I wanted to help my mother and plead for my father to stop. Yet, my legs wouldn’t move and sound evaded my lips. As I stand there petrified, my older brother rushes to our mother’s aid, grabbing our father’s arm, begging him to stop. My brother had done what I had wanted. But I was too afraid. My brother was a hero to me. This chaotic scenery plays out before me through a veil of watery curtains. My legs finally move, but in the opposite direction, as I retreat into the closet nearby. I sit there crying into my lap and hoping that all this is simply a nightmare. I tell myself that I am a coward, that I could have helped. The fear inside anchors me down and paralyzes all my motor functions. In the time I fall asleep and when I wake up, the nightmare seems to have ended.

The next day no one spoke of what happened the night before. I watch as my father packs his things and walks right out the door never saying a word. There is a sense of relief, confusion, and sadness. All I hear from my mother is that my no good father is leaving me and that he isn’t coming back.

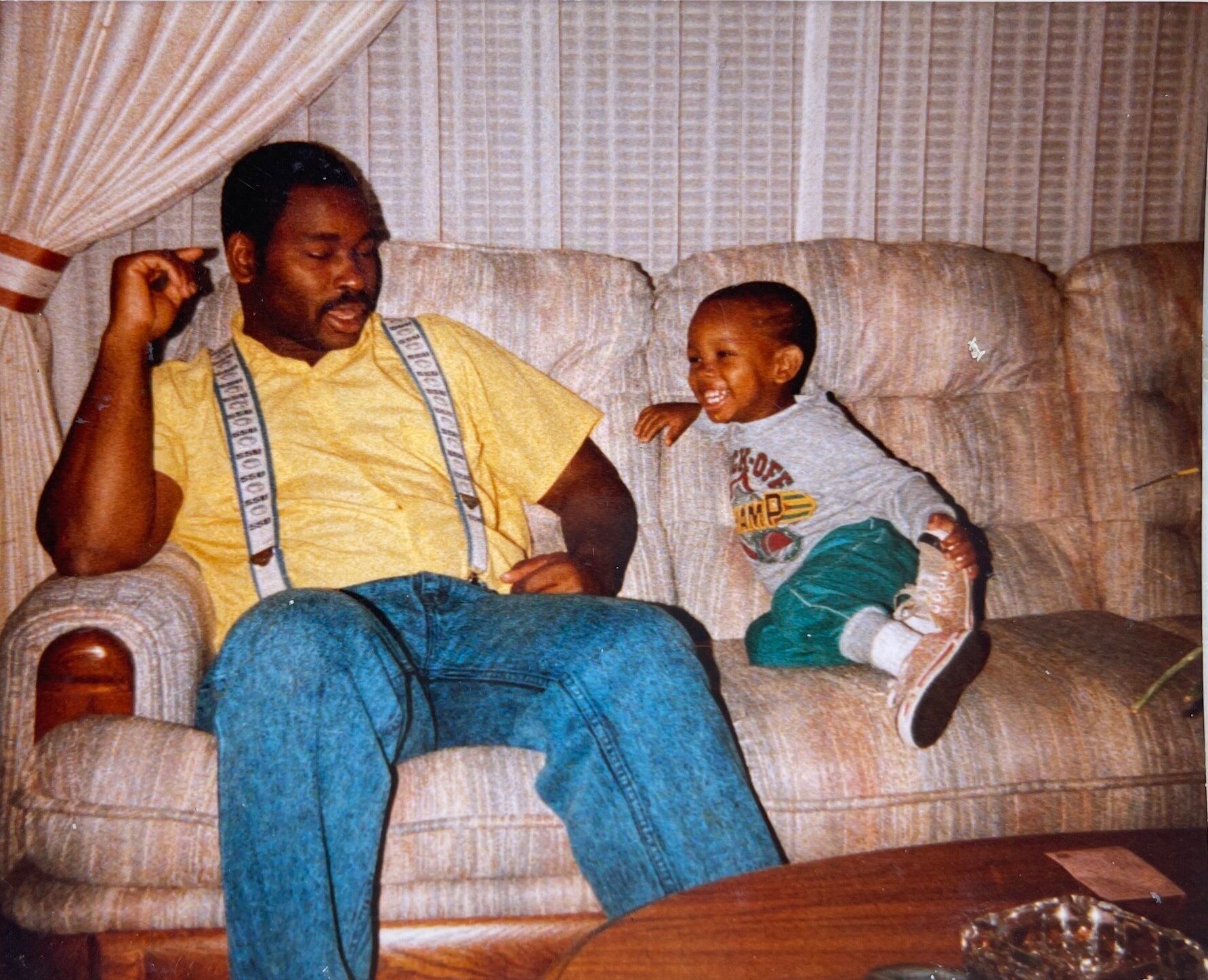

In the following years, my family moved twice and I was left wondering what man my mother happened to be dating would become my step father. I watched as my mother had relationships with multiple men, and how each one tried to bribe me for my acceptance. I saw the power of the manipulative attitude I had come to embrace. It rewarded me with money and gifts. In the next couple of years I would rarely see my father and his side of the family. My small world consisted of only a handful of people. They were my two brothers, my mother, her boyfriend (s), and I. This small world grew when I moved to San Lorenzo.

