Click here to listen to Diane’s interview with Sammy:

Samuel: Hi there.

Diane: Hey, how are you?

Sammy: Oh my god. Awesome.

Diane: What are you doing?

Sammy: I was just playing in the park. The sun is just setting. I’m now on the porch with my feet up, and I’m talking to you. All the sunshine is out today.

Diane: How many days ago were you locked in a cell?

Samuel: 12 days ago.

Diane: Oh my god, you are just beaming.

Samuel: Yes, I am.

Diane: You are a free man. I can’t wait to give you a hug in person.

Samuel: Yeah, right? Because in the prison environment, you can’t!

Diane: How are you adjusting?

Samuel: I’m soaking it all in and just taking it day to day. Last night, they sent me my debit card, and I activated the PIN today. To me, that’s a big step.

Diane: Right, you’re like a natural person now, bank account and everything.

Samuel: Yeah, first bank account ever, and I’m 56. It’s sad, but happy at the same time.

Diane: Let’s start with when you found out you would be released. I’m assuming you went to the board.

Samuel: I went to an early parole board because I qualified for six months of merit time that was taken off my sentence.

Diane: Explain that.

Samuel: There are certain qualifications to qualify for the board to receive time off your sentences and one of them happens to be obtaining a higher education degree. So, I used my master’s degree in professional studies to count toward early release.

Diane: Was this your first time going to a hearing?

Samuel: I had other hearings, but they were for nonviolent offenses. Before, just my papers went, I didn’t have to go physically. This is the first time I went physically before a parole panel.

Diane: So, how were you feeling the morning of your hearing?

Samuel: The morning I went into my hearing, I prepared for it but didn’t prepare for certain things because I didn’t know they would have my life history. I thought they would have my criminal history on file. They asked a question that stumped me for about three seconds, but it’s my life story, so I didn’t feel uncomfortable talking about it. And the question was this: they went back to when the Bureau of Child Welfare took me and my brothers from my single-parent mother’s home, and placed us in a forced shelter. We went through that trauma, and they said: Do you believe that going through that trauma was the reason you turned out the way you turned out as an adult? And I said no, because even though that was traumatic, there was a silver lining there as I got adopted by a very loving, caring Christian family that loved me, nurtured me, supported me, and did their damnedest to raise me just like they raised their other children. And I was the one who made the wrong decisions in the end, not them. I knew right from wrong. And just for some context here, there were three parole commissioners. Two of them didn’t talk towards the end. During the interview, there was this one, and she assisted the district attorney from Orange County of New York. So, I was grilled as if I was on trial again.

Diane: Wow.

Samuel: Yeah. So my thing is, they want to confuse you. They asked the same question eight different ways to see if they could catch you in a lie. But when it’s the truth, it’s never going to change, no matter how many times you ask it or how many different ways you ask it; it’s the truth. And that’s what I stuck with.

Diane: How long was the hearing?

Samuel: About 45 minutes.

Diane: Were your victim’s family there?

Samuel: No. There’s one deceased victim. He needlessly lost his life. The victim’s family wasn’t there. There was no opposition, but it didn’t mean it wasn’t on my conscience. They are always on my conscience because part of what I do today and for everybody else I’ve harmed is to show them that I can only add value to the words I’m sorry by changing the way I was and doing what I’m doing now.

Diane: Living example.

Samuel: Yep, it’s the only way. I always give an example because people sometimes use the words I’m sorry in the wrong way. Suppose I bump into you in the hole. And I turn around and say I’m sorry; that resolves the problem most often. But when it comes to a loved one having their life needlessly taken away, there’s no way I could say sorry for that with words. No way at all. They would say things and probably do things to me that wouldn’t be positive, so I’m showing and proving that what I’m doing today is to help individuals with risk factors in their lives so they don’t make the same bad decisions. And it starts with their thought process. Change their thought processes and choices; they avoid the pitfalls I did when making bad decisions.

