s true, especially in San Quentin. Ms. Diane, things are different now. Lifers are actually going home. It used to be that the only way out was in a pine box. When I received a date for my release, it felt like there was no hope. I had never been in prison before, and it was overwhelming. I hope that someone listening to this finds inspiration. It’s about mindset—fixed versus growth. It’s not just about being in prison or being poor; it’s how you relate to your environment. Your mindset determines how you thrive, survive, or decline. Prison was the best thing that ever happened to me because it forced me to become a man, develop character, understand integrity, and find my purpose.

From 2013 until 2014, I had a fixed mindset. I saw things in black and white—everything was either one way or the other. I wasn’t open to challenges, change, or choices. With this mindset, I limited myself: I restricted my social circle and the things I would and wouldn’t do. For example, with a fixed mindset, I might want to go to school because I knew I could earn some time off, but I would give up as soon as things got tough. I didn’t know how to critically think or problem-solve. Early on, I would laugh off getting an incomplete or an F.

By 2014, things changed. I signed up for classes again, but this time I approached them differently. I planned how to structure my schedule so I could get tutored, actually read and internalize the material, and find solutions when I encountered problems. With a growth mindset, I came to believe that there are always multiple solutions to any problem—I just had to find one. I shifted from a “poor me, why me?” mindset to one of “why not me?” I began to see the gray areas in life, where I could go left, right, or keep moving straight—because there were options, and with options, there are choices. My mind expanded, and I realized that there were so many choices available to me. It was up to me to decide.

Critical thinking became key for me. For those who may not understand what critical thinking is, think of it like this: ask yourself why. If you’re still in a criminal mindset, thinking in black and white, you might say, “I’m going to pick up a fix” or “I’m going to get something from Chow.” But why are you doing that? Why continue engaging in what I would now call “today’s stupidity?” With a growth mindset, I began to say, “I don’t need those things anymore. Let me find other ways to build my coping mechanisms.”

One thing I found helpful was reading. Reading is the best way to find a mentor and to escape. With a growth mindset, I started reading different genres and titles—not street novels that glorify the drug trade, but books like Jim Collins’s Good to Great and Great by Choice, or John Maxwell’s books on leadership. I’m not trying to sound perfect or make it seem like I was flawless—I still read The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene, and I think people know about that book. But I balanced it out by reading the Bible too.

When it comes to developing a growth mindset, the first step is to be open to change. You have to let your brain internalize and learn new things so it can expand. That’s what happened to me.

Diane: What prompted you to start thinking critically?

Floyd: The shift had to be in my mindset. I began telling myself that it didn’t have to be this way. Diane, I had never challenged myself in the past to ask why. When I was deep in my criminal behavior, I don’t think I was really thinking—I was just acting on impulse. But when I started asking myself why, I began to respond instead of react. I’ve always thought two moves ahead, but now I was putting context to those thoughts, asking, “What could happen if this happens?” I started adding more depth to my thinking. I realized that I had to go through this process in order to even visualize the possibility of being out of prison, which didn’t fully take shape until around 2018.

Diane: And how long did that continue?

Floyd:I would say it was in 2022. In 2013, I began to make the shift, and by 2014, I still wasn’t thinking about going home or what home would be like today. Instead, I was focused on the legacy I would leave behind—whether I would be remembered as the guy who came here for murder or the guy who got out after changing his life. There are people who go home because they have determined dates. But to answer your question: why did I start thinking critically? Because I wanted more for myself.

Diane: Is there something that made you want more for yourself?

Floyd: I believe people change for two reasons: for someone or for something. For me, she was that someone. I will never forget her question, especially since I was still deep in my criminal behavior at the time. She asked, “Who benefits from the things you do?” She then said, “If the people who claim to care about you contribute to your criminal behavior, do they really care about you?” You know what, Diane? That’s when I stopped sugar-coating things and started thinking critically.

Diane: I was curious about how long you and Vanessa have been together, as you mentioned earlier. It’s great to see that connection. At Humans of San Quentin, we emphasize the importance of human connection. You can’t isolate yourself and expect to rehabilitate and improve on your own. So, how did you meet her?

Floyd: I met her in 2013 at Solano through one of her relatives. It was a bit of a fluke—she had an illegal cell phone, which she used to help me relay a message. As we started talking, we became friends. About five months later, she came to visit. Diane, my wife was the reason I started thinking critically. When I learned I was transferring from Solano, a level three facility, to Soledad, a level two, she had already lined up plans for me. She said, “This is what you’re going to do when you get there.” It was a huge motivator for me—someone cared about me and was so assertive in that care. She helped me by outlining what I needed to do, including signing up for available programs like computer classes. Even though she has her own story, I don’t think she ever wanted less for me, regardless of her own position in life.

