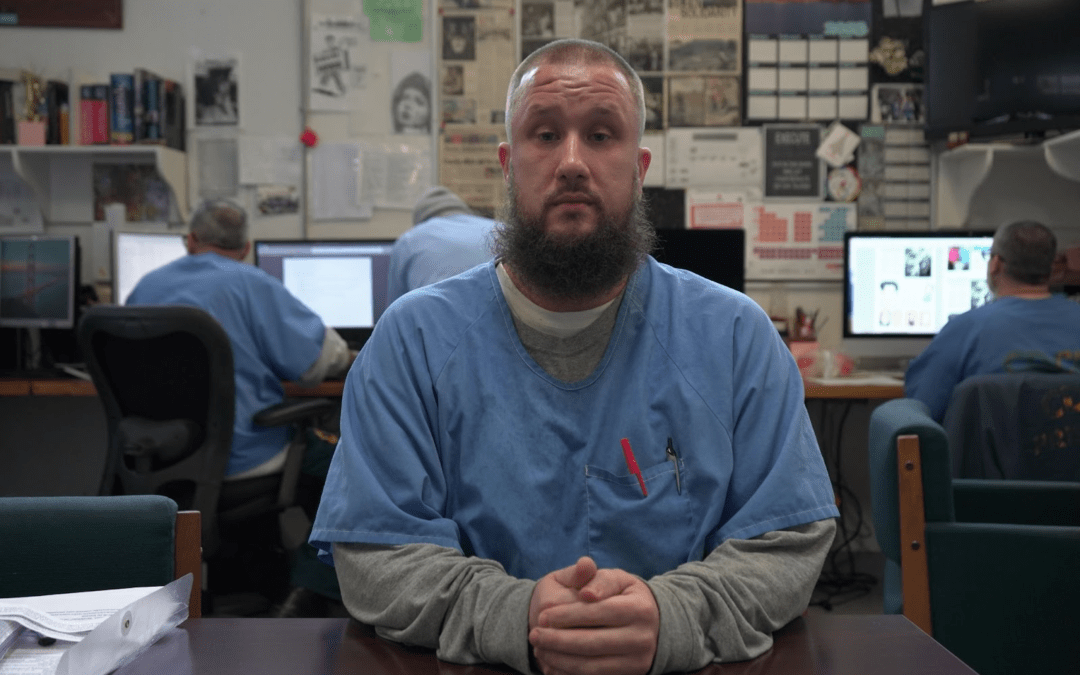

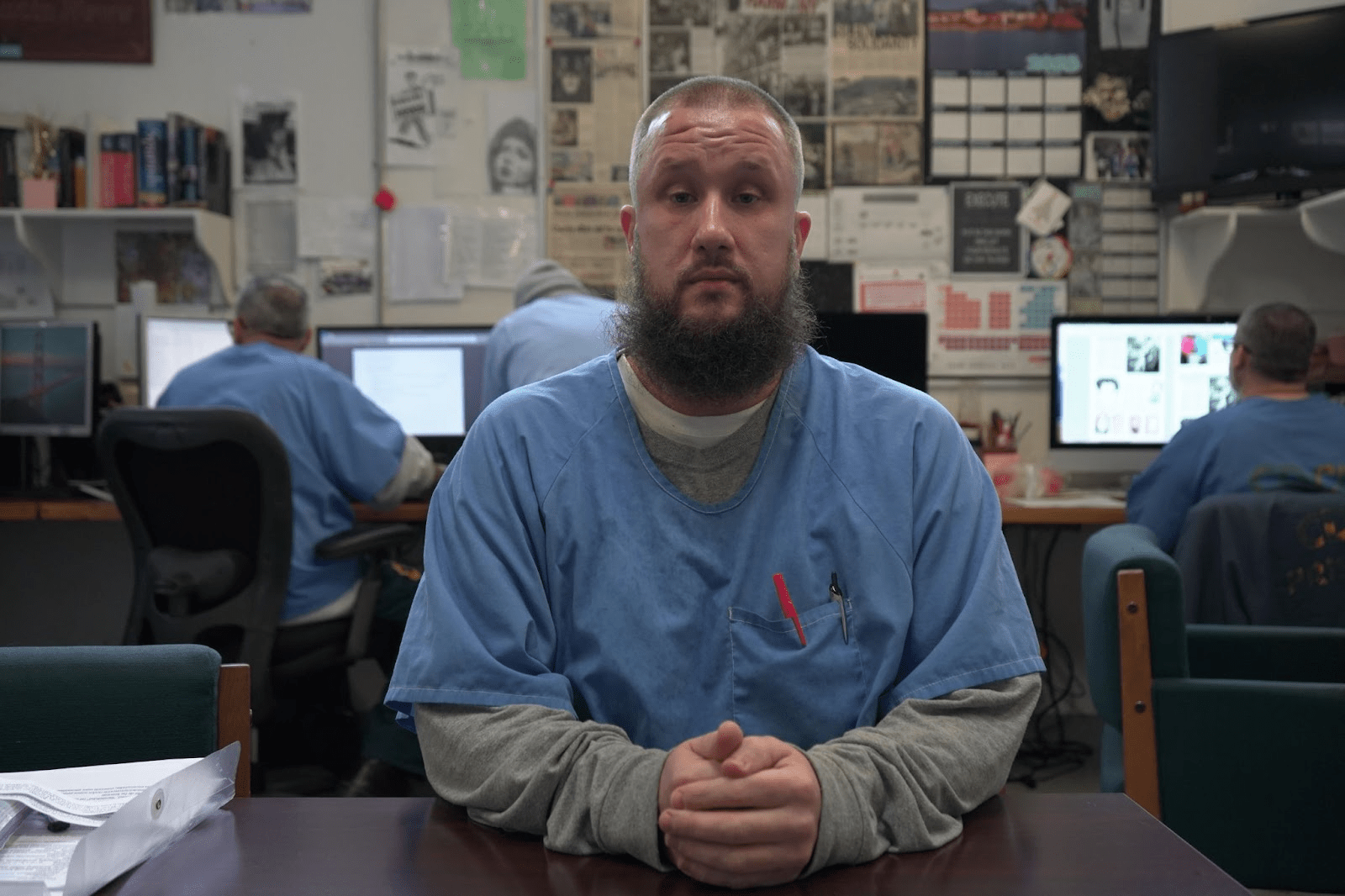

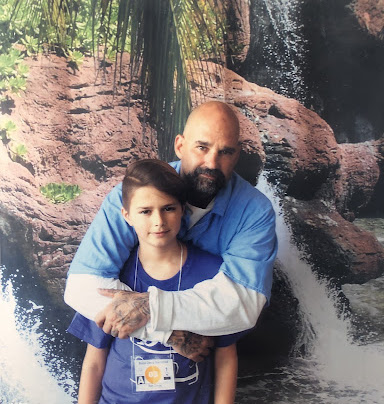

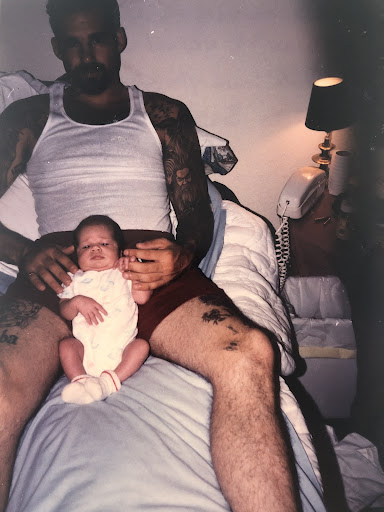

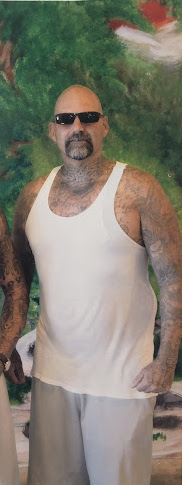

I’ve been in prison for nearly 35 of my 62 years on earth. Though I certainly regretted my role in the crime that took an innocent life, remorse didn’t fully begin to develop until I lost two of my own family members to gun violence in 2008.

Another significant factor in my overall rehabilitation came in 2015 when I was invited to paint murals at Avenal State Prison. I felt like I was doing what I was born to do. Painting became so therapeutic for me that I was moved to co-found a self-sustaining art group a year later in order to offer other inmates the opportunity to realize the same benefits I derived through this creative outlet.

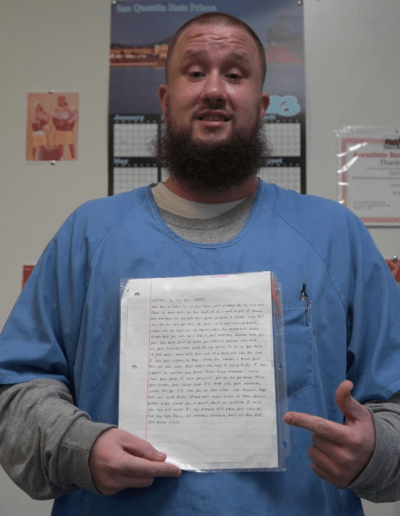

Aspiring to produce more expressive works, my submissions to Humans of San Quentin depart somewhat from the photorealism I generally aim for. The abstract paintings “Peccani” and “Nil Desperandum” are expressions of contrition and hope, respectively. Nearly a decade ago I read an article about an abstractionist from the 1980s who found inspiration for his masterpieces by squeezing his eyes shut and observing the images captured there. Years later as I contemplated the impact of my crime while staring into middle space across the dayroom, I closed my eyes tightly against the tears that threatened there. The bright overhead lights and sunlight spilling in from the high windows burned their impressions into the dark red field of my eyelids. Influenced by this unorthodox technique, as well as “Light Red Over Dark Red” by Mark Rotuko, “Peccari” is both an abstraction of prison and an acknowledgment of my crime.