Diane: Excellent advice. You’re living a great life already. How did they deliver the news that you were found suitable?

Samuel: First of all, I waited nine days. That was the worst time throughout my whole 23 years of incarceration, waiting those nine days for a decision. All the questions just killed me. On the ninth day, they put me in a bullpen, and I waited on the counseling supervisor. She gave me the envelope and didn’t tell me the answer, and you have to open it in front of her. It used to be that the sergeant used to give you the results, and he’d walk away, but unfortunately, incarcerated individuals harmed themselves when they got negative results. So they changed it. Now, you have to open it in front of a supervising counselor in case you have an adverse reaction to the decision. They’re there to counsel you and help you through those stages. When the envelope is thick, that’s terrible news. When it’s thin, it’s good news. Mine was thick. I was thinking, here we go. I opened it and looked at the first two pages. I didn’t see the answer yet. I got to the last page and saw my release date. The tension just left my body. After smiling so much, I had a cramp on my cheeks for the next two days.

Diane: How long until you were released?

Samuel: Four months. Why? I have no idea. But I’m over that. I’m done with that process there.

Diane: What were your first emotions when you read the line that you were found suitable?

Samuel: It was just a relief of built-up tension.

Diane: How were you feeling the night before you were released?

Samuel: I woke about two o’clock in the morning; I was getting rid of stuff. I wanted to clean everything up. And I had a plan. I would go downstairs to work out, shower, shave, and wait for the officer to pick me up.

Diane: Tell us what your cell was like.

Samuel: It was a little bigger than most cells, eight by eight. I was in eligibility housing, and it was nine by ten and had a window, but it was still confined.

Diane: I bet. What kind of things did you give away?

Samuel: Materialistic things, such as TV, radio, clothes, and specific footwear. Nobody wanted books. Ain’t that a shame? The essential thing in the cell was certain books; they didn’t want them. I emptied everything and waited for the officer to come. I said goodbye to everybody. I looked at the place and walked out.

Diane: Nice. You follow the officer. He writes a home chart. Could you walk us through the day?

Samuel: They take you to this long corridor, upstairs to a draft room, where they process your property. They’re making the paperwork, train fare, money for the gate fee, and other things like my birth certificate, social security card, and undergraduate record. Graduate-level transcripts were in there. I changed my clothes, and then they took us in a van. They were hollering goodbye, and I was gone.

Diane: Where did you go?

Samuel: We go in the state van, and they drop us off at the train station where our loved ones pick us up. My daughter was in traffic, so another guy and his wife let me use their phone to call my daughter. I let her know that I was there. She told me she was in traffic. I said no problem. When Sean heard I was at the train station, he jumped into his truck and picked me up. He called my daughter from the car and said to meet in the office.

Diane: Nice. So what happened when you got out of the car? We can see this on the news, but walk us through it.

Samuel: So I got out of the truck, and the kids from the youth assistance program were instantly screaming. They shouted welcome home, and that melted me. As soon as I went up the steps, I was getting hugs. Then, the tears came down, and my comrades on the inside were there to support me. It was overwhelming. Even people that I didn’t even know were there. Like, hey, we’re a part of this program. We know your struggle. Welcome home. My kids finally showed up, my daughter, my son, his girlfriend, and my other son from Connecticut. They didn’t leave my side.

Diane: Who were the kids that greeted you?