I remember that first day at Bohannon Middle School as any other day, I had been the new kid so many times that the fear was familiar. It definitely wasn’t my first time feeling awkward and shy. A year went by and I started to feel stable at this new home. For once in my life I would stay in a home for more than four years. It was in this town that I would make life-long friends and make a connection with others that I never had before. It was here that I took the reins on my life. I spent more time with my friends than anyone else. With them I felt loved and valued. I felt like I belonged. The time I spent with my friends was an escape for me from what was really going on in my family. I was embarrassed to bring my friends over because, on occasion, my mother would be right there giving me the death stare. My friends feared my mother, but they would never know the fear and pain I kept deep inside. I was scared to let them know. I was scared to lose them. I was scared to be vulnerable. I wore a mask that was only visible to myself. No one else knew when it was on, or off.

The life I chose to live has been a mystery to many. For I was living a double life. One moment I was the morally upright person, playing out all the positive characteristics my role models had taught me. People around me admired and adored me for my positive acts. On paper I excelled in academics and it seemed that my parents’ dream for me would come true. What my parents were unaware of was the darker side of me. A more rebellious side that was only being compliant so that I could get what I wanted. Because of the lack of communication between us, my mother could never tell what was on my mind. All she saw were the grades I brought home. Grades were merely a tool for me to escape my mother’s ridicule. Only those closest to me saw glimpses of this darker being.