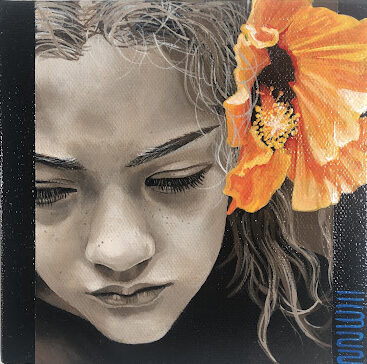

“Nil Desperandum” is not as solemn in its imagery or color scheme, but it lacks no depth in mood. Its inspiration came from a photograph by a well known Bay Area photographer, Amy Ho. About six years ago while flipping through pages of a photography magazine, I came across an ad for an art exhibit in San Francisco. A picture of “Wall Space II” was featured in the ad, and though it was no more than an inch in size, I was instantly captivated by the warm-toned image. It possessed for me both mystery and promise. Although my interpretation of Amy’s stunning photograph is rendered in cooler colors for a more ethereal effect, I hope it does not deviate too far from the emotions evoked in the original.

When did you start painting?

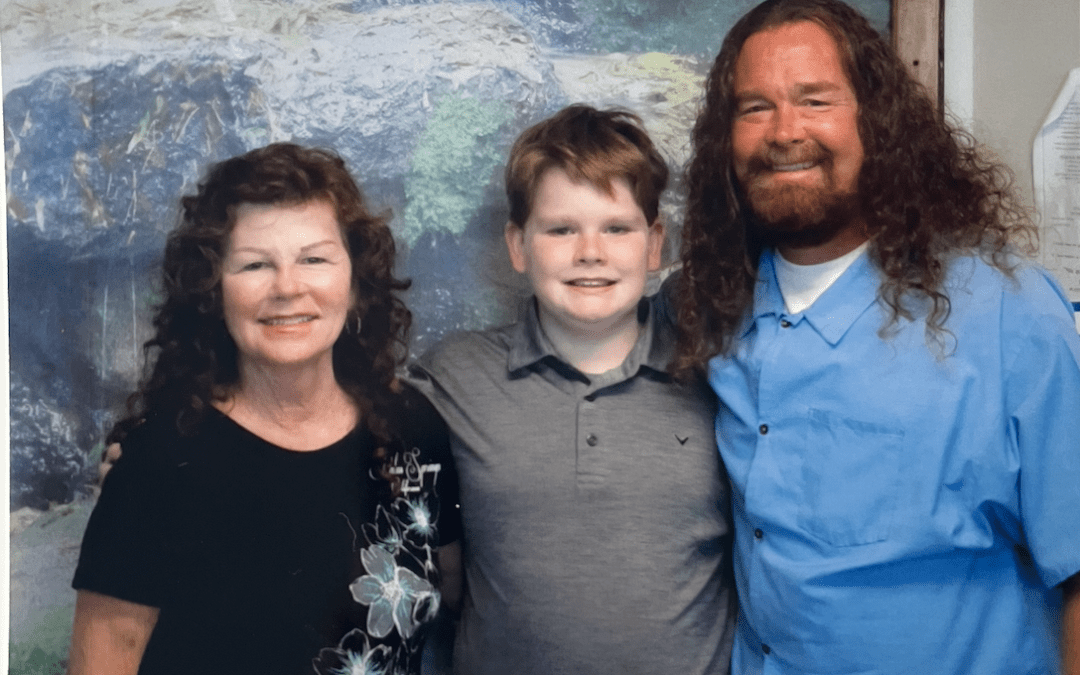

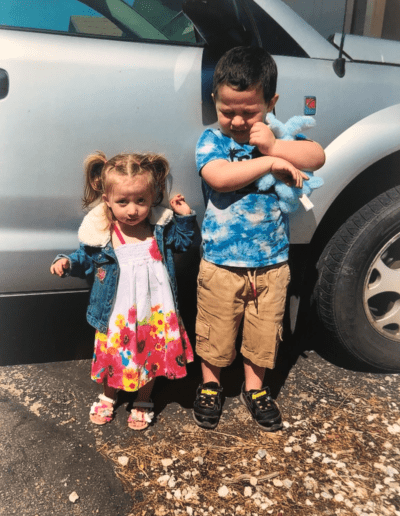

Evidently, I’ve been drawing since before I can remember. Literally. For far too long I had thought that my twin brother, William, and I started drawing when we were about five or six years old. This mistaken belief was dispelled when my mom came to visit in 2016. The conversation turned to a mural I had painted. My mom reached for my hand and told me an adorable story of when William and I were two and three years old. Our dad had taken her out for the evening, leaving us and our younger sister, Sheri, with the babysitter. When my mom and dad returned, the sitter met them in tears. Panicked, she pleaded, “I was with the baby, so I didn’t know what they were doing in there.” Instantly alarmed, my mom pressed the girl for answers. “You’ve got to see this for yourself,” as she led the way to our room. When she opened the door, my mom’s jaw dropped. William and I had used our crayons to draw on the walls of our bedroom. She said,”There were planes taxiing, taking off, in flight, and landing in a colorful panorama that spanned two of the walls your dad had painted earlier that day.” The cuteness of that story notwithstanding, I grew up in a dysfunctional household. Drawing became a means to escape the violence and neglect. I continued to draw throughout my life, but I felt like my work lacked emotion. I had been searching for years to find an outlet to express myself in more meaningful ways. Seven years ago, I was given the opportunity to paint murals. Although I had never painted before, I possessed an unflappable belief that I could. My very first painting was a 17’ x 81’ wide mural. It was so well received that other painting opportunities arose immediately. I began to notice self-confidence had gotten a bit of a boost from the adulation too. Coming from a broken home in disadvantaged neighborhoods, I had long struggled with low self-esteem and worthlessness. When I began to realize how transformative art had been for me, I co-founded Artistic Rehabilitative Therapy (ART), a group designed to offer incarcerated individuals the rehabilitative benefits I derived from painting. That’s when I really became mindful about what I painted. I wanted my work