Samuel: They are part of the youth assistance program. Let me be specific, the staff at the high school bring kids to tour the prison. There are three categories of kids, free juvenile delinquents, which means that they’re good kids. They’re doing the right thing. They’re getting good grades and excelling in life, but they live in an environment with risk factors, so they must be educated. Then you have pre-juvenile delinquents where they’re getting in trouble. Maybe they cut class, maybe they smoke something sometimes from marijuana or a drink. They’re getting in trouble, but it hasn’t gotten that serious yet. And then we have juvenile delinquents where some of them have pending court cases, looking towards doing time in juvenile prison or jails. The staff from the high school bring them in so they can get an inside look and experience the rare opportunity to hear our stories. I shared my story. Mainly about being put in the foster care system and going through the process of adoption, and dropping out of my second year in high school. I asked them the question: do they believe marijuana is a gateway drug? And most of them said no. So when I explain my story, how I progressed from drugs, from smoking marijuana, dropping out of high school and dedicating my life to the streets, all the way to experimenting with other dangerous drugs until that one drug that just kicked my rear end, which was heroin, and all the harm that it caused, they related to that. I gave them advice: if I was in their shoes, I would do things differently, and it stuck with them. They applied that advice. So they came back a second time, and then the second time, News 12 was there to report on the program. When the news reporter, Emily Young, interviewed them, they mentioned, “This is our second time here within a month.” So she was like, why? They related my story and how they took it, and they came there that second time to thank me. So that was overwhelming for her. So she asked permission to be there to film my coming home. It was just amazing.

Diane: Oh my god. That’s so special.

Diane: What did you do the rest of the day?

Samuel: We did side interviews. I expressed my gratitude and loyalty to them. I let them know that I’m here. Whenever they need me, I’m here. I told them that I’m never going to forget them, that I will go back to their high school, and I will talk to them as a group or individually. And I’m telling them that promise is a cheat; watch what I do, and you’ll see everything you heard me say within those prison walls; I’m doing it out here.

Diane: What was next?

Samuel: Then I got in the car with my kids and we ate. We just spent the day together laughing, and I looked like a tourist in New York, just looking at everything around me. It was beautiful. I went to my first NA meeting with them. They supported me through that. So it was remarkable.

Diane: What was your first meal?

Samuel: I wanted a spring roll so we went to a place around here. It tasted like they got it from the frozen food section in the supermarket. I was upset. I was more depressed because I was looking forward to a real one. And that didn’t happen, so that was it for the night. I wouldn’t eat anything else. I was drinking juice, and my favorite is ginger ale. Then, the next day, my sister made something I’m still elated about.

Diane: Where did you spend your first night?

Samuel: My first night here, I spent time with my family, and they even sat with me. My son sat in this chair right here for four hours with me, because of issues that he was going through. And we just talked. I was listening because that’s what he wanted. He just needed somebody to listen. We had some laughs and I let him know it’s going to be alright. I told him he already knew the solution. I’m always here to advise, but that you can handle it independently because you’re grown, and I’m here in case you fall. I’m here to catch you in case you fall.

Diane: It’s so nice to hear the confidence and independence you gave him. How’s your living situation?

Samuel: In this house, there are five of us. It’s a three-story home with a basement, first floor, second floor, backyard, and a front porch across the street from a beautiful park in a lovely neighborhood. Everything is just gorgeous.

Diane: And you’re in Ossining, New York, right? In the same town as Sing Sing.

Samuel: Yes, I’m in Ossining.

Diane: What are your next steps?

Samuel: I’m working for a moving company. Tomorrow, I have an interview for a job where I want to work with youth for a program called Both C’s, which is an alternative to a high school program. So I’m looking forward to working with them. They go inside the prison. I know one of the staff members there. He’s retired now, but we used to talk about this inside, and he said if you do get an open date to come home, make sure you call me so I can help you with that process. So that’s what I’m doing tomorrow. Also, I’ll be returning to school. He’s going to help me obtain a doctorate in psychology.

Diane: Have you had any surprises in the last 12 days?

Samuel: The mattress. I woke up with no back pain. In prison, you have these flat mattresses. And even if you get a brand new one, it’ll stay fluffy for two weeks until it goes down. So, even when I put two mattresses on when somebody went home, it was just terrible. So, sleeping on a real bed felt great. It felt great, but I was still on prison time, meaning that I automatically woke up at the time when they usually do the go-around for count at 5:30 a.m.