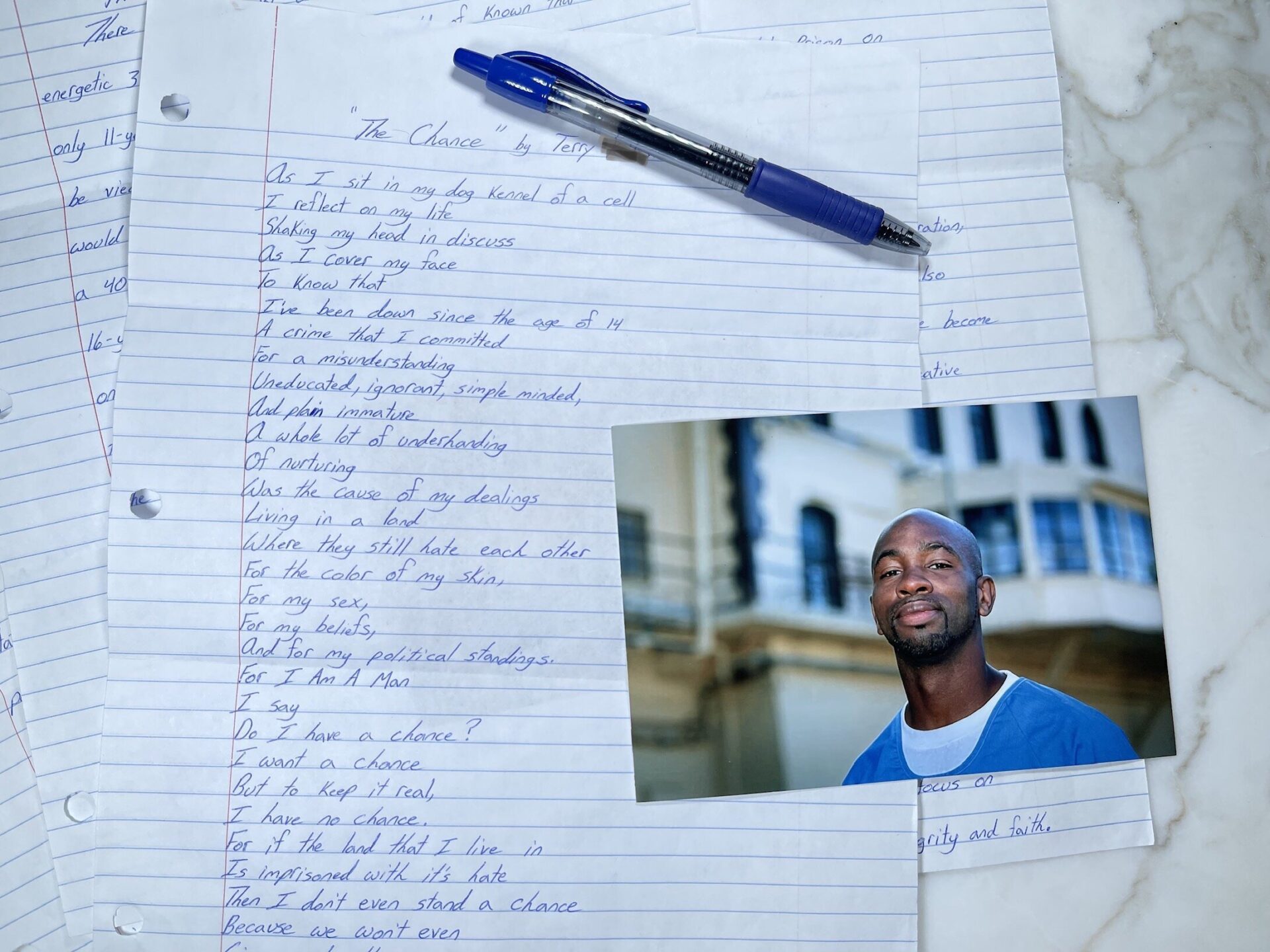

My right hand seems to be possessed by an unknown entity as I tried to write the next few lines. There is a voice inside me that tells me to stop. A most sinister voice that wants to prevent me from healing and accepting the truth. I struggle to continue writing about the birth of such darkness. There is a clear connection between my traumas and the choices I make. The inner demon deep in my internal inferno cries out in pain every time I express emotions. The two sides of me that have been battling for years lead to constant conflict in my values, goals, and beliefs. I stop the writing process and sit in meditation. With eyes closed, I watch as thoughts and feelings arise and fade away. A light of clarity shines through my mind as the demon inside me reveals it’s true form.

There is a young boy no older than nine years old cowering in a closet. The closer I approach the boy the more I notice an aura of anger, fear, and pain emanating in this empty space. Standing before the boy, he glares at me like a hungry wolf, I kneel down to meet his gaze. I see all the struggles he’s been through in those eyes, all the pain. This poor child has been with me for decades, and in moments of stress he lashes out at the world. Words flow from my mouth as I whisper, “What happened in your life was not okay, but you’re going to make it and know that I love you.” With open arms I embrace the pain ridden child with compassion. The last thing I hear are his soft cries and the touch of warm tears on my shoulder. All that hostile aura dissipates in an instant. Bringing my consciousness back to the present moment I notice the tears flowing, and my entire being radiates with peace. With a most invigorating life energy the pen begins to flow again.

In high school I did anything to gain my friends’ acceptance and love. At times it came at the expense of hurting others, whether it was physical fights that I justified my way through or hurtful words that I inflicted upon others. All I was concerned with was how to get others to notice me. My academics were satisfactory and because of that I gave myself permission to act out. I manipulated people to do what I wanted them to do, I used violence as a way to show my friends that I would do anything for them. In my mind I was their protector, not that cowardly kid hiding in a closet. I told myself this was my time to be the hero. Over time, my aggressive behavior became a habit. I became a bully. My aggression gave me the control I always desired, so I latched onto it as a primary tool to assert myself in uncomfortable situations. I had become what I believed I hated the most. Drunk with power and delusion, I lost my rationale. My ego was inflated by praises and affection that others heaped upon me. Unable to contain my selfish ego, I allowed it to run rampant. By the time I became a senior I thought I was the shit and did anything to prove it.

In 2007, I left home to go to college and lived in a home filled with friends. I was genuinely happy at this time in my life. I used every celebratory event as an excuse to drink and go wild. It got to the point where drinking became a norm every weekend. My problem was that I wanted to stand out in everything I did. So I chose to drink the most and to be the loudest. Yes, even in my college years, the child in me from years past was still making the decisions.

