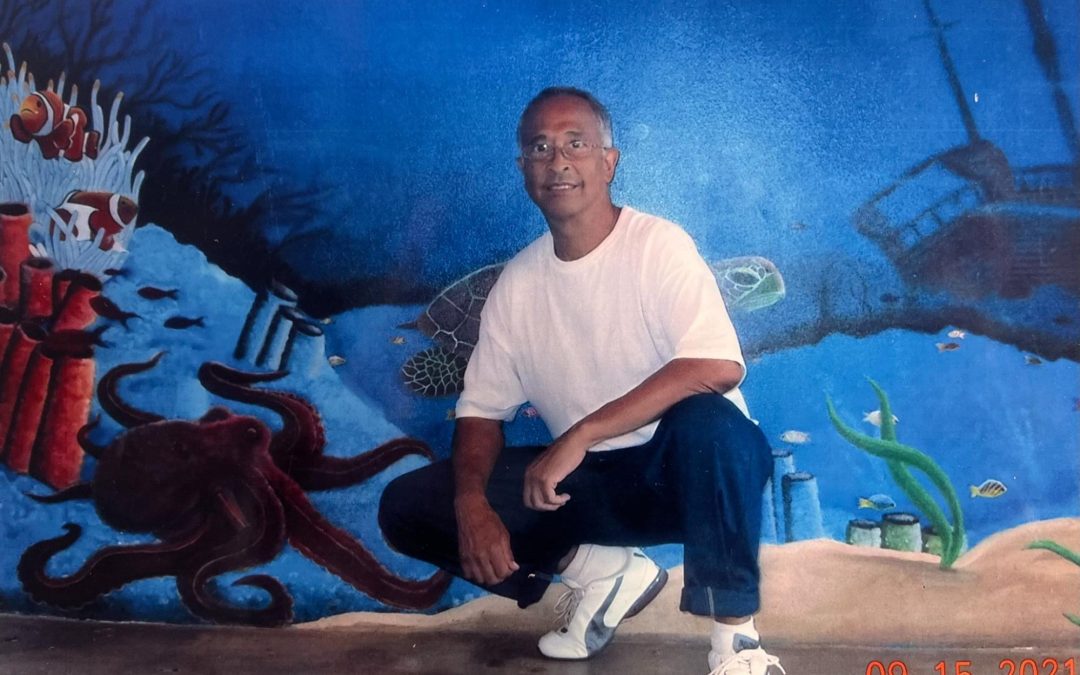

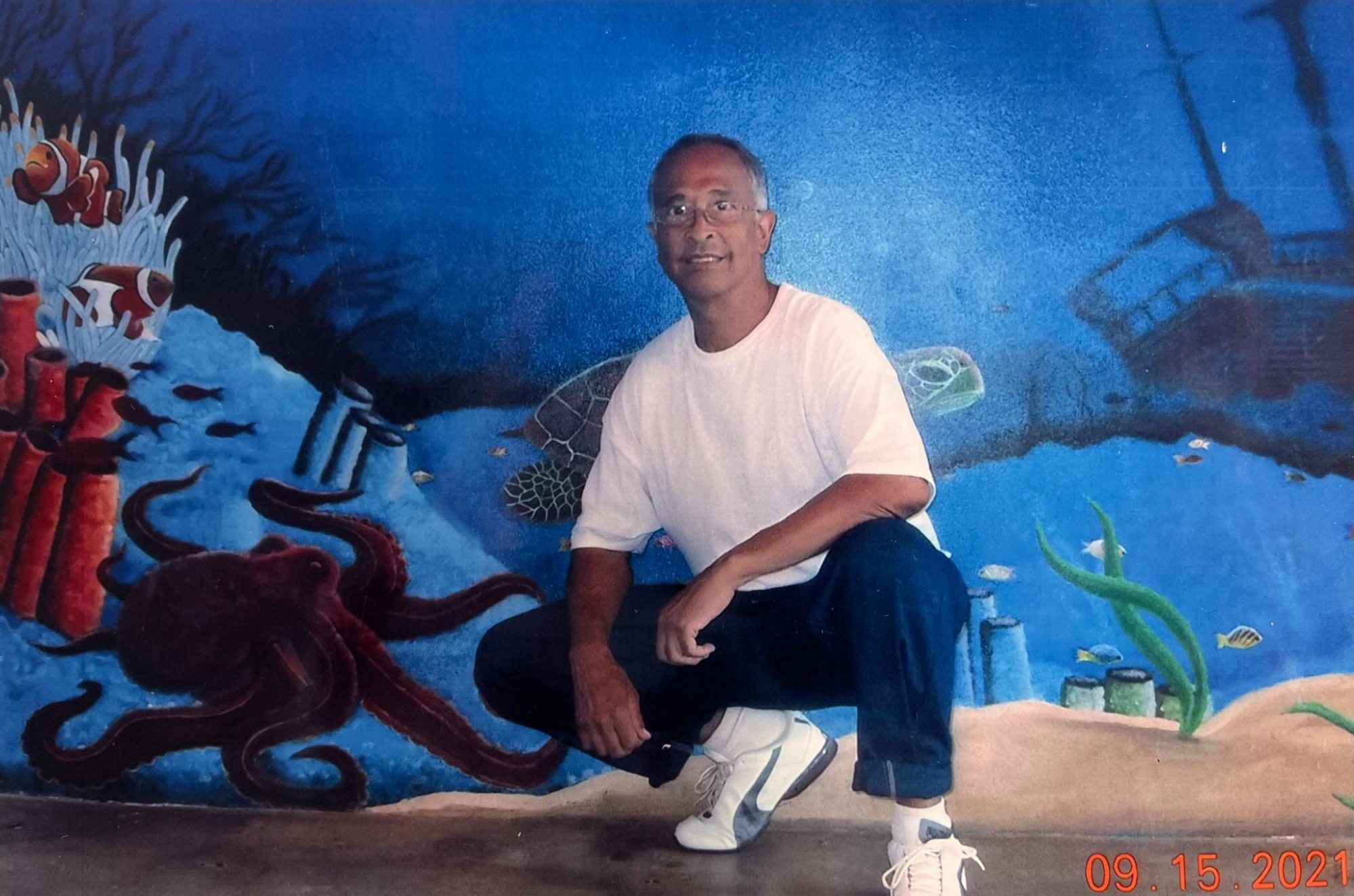

Ramon, 63

Incarcerated: 27 years

Housed: Donovan Correctional Facility, San Diego, California

The life of a death-row prisoner is harsh, restrictive, isolated, and lonely. So moving out into the mainline environment after 24 years of death row continues to shock and amaze me, most so because I had never been to prison before so I never knew what mainline had to offer. So my experience is vastly more astonishing than someone who’s been in and out of institutions. Tidbits sneak up on me from time to time where I say to myself, “I can’t believe I’m doing this right now.” The decades locked away had conditioned me to not expect certain things and be content with nothing. Now the ice in my heart has started to thaw and sunshine begins to brighten each day. It’s pretty sunny now! I continue to marvel at the vast changes my transfer has provided me, like walking on grass for the first time in decades. I find myself in the dirt with a blossoming ‘garden’ of sorts enjoying touching the grass, soil, and pulling weeds. Who would’ve known? We have specific tables each ethnic group hangs out at, but my table has huge mint plant patches accompanied by a few green onions, bell peppers, jalapeños, flowers, and other random seeds I wanted to see if they would germinate. No other table compares, it’s the talk of the yard. Other inmates stop by to check it out while officers and free-staff make positive comments too. Maybe in my cynical death-row way of thinking someone will be malicious or vindictive and stomp my little garden to oblivion, but I have gotten a great deal of enjoyment and satisfaction creating and nurturing something beautiful and unique that previously never existed. Death row consists only of steel and concrete, and the only dirt available is the dust that accumulates in the cracks of the cement when the wind blows. Now I have four acres of land at my fingertips that helps me pacify my days.