Diane: Have you seen the stars at night?

Samuel: Here, you see them more because when it gets dark, we’re higher up, we’re far away from the city. So we get a better view of the stars here. But I had that view in Sing Sing. The only difference is that the view there of the stars and the Hudson River came with barbed wire fences, 50-foot walls, and guard towers. Here, it is not like that.

Diane: What was the first thing that you did alone?

Samuel: The first thing I did alone was walk through this neighborhood. I’m not going to say alone because I used WAZE in case I got lost. But I wanted to know exactly where I was and how to get from the main office to here without relying on anybody. My daughter signed up at the gym. She paid for a year’s membership, so she showed me the route that she drives, and I walked that route. I walk there and back as part of the exercise, the pre-workout, so it’s beautiful.

Diane: What else haven’t I asked?

Samuel: I’ll give you a little personal input. I went to see the mother of my kids, and we had that discussion. We said we were always going to be best friends and I let her know where I was. I got to see my granddaughter and sister, and it was just beautiful. I have yet to see my nephew and niece, but that’ll come soon. I am waiting to see my sister from Atlanta. The most emotional part of it really was that during COVID, when my mom passed away, I didn’t get a chance to pay my last respects to her, and God blessed me with the opportunity to be released before Mother’s Day. I went to her tombstone with my son and daughter, and it was draining. My father is there in the same plot. Then there’s a blank spot under their names. That’s for my name. I’ll be buried with them.

Diane: That is so unique. Not many people have a plot of land where they know they’ll be and then to have their parents there. That feels great.

Diane: What have you noticed has been the most significant change in society in the last 23 years?

Samuel: In New York, it’s like a time warp, a scene from The Walking Dead. The synthetic marijuana addiction is a chemical dependency taken to that level, strewn bodies all over the streets laying down anywhere, and I don’t understand. I know addiction, but not at that level. It’s just sad to see, and it really hurt, but that’s what you see in some neighborhoods. The infrastructure has changed, new add-ons and gentrification has kicked in. People are just doing the same thing, they are trying to survive. There are good people still in, and you could tell they’re good people because you could see that they focus was on just getting to where they need to go. You could hear it in their conversations, the laughter, the look on their faces. And it’s just that one part that changes the whole picture with the addiction.

I bumped into an officer that I knew. When he saw me, he said: “Oh, you’re finally released. That’s good. God bless you.” I said thank you. As he was walking away, I said, ” Look, I can wear blue now.” I had on baby blue, the same color as his shirt. He laughed, because you can’t wear blue in any state correctional facility. Yeah, it’s beautiful. So, I’m focused on this journey and will keep you up-to-date every little step of the way. I got a driver’s license. Damn, look, I got my driver’s license! I got a job. And I appreciate everything you’ve done for me and everything you continue to do for me, especially your love and support.

Diane: Oh, you’re so sweet. Of course, I’m a hundred percent here for you. Also, you asked us to send a packet, which we sent out yesterday to one of your friends inside.

Samuel: Okay, thank you.

Diane: I sent him a packet and told him that you recommended us, so without your trust, without you believing in us and being willing to sit down and sit with a camera with me inside, we wouldn’t be here. So, thanks to you, we’re thriving.

Samuel: I wish you had a Humans of New York.

Diane: Well, I’m trying to get there. Yeah, I would love to have a satellite office and work there.

Samuel: I’ll work there because it goes hand in hand with everything I’m doing, and then I’ll get these stories involved. Inside from the prison, there are plenty of good stories. How should I say this correctly? In prison, there’s division among groups of people. Sometimes, it’s split by culture. Sometimes, it’s separated by affiliations. Sometimes, it’s divided by religion, and then sometimes, you have that one group that’s just not in the loop, and they have great stories to tell.