So I continued harming those around me with little or no awareness of their feelings. Alcohol gave me the confidence I lacked. It was another tool I used to gain what I desired. Alcohol and my aggression went hand in hand. It was easy to blame my belligerent acts on the booze. In college, I saw alcohol and drugs as a way to gain people’s acceptance. In times of alcohol-induced delusions, I felt invincible, like I was on top of the world. Anyone who challenged me or those I loved would be met with violence. In college I was involved in several fights. Fights in which I used the justification that I was only protecting my friends. My view became even more distorted when I was drunk. I perceived threats where there were done.

In 2009, my little cousin was beaten to death at a party that I told him I would not attend the night before this event. I told him I had work early in the morning. Before college our relationship was as tight as brothers, but it deteriorated over time due to my actions and a resulting lack of communication. I blamed myself for not being there, as the pain, guilt, and shame surrounded my life. I could not protect my own cousin in his time of need. What was more disheartening was the fact I never got to tell him how much I loved him, and how sorry I was for disappointing him. I was a coward, just like so many years ago. I hated this feeling and dove deeper into my addiction. I spoke little about my cousin and did not want to be around his family. I felt intense shame and guilt around them. The more I used substances the less I felt these unpleasant feelings. I could not picture enjoying life as much as I did without substances. My addiction was at an all-time high after graduating college. My success in life once again was a justification for my behaviors. Behaviors that would lead to a lifetime of suffering for so many people, and ultimately a tragic loss of life.

December 20th 2012 was a day for celebration and joy. It was my girlfriend’s and friends’ graduation. We all lived under one roof. The twelve of us were preparing for a celebratory day. I woke up that morning with excitement and anticipation. This day was also the day I was to again meet with my girlfriend’s parents. To deal with my anxiety I took a xanax pill and watered it down with a couple of beers. Filled with a false sense of confidence and bravado, I put on that mask with the belief that the intoxicants would somehow help me impress her parents.

As the day progressed, I drank more and more. The joy was everlasting for me and I did not want it to end. I had gone from partying at home, to going downtown bar hopping. At the after party, things got out of control. My friend and a fellow party goer got into an argument and had to be separated. In this moment I was triggered to do what I had done before to protect my friends, at least that’s what I told myself. All the emotions I was running from as a child came to mind. In response to such unpleasantness in a now-hostile environment, I chose to take control of the situation by using violence. Being inebriated only helped fuel the anger that masked my discomfort. My mind concocted a threat, as thoughts of hostility ran rampant. Compelled by those thoughts and the brewing, unpleasant emotions, I decided to take it upon myself to physically assault two people and murder another.

Suddenly, the pen in my hand stops. My mind starts recalibrating and evaluating all the suffering I have created. I asked myself, “How many more must continue to suffer because of my selfish and impulsive decisions?” My body and its entire existence trembles as I am overcome with remorse. I recall the sorrows of others during my murder trial. All their pain that was expressed before my very eyes and ears. I close my eyes to sit with all that suffering. An endless stream of water flows from my eyes as I drown myself in the pain of those I have hurt.

A mother who lost her son cries out in pain. The sound of her voice still vibrates within me as I sit here. One by one, those I hurt take center stage and express their pain. In that moment I see myself in the courtroom hanging my head down, filled with guilt and shame. I can still hear the words of those I hurt as their pain and sorrow lingers in my mind. I am aware of what is alive in me and I try to connect with the needs of those I have hurt. With a deep intake of breath, I feel the cold air enter my nostril gates as I take in all the suffering. A long extended exhale follows as compassion radiates for all those whom I have hurt, including myself. This was part of the healing process for me and, although there was a tremendous amount of distress, it was a process that I needed.

As I finish writing my story I feel completely depleted. A sense of relief is draped over my relaxed shoulders. All the reluctance and fear of writing about my childhood or harm I’ve caused others is being resolved. I feel an openness and sense of renewed strength in being vulnerable. The guilt and shame I felt in regards to dishonoring my family by writing is exiled. This journey of writing was a rollercoaster for me. I was finally letting go of all the suffering I held inside. I found a peaceful acceptance of my past. The web connecting my past with the strategies I chose in life to meet my needs were all prevalent. All of my pain was displayed on those sheets of paper. I knew at that moment that my next task would be to share my story with someone who supported my new lifestyle.