Diane: That’s fantastic. And you were open to it, which is wonderful. It’s great that you saw it as a positive influence rather than reacting with resistance or questioning her authority. It’s so important to embrace support and guidance, especially when it comes from a place of care and concern.

Floyd: That’s that growth, Diane.

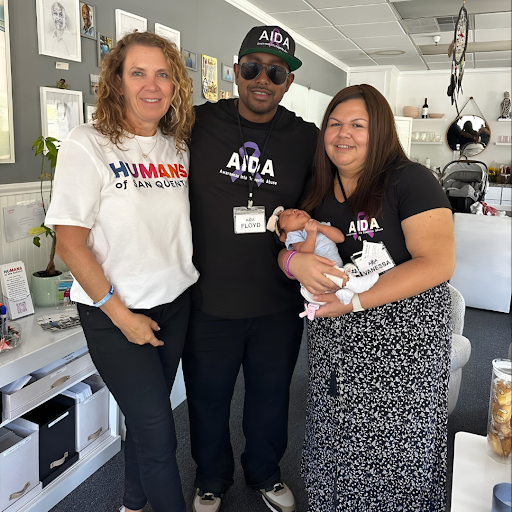

Diane: Speaking of growth, tell me about your non profit AIDA.

Floyd: In 2014, AIDA began as what was then called ILTAG (Inmate Leisure Time Activity Group) at CTF Central Soledad. At the time, I didn’t think much of it; I was just grateful for the opportunity to have these conversations. Over time, I realized that many men had internal issues that they projected onto women, often leading to domestic violence. As the group grew, so did I. The more I learned about myself, the more I was able to help others. In 2019, I’ll never forget being called to the council. To give some context, in 2018 there was significant tension between the Southern Hispanics and the Bulldogs at Soledad, which disrupted our program. Despite the chaos, I was responsible for managing laundry for everyone, regardless of race. During this turmoil, my cellmate was transferred to San Quentin, which I saw as a prestigious place compared to Soledad. He left behind Amy Yamaguchi’s card for me. In the midst of the ongoing conflict, I wrote a brief entry expressing my desire to enroll in her program and attend Father’s Night. Despite the chaos, this was a pivotal moment for me. Diane, can I tell you more about AIDA?

Diane: Yes please! What’s it stand for?

Floyd: AIDA, Awareness into Domestic Abuse.

Diane: How has it been for you? If you’re comfortable sharing, what led you to this point in your life?

Floyd: My journey into AIDA began with my own shortcomings and mistakes. I was an abuser and a perpetrator of domestic violence, stuck in a fixed mindset with black-and-white thinking. I failed to take responsibility for my personal issues—jealousy, insecurity, low self-esteem, and controlling behavior. I allowed these traits to shape my actions and choices, including blaming my partner for an affair and reacting with violence. When I finally took responsibility and acknowledged my own flaws, I decided to join AIDA to help others understand and address their own issues in relationships.My involvement with AIDA began at Soledad, where I started writing to Amy Yamaguchi and eventually got transferred to San Quentin. Despite the challenges, including the impact of COVID-19, ADA continued to grow. I developed a correspondence course into a certificate program, and the program expanded significantly, hosting numerous events despite limited space and resources.

Diane: I remember.

Floyd: As you know, I met you through AIDA, and I was always looking for ways to secure sponsorship and support. The inspiration behind AIDA was my own journey. Today, I’m proud to say that AIDA serves three California institutions in person. Our correspondence course has reached all 32 California prisons, including two women’s prisons, and has expanded to Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Oregon. My current objective is to shift AIDA’s focus from intervention inside institutions to prevention in the community. I want to address psychological abuse and its impact in various settings, including workplaces and schools. My goal is to help people understand how trauma can affect workplace dynamics, contribute to toxic environments, and influence unhealthy relationships. I believe that by raising awareness and providing education, we can prevent these issues from escalating. However, I need the right platforms and support to make this vision a reality.

Diane: What are the primary factors contributing to recidivism, and what changes would you suggest to address these issues within the CDCR system?

Floyd: I want to point out, Diane, that while alcohol and other drugs fluctuate, domestic violence and substance abuse consistently rank as the top two causes of recidivism. These are the leading factors for repeat offenses. I believe it is crucial for the CDCR to mandate that individuals undergo some form of domestic violence intervention to address this issue effectively.

Diane: They need to be exposed to triggering environments, just as they do in prisons in Norway. There, individuals in the beginning are taken back to familiar areas for a few hours to test their responses and graduate to more time with family or people. It doesn’t disrupt the whole system if they slip up. Similarly, individuals should reintegrate into their home environments or work settings to experience real-world challenges and build their resumes, rather than being isolated.