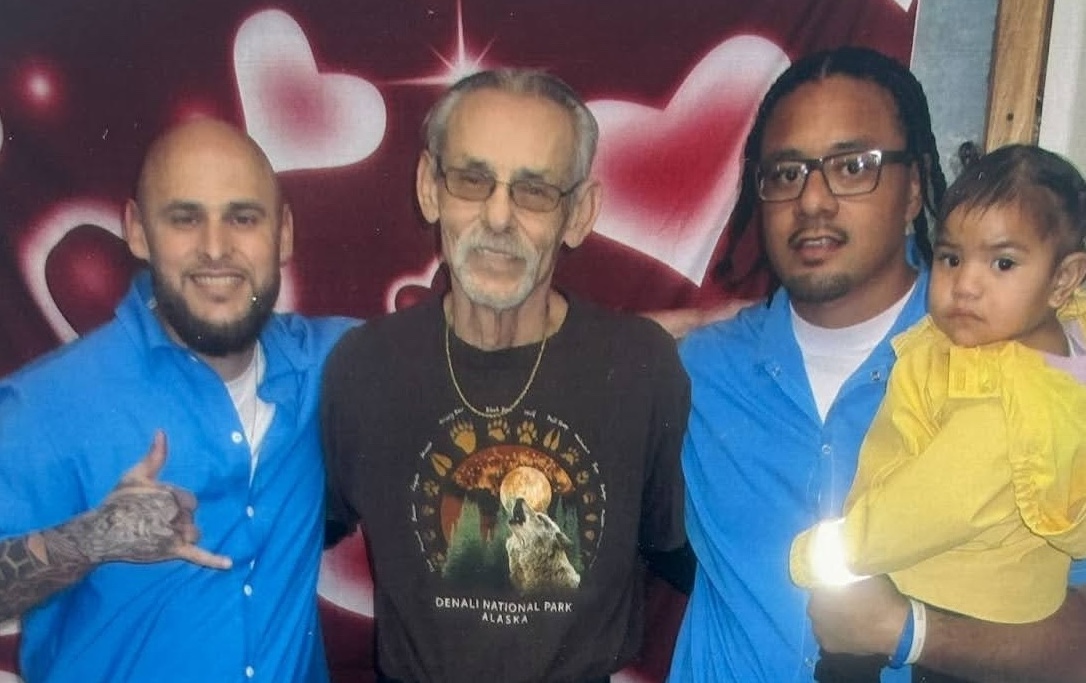

I think I told you this before. I have a son. He’s incarcerated. He has spent 20 years in Greenhaven, and he’s doing fantastic there. He’s enrolled in college, and he’s following my advice. His story is about being the youngest whose father was in prison, and as a young adult, even from teenage years. His story starts there; that’s the other side of the effects of an incarcerated parent’s child. So many stories. So yeah.

Diane: That’s a book in itself right there.

Samuel: Yeah. So, I’ll forward his name and numbers so you can send him a packet. We had this discussion, and he’ll tell you his story. You take it from there yourself. I don’t know if Hector ever wrote. He did a TEDx, and we have a brother-like relationship. That’s how tight we are. He told me his story and practiced it on me before the event. I’ve heard it a dozen times, but when I saw it at the TEDx event, I broke down in tears, especially the part about his mother. Even now, I get choked up. And not too many incarcerated individual stories choked me up like this.

Diane: Is he still inside?