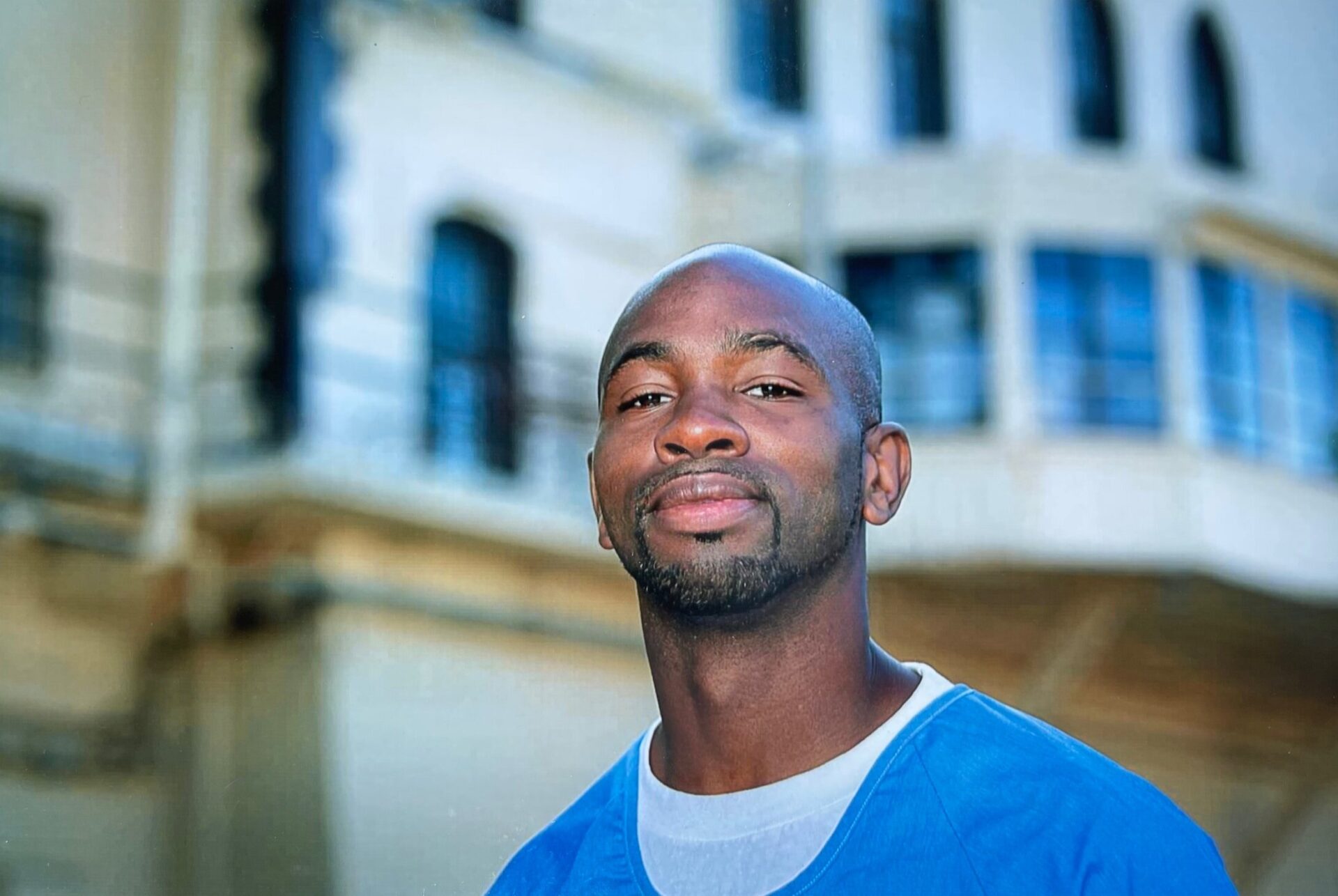

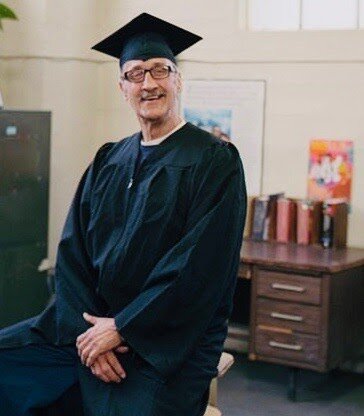

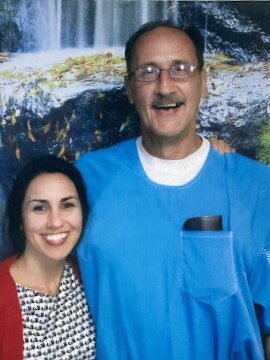

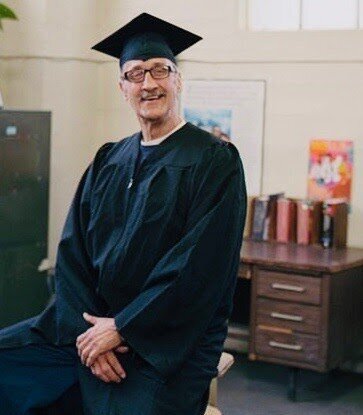

Who would have thought I would find the support I needed within these prison walls. In 2015, I was convicted of second degree murder. At that moment I thought I had lost everything and would spend the rest of my life in prison. The feeling of hopelessness was adamant concerning the prospect of perpetual imprisonment. To diminish that feeling I sought help from others who could show me how to change my distorted thinking. Looking back, prison has helped me change into a better person. I did not lose everything as I imagined, but gained more than I could have ever dreamed of. Sure, there were difficult times where I thought it would not be able to come out of it, but time and again these instances have proven themselves to be an opportunity for growth. As the layers used to disguise myself fall away, I begin connecting even more with my true self. The process of change was slow and arduous, but with faith I persevered. I saw who I really was and no longer live that double life. Day by day the dark side of me fades away as I embrace that inner child with love. I found happiness within myself and I steer clear of the egocentric lifestyle.

There was clarity in my life and understanding of the interconnectivity of all things. With such insight into my own life I no longer shunned that scared child from within. He was a part of me and we would work together. This allowed me to express myself in a healthy manner. In doing so, I received positive feedback from my peers. The fear of speaking up for myself became a distant memory. The child without a voice was now given one. I felt powerful and courageous in being vulnerable. My shift in perception happened gradually with every experience compounding the next. What I told myself and what I now believed in created that shift. Compassionate self-expression gave me the control I had always desired but without harming others. My life was finally changing for the better and in such an unpredictable environment. Surrounded by hardened men and violence, I found peace and support.