Floyd: People often forget that if we don’t deal with our issues, those issues will resurface in other parts of our lives. An event I never healed from will come back to haunt me, causing rage in situations where it doesn’t belong because I never resolved the original issue. If I don’t know how to have a healthy interpersonal relationship, how am I supposed to manage an intimate relationship? If I haven’t healed from trauma and haven’t been given the tools to interact healthily, then how can I expect to have a healthy relationship? That’s why I think if everyone cleaned up their act, Diane, there wouldn’t be a need for so many prisons.

Diane: Absolutely. When someone gets arrested, it should be more like a crossroads in life. Instead of just sending them to prison, we should ask: What kind of help do they need? Are they dealing with mental health issues that require support? Do they need rehab, domestic violence assistance, or educational resources? Maybe they need financial help. We should determine the right path for them, not just send them to prison.

Floyd: I wanted to make sure I said to you now that I’m very proud of you and what you’ve done with an idea and that you’ve made it so expansive. So, yeah, I’m a fan.

Diane: It was meeting people like you that made all the difference. If you hadn’t trusted us, shared your story, and embraced vulnerability with a growth mindset, we wouldn’t be where we are today. Your openness and belief in this process have built the trust needed for this initiative to succeed. Thanks to people like you, we’re able to hear and amplify these important voices. I truly appreciate you for that.

Floyd: I appreciate you. And is there anything else?

Diane: Let me take a moment to think about that. One thing that comes to mind is this: After all the therapy and work you’ve done to become a better person, there must still be moments when the old Floyd resurfaces, when you feel that surge of anger and think, “I could just hit her right now.” But how do you manage to see things differently now and extinguish that fire before it takes over?

Floyd: So, I really respect you for having the courage to ask that question and address me like that. One thing I always say is that I will forever be an abuser in recovery. What that means is there will always need to be checks and balances. There are a few barriers to overcoming abuse. First, I never want to repeat my past actions. Second, I have a choice now and a new set of coping mechanisms. The mother of my child stood by me during my toughest times. I understand that her feelings and reactions, such as ignoring me, can be very painful, but I am not the same person I used to be. Awareness is key. Here’s the million-dollar insight: self-awareness and emotional intelligence. Self-awareness means being in tune with what’s going on in my body, my thoughts, and my feelings. My emotional intelligence allows me to communicate better.

For example, I can tell her, “Vanessa, it hurts when you ignore me. I feel triggered when you talk to me with your back turned, so I can’t see your face. Can we find a time to sit down and talk about this?” We are committed to communication and have gone to therapy together. Are we perfect? No, but we work through issues by taking deep breaths, spending time outdoors, and finding ways to calm down. If I stay in what I call “madness,” I become stirred up. But I constantly reassure her that she never needs to worry about me being physically abusive. My primary focus is on parole, and I’m not playing any games. I am not the person I was before. She has the right to choose her own path and make her own decisions. It’s up to me to control myself. It’s really about doing the work, what I call “me-search.” This is a term I made up for the process of understanding oneself. If I know what triggers me, I can address it effectively. When I can’t use words, I try to express it in other ways. For example, I might say, “You know, the lighter?”

Diane: Yeah.

Floyd: You’re lighting the wick. Please stop. But, yeah.

Diane: My husband says that to me a lot. He would appreciate you giving me those words to use on him.

Floyd: For me, being spoken to in a condescending manner is both hurtful and triggering. My unmet needs include feeling seen, understood, and loved. Instead of going in circles, I now focus on clearly expressing my feelings. For instance, I might say, “What you just did hurt me. Can we talk about it?” or “I feel neglected and unseen right now. Can we address this?”

Diane: Tell me your job title.

Floyd: I’m the executive director of AIDA.

Diane: There we go! I wanted to hear you say that. How exciting!

Floyd: I mention that I’m still learning and building my network. I’m focused on learning the everyday skills that many people take for granted. I want to improve myself and become better. For instance, I’m interested in public speaking, particularly on topics like overcoming toxic masculinity and abusive mindsets. I want to address how to shift perspectives on abusive relationships and offer new ways of thinking. My goal is to contribute positively to the world, not to be misunderstood as someone with negative intentions.

Diane: Yes, we can easily find talks and events to attend together. There are many people who would benefit from hearing your experiences and insights. It’s just a matter of locating the right opportunities and organizing them. (Shout out to anyone listening who wants to invite Floyd and me to come speak.)

I’ll let you get back to your baby now. Thank you for being so patient with me. And Vanessa, you’re fortunate to have two incredible women in your life.

Floyd: Three with you.

Diane: We’ve got each other’s backs. I’m excited about what we’ll accomplish together. I just need to spend some time identifying where to connect with the right people. And, of course, I’m ready to visit any prisons you need me to.

Floyd: Okay, thank you, Diane

Diane: All right, see you.