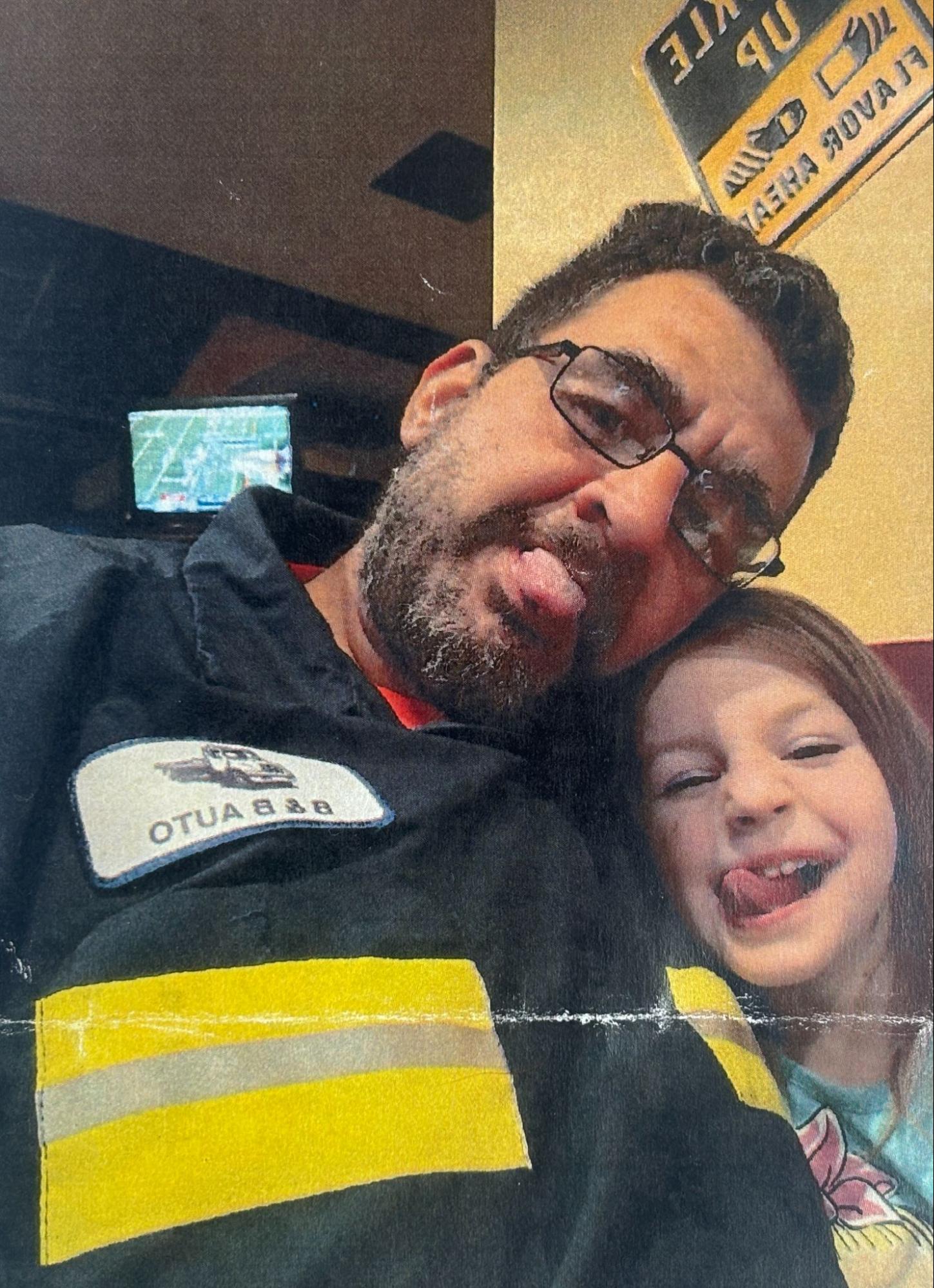

Samuel: No, he just got released yesterday. We welcomed him home. I’m going to send you the videos. He has a six-year-old son, for whom he had trailer visits and conjugal visits, and his son was a product of the system. His son is six years old, and he didn’t know that his father was coming home from prison. He just thought he was going to see his father in prison. When that boy saw him, oh my God, you got to see the smile, the joy. His son never cut his hair for six years. He has a hairstyle that looks like – have you ever seen the Jungle Book, the cartoon, Mowgli?

Diane: Yeah.