Death row is very punitive and restrictive. I have seen guys written up for ‘dangerous contraband’ for things as harmless as a paper clip, a metal envelope clasp, or a wooden ruler with a metal guide strip. Imagine my disbelief and awe when I’m outside swinging an aluminum bat at a baseball game. How about using a shovel and rake to tend to my garden? Real solid implements forged from sharpened steel. Is this legal? I always felt like I was doing something wrong. I recently worked on a ladder the other day, something a death row person would NEVER be allowed around let alone touch. There’s always some apprehension about handling ‘tools’ around my wrists every time I left the cell. I haven’t touched a set of cuffs for the last three years. Imagine how liberating that now feels. My existence now is just normal everyday life here without the stress, worry, harassment. I have interactions where some officers and free-staff call me Ramon instead of Inmate Rogers. I am considered more of a human in my new environment treated with a semblance of respect and dignity. I jumped on an electric golf cart the other day to the other side of the yard to deliver supplies and part of me felt like I was making the great escape. Being condemned never in my thoughts would I imagine being able to do these things that I do now. On death row our day is done by noon, we are locked inside the remainder of the day. Someone asked what I was doing in the middle of the yard staring skyward. It had been decades since I saw the night sky, the moon and stars, to smell the night air, to hear the subtle cadence of nocturnal creatures and who would ever tire of the majesty and spectacular hues of those regal sunsets? Nature has its own unique and unmatched awe and beauty but all that has been taken away from the life of a condemned. Words cannot express how amazing and stunning the world is viewed through renewed eyes after being locked away from it for decades. It’s like a whole new world I’ve had the privilege to be invited into. I’m thankful for the invitation back into reality. As this uncertain journey continues my eyes will be opened wider each day, not taking anything for granted.

I’m sure you are aware that me and the other death row inmates who left on the pilot transfer program are still classified as condemned inmates. The amenities, privileges, freedoms, and programs are far superior but we are still death-row inmates just living in a different institution. Many inmates and staff think we will be off death row and no longer condemned, but that’s not true. Technically we are out of San Quentin, but our classification hasn’t changed.