to represent where I am in my recovery. ART was so successful that we became self-sufficient in short order. With the invaluable support of Warden Ndoh and Dr. Hughes from Fresno State University’s criminology department, we became involved in community projects, had our work exhibited at their graduate gallery and at a year-long installation at Alcatraz Island. We also received local television news coverage. All of these accomplishments were character-building experiences for the men involved, and a reminder to me why painting is so important.

What is art to you?

A nineteenth century American painter once observed that the purpose of art is not to teach, but to evoke an emotion. I hope the works that I present to the world today evoke emotions and express who I am today. It is liberating to be seen in my authenticity.

What made you want to share your work with Humans of San Quentin?

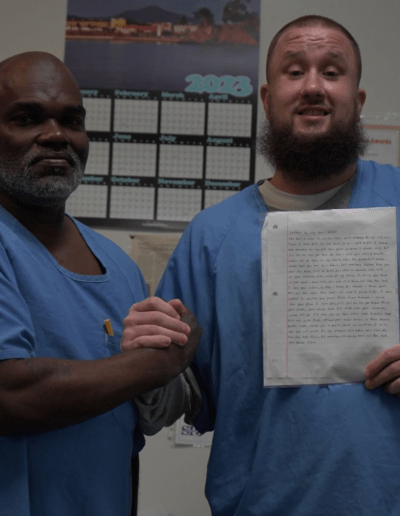

My answer is three-fold. First, I am pro-socially driven. Donating my artwork to worthy causes in the past have been rewarding experiences for me. I fully embrace the HoSQ ethos and was moved to offer what I could in support of their cause. Second, I have learned that the need to paint is an integral part of my rehabilitation. It helps me stay balanced and to express things that are too big for words. Like, remorse, for instance. Each of the paintings I submitted to HoSQ was accompanied by a brief explanation of the emotion that drives the piece, as well as its inspiration. But my motivation reaches further still. Recently, I was inspired by Zhenga Gershman, a Los Angeles-based artist who started a movement called “Brushes Over Bullets.” She paints portraits of people affected by war. Her current series features victims of Putin’s war in Ukraine. I was literally moved to tears by one of her paintings. It depicted a little girl crying and was aptly titled “Tears.” Notwithstanding my concern for the innocent lives lost and those who remain in peril from Russian aggression, the image of that little girl could have easily been culled from news stock of a child grieving the loss of a parent, sibling, or friend to gun violence in any American city. Gershman said she wants her viewers “to feel so much empathy that they’d rise up and do something.” She succeeded. I hope to emulate her movement in slightly different terms. I strongly believe a movement, perhaps “Canvases Over Crime,” depicting people impacted by crime, could dovetail into the victim impact pathos currently taught to offenders in prisons nationwide. I envision evoking empathy with indelible images that compel others to action, just as Gershman’s paintings moved me. If incarcerated people painted the images, they could develop empathy through the creative process. The idea is still in its embryonic stage, but I hope by sharing it on a social media platform through HoSQ, I may attract collaborators to help me see it through. Third, I have a voice of reformation that I believe can be heard through the HOSQ venue.”