Samuel: The Jungle Book, boy, that’s how it was. And he got his first haircut yesterday with his father being there. So we recorded that. We went out to eat. It was beautiful. I’ll send you the videos and pictures so you can see what I’m talking about. I’ll link you two up so you can hear his story.

Diane: Yeah, I’d love that.

Samuel: At the age of 17, they sentenced him to 33 and a half years in prison. So he thought he was dead. And then, his story relates to gang membership and being raised in prison. So he never thought he would see the light of day.

Diane: Oh, I love that. Yeah, I would love to meet him. (To the interns): Do you guys have any questions for Samuel? All right, Judy’s got one. Come on over, Judy.

Judy: Hi, I’m Judy.

Samuel: Hi, Judy.

Judy: I’m doing a project at school right now on reentry, and it is super cool that we can talk to you right now. I was wondering what has been the most challenging part of reentry, like anything that was hard to adjust to or anything that was surprisingly easy to adapt to when you got out?

Samuel: Okay, the most challenging thing was going into the city because I’m from the Five Boroughs of New York City, and I went into my old neighborhood as soon as I got into town. Here’s some context: I exposed myself to chemical dependency with heroin, and then I got clean from 2009 to now. But I wasn’t ready for that moment when I returned because as soon as I went into the city, my nose started dripping, and my stomach started gurgling. But I was going to my first narcotics anonymous meeting so I knew I was going to the right place. But it was hard to go back to that place. The easiest thing is just fitting in. I don’t look out of place out here with the tattoos on my face. People say hi and good morning; they don’t even know me, and I say good morning back. So that’s the easiest part.

Judy: That’s great to hear. Thank you.

Samuel: You’re welcome. Take care.

Judy: You too.

Diane: Apparently, we did an excellent job because I don’t have any more questions for you. You can let me know who you want me to interview, and it’s nice to have a mix of people who are in prison.

Samuel: Right, I mean, struggle is struggle, right? There are different levels of struggle. Some people are not there yet, but they’re striving to get there. And that’s an essential aspect because we must tell the truth. Prison isn’t just about rehabilitation. Not everybody does well at rehabilitation. Some people struggle with that. So it’s good to hear why they’re struggling with that.

Diane: Yeah, there are a lot of people who have a voice, right? You’ve talked to people who’ve been at TEDx and have been on different news things, but it would be nice to have a way to share other voices in other ways.

Samuel: Right, exactly. That allows us to hear ourselves. We don’t get that too much. You’re not going to talk to yourself out in your cell or the yard because you’ll be labeled somebody with mental health issues. But when you’re interviewing us and we’re answering your questions, we get to hear what we’re saying and – wow! Then the questions arise, such as, why did I say that? And then the introspection comes in.

Diane: I’ve never thought of it from that perspective before. How interesting!

Samuel: You provide a sounding board.

Diane: Yeah. I never thought about you guys not being able to hear yourself. How interesting; that’s cool.

Samuel: There are stigmas behind it that we cannot erase, like trust issues. Also, you feel that somebody you’re incarcerated with thinks you’re getting close, and then you break down that door and trust them with something personal that you’re going through. And then they might spread it around. It causes problems, so most people will not open up. And at the end of the day, that voice is lost.

Diane: Yeah. You articulated that so well, I’ve never been able to close that loop for people. So it’s so great to hear you say that.

Samuel: I watched the show. I need to find out what channel it was on. I think it was NYU. Hey, it showed California Corcoran Prison.

Diane: Corcoran, yes.

Samuel: And wow, they got it rough over there compared to New York State Prison. For example, when they get classified, as soon as they walk in, they ask: what gang affiliation are you in? You’re not in the gang, so what’s your race? That’s where you’re going because if you’re white and you go with the blacks, that is an automatic no-no. If you’re Hispanic and you go with the whites, that’s not good. They keep you with your kind, which, if you’re not in a gang, forces you to get in the gang.

Diane: You can’t change your ways because you’re stuck.