At times I can still hear my mother’s voice, telling me how failure was not an option. She ingrained in me that success and a purposeful life meant making a lot of money and having status. Everyone I grew up with thought the same for me, so I thought. I felt the pressure to be something I didn’t even know how to be. Recognizing the pain and suffering that this ideal brought me, I had to let it go. I have never not given up on my dreams, but they have changed. Success and purpose to me is no longer equated with monetary value or status. Failure to me was now an opportunity to adventure beyond what I knew and to explore regions of the unknown. After years of contemplation and meditation there was clarity for me. I asked myself, “What is more purposeful in life than making connections with others?,” “Could it be that the younger me from years ago was simply lacking connection?” The more I dove deeper into my own self the more answers revealed themselves. My lack of empathy, compassion, security, peace and balance had led to a tornado of feelings twisting inside me that expressed itself with destruction on the outside.

Living that double life was a delusion in which I myself created in hopes of achieving my parents dreams and to reside in my own desire of pleasure. All that was short-lived because it was a mask to cover up the pain. As the spiral of feelings erupted inside of me, that double life came crashing down. My life history and lifestyle foreshadowed what was to come in the future, but I refused to look at my own problems. Entrenched in my own denial I saw the world in a shaded veil. Prison allotted me the time and freedom to look at what I had avoided. My past was no longer a mystery, as the process of exposure was under way. Recognizing my denial and coming to peaceful acceptance of all the suffering I have experienced and created was the journey that shed light on my dark side.

I am finally ready to share these sheets of paper. I know it is the next step in progress for me. I share my experiences and insights with a group of fourteen. This proved to heighten my own sense of wellbeing and was an inspiration to others. Over time the people who heard my story multiplied in numbers as I became more confident in speaking about my life. My story helps create new connections with people and offers understanding to myself and those I have harmed. In every instance that I share my story I end with a quote that has a great impact on my life, “There is only one thing permanent in life, and that is change.” What a fickle thing life is. Pain and joy has become interdependent to me as I view the world through new lenses.