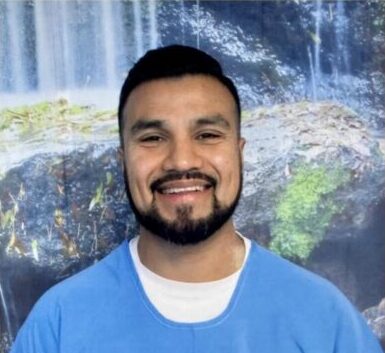

Two of our team members Miguel and Edwin, who live behind the wall, took the initiative to interview men and snail mail them to us. Here we get to find out why.

Why did you start interviewing people?

Edwin: During the Omicron outbreak, I found myself inside West Block feeling tension in the air. It showed in people’s behavior. We were concerned with the uncertainty of the new variant. I found myself tense, confused and angry at the fact that my overnight family visit with loved ones was canceled three separate times. I asked myself, “How do other prisoners feel? What can I do to make a difference, how can I give a voice to the voiceless?” I was also reflecting on the fact that one of my inside team members, Miguel, had just been denied parole. I could see it in his eyes that he was stressed and going through it. I saw how he was hurt. I’ve been denied parole four times, and I know the feeling of being shut down. This is when I decided to invite Miguel to do interviews. Luckily, he agreed. We had volunteer jobs that let us out of our cells, I was a janitor and Miguel was a messenger. Miguel and I immediately became a good team.

Miguel: Living in West Block is a unique experience. It is the dirtiest housing unit with tons of flies and maggots permanently inhabiting the entryway. It is the most overcrowded with double-celled capacity of almost 800 people in one warehouse-style space. Navigating through the noise and chaos is a constant challenge. The ever-shifting conditions of the quarantine lockdown had ratcheted up the already stressful environment. We all wondered if we would get sick living only 18 inches apart. Will someone lose it, break mentally, or get violent? Will I get to call my family? Will I get to shower? Will I be able to leave this cell? Will I lose my property and only pictures of my family? What will happen next? It’s interesting to hear Edwin’s perspective on this collaboration. I wholeheartedly appreciate his care for me in a difficult time, and yet I didn’t see it the way he did. I was focused on writing and positive activities as I processed my emotions about my parole denial. I agreed to take the initiative with him because I saw he was serious about journalism, rehabilitation, and work. He set interview times, came to my cell to wake me up and kept on me about the next interview. I am a person that has a million ideas and can work on many at once, yet follow-through and actual completion can be a challenge. Where I struggle, Edwin has strength. The funniest thing about our partnership is that I did not like him at all when we first met! He has this air which is annoying. He often says, “I’m blunt,” to soften his directness and ability to cut through issues. If you do not know him this can be off-putting- it was to me- but once you get to know him it comes across as a real desire to move an objective forward. I appreciate this for real. I saw this as an opportunity to do something meaningful. It reflected on I want to be in this life. I wanted to act, under these conditions, because this kind of response truly gives my life meaning. To live my values, the ones I talk about, under pressure and no matter what- this gives me a sense of worth and validation that I could not have otherwise. This makes my failures and shortcomings worthwhile. For this I am the most grateful to those we interview, to HoSQ, and to Edwin.

What have you learned through these interviews?

Edwin: It has brought enlightenment to see into a world full of compassion, understanding and mainly empathy. When I have thought I have it bad, I saw someone else who has it worse, and they too want to be heard. It has taught me that if we work together inside these prison walls in a humane way, the sky shall not be the limit. Collectively we can accomplish just about anything in a prosocial way. It doesn’t matter your race or background or our prior social status. We are all humans who have fallen short of making the right choices. Each interviewee taught me something good about life, even the youngest ones. The reason why we took the approach to interview instead of having them write their stories and submit it by mail, was due to the lockdown. People get stressed out, angry and confused about this situation. We wanted to break through all of the negativity by creating a space for us all to socialize and to be heard during these hard times. People in prison can put a mask on and want to be seen as hard core, bad ass or at least not weak. We wanted to break that stigma. To show ourselves differently to the outside world.

Miguel: As often happens, Edwin speaks with positivity and clarity and I agree. He summed it up best when he said, “Everyone that we interviewed taught me something good about life, even the youngest ones.” I concur! I feel humbled when people agree to bare their soul to us, to trust us with their life experiences, wisdom. Then, entrust us with the responsibility to share their story in a real and caring way. Sandia Dirks, a journalistic mentor, taught me about not merely being a story-taker in seeking to be a storyteller. I always remember this as I interview another human being. I remember positionality and the relative perspective we can all have. This never excuses our actions, wrongdoing, or the harm we cause others, but there is a value to be seen in the lessons people choose to take from their actions. In the latest quarantine lockdown, I saw people that were in the exact same position as me, people that I could bear witness for, people that I could learn from. Edwin was the first one on this list.

Do you prepare for your interviews?

No. We pick our questions right there, spur of the moment. We refer to it as, “Keep it real and simple.” We naturally had this cool rhythm and vibe. Without thinking about it we were just on the same page. We wanted the real deal, the human side. From childhood traumas, to the impact of gun violence, and mainly we aim at highlighting the transformation of every single person.

Did you face any barriers?

Time. We were only out of our cells for 90 minutes a day. We had to interview, call families, workout and shower. Then, we had to ask people to give up their time for us. We also interviewed people through the bars of their cells. We tried to write and type standing up, but eventually we would sit on the bars outside their cell.

Is there anything else you want to share?

To us your voice matters. We personally think that when you engage in a conversation with someone they are more open to just say it how it is. We try to bring that genuine side out. Typically people who write in are more concerned about the grammar, spelling, or saying the “right” thing, as they are trying to pour out their thoughts. These can be discouraging. We are grateful to have the opportunity to be of service in what is a challenging environment, to be of service to those who may not yet have their humanity shown to the world.