Samuel: Right, and once the top gang member tells you, listen, you have to stab this dude – if you don’t stab that dude, they don’t forget about it. You’re going to get it. Seems like there’s more gang activity out there than here.

Diane: Yeah, the Hispanic gangs, the Serranos, and the Norteños, they can’t put them on the yard together, but cells out here are nine by four feet, and they’ve put the guys in there. And there’s another difference with the parole hearings. Here, the victim’s family can be there the whole time.

Samuel: They don’t do that in New York State. In New York State, you can get a parole file review if you put in a motion and see if there’s any opposition before you even go to the board.

Diane: Oh, interesting.

Samuel: Yeah.

Diane: That’s healthy, I mean.

Samuel: Yeah, I agree.

Diane: Interesting.

Samuel: Yeah, but pain and suffering is pain and suffering whether you’re here in New York, California, or across the world in China. Pain and suffering is pain and suffering.

Diane: Yeah. Do you guys have victim-offender dialogues in prison over there?

Samuel: Victim-offender dialogues? No. What they do here is they have this thing called the Apology Bank, and we’re allowed to write to the victims or their families and express remorse. Tell our story of what we’re doing in prison and the part of rehabilitation reentry. They send it off; it goes to Albany, but it doesn’t go straight to the victim. It goes to Albany. From Albany, they send it to the victim or the victim’s family, and you won’t get a response.

Diane: Interesting. Did I tell you about the victim-offender dialogue podcast that we’re starting?

Samuel: No.

Diane: So, I’ll let you go after this. What they do is this: one group that I know of called the HIMSA Collective, and what they do is they work with the victims. Anywhere from two months to two years, they do counseling with them. They help them write a letter to their perpetrator and go back and forth so they can advise both people. And then they’re given eight hours in prison one day to sit down together face to face.

Samuel: Wow, that’s strong.

Diane: It gives me chills to think about that.

Samuel: Yeah, it’s restorative justice. Because you’re bringing the people who were harmed together, the ones that hurt and the ones that received the harm together, and you allow them to work that out to the point where as before the harm was committed so that they couldn’t have closure. That’s remarkable.

Diane: Humans get to see their lives before and what led them to that moment. So, I interviewed four different couples, whom we call couples. What was most challenging for me while doing this podcast is that I advocate for incarcerated people. But some of the women that I have talked to whose perpetrators are in prison – are advocating for their release.

Samuel: Right, okay.

Diane: Me, it’s just been revolutionary, right?

Samuel: Right.

Diane: Michelle was 18 years old and hated that man. And now she’s trying everything she can to get him out of prison. After she sat down and met him, she heard his story and looked at him. In this case, he killed her husband. She listened to his story and what happened and sympathized with him. So yeah, it’s been great.

Samuel: I blame the legal system for that, though. I blame the legal system for that because if we look at it, why are the perpetrator and victim involved in the legal process only when a crime is committed? After that, it’s just lawyers and judges. Right? And then, towards the end, there might be a victim impact statement. But that’s about it. And there’s no closure for anybody.

Diane: Yeah, that’s messed up. I interviewed Alan, who was in San Quentin when I interviewed him. He said he’d told his story twice in his life. The first time he shared what happened that night was with the victim. That was 20 years into his sentence. He had never had a chance to talk about what had happened.. His first time was with the victim in the second trial. That seems wrong.

Samuel: It is. People just carry that harm. Do you know what damage that causes mentally, physically, and emotionally?

Diane: Yeah. All right.

Samuel: Thank you for this opportunity.

Diane: All right. I love you lots. Take care.

Samuel: Take care, alright? Tell everybody I said hi.

Diane: Take care. All right.

Samuel: All right, bye.

This was a good read, thank you.I wish you all the best in your every day walk in this life.May God continue to bless you and keep you, one day at a time. It is just beautiful to see, how the worst circumstances can still turn out to be for the good in the end.Praise God for every new start!