Growing up, the two primary male role models in my life were my father and stepdad. Ultimately, from these two men I learned what it meant to be a man. My father was always a good financial provider; however, he was also an abusive alcoholic. His neglectful and abusive lifestyle led to my mother divorcing him. Thus, since the age of four, I grew up in a broken home. This may seem normal to some people, but to me as a young child, it did not feel normal.

My mother immediately entered into another neglectful and abusive relationship with a man who became my stepdad. Unlike my father he was rarely physically abusive to my mother, nor was he an alcoholic. However, the emotional abuse that he subjected my mother and us boys too hurt just as deeply. For reasons that I’m unsure of he had dropped out of school in the eight grade and became addicted to various drugs. His idea of communication was, “because I told you so” and “go outside.” For several years following the separation from my family, I felt confused as to why my father and older siblings (five in all), and especially my sister Tammy who is eleven years older than me, never came to visit me. I felt lonely, and abandoned, but over time I learned to pretend those feelings didn’t bother me.

Throughout those years we moved several times, and were regularly on welfare. My mother worked on and off, but my stepdad seldom worked. This left him a lot of time to lie on the couch, watch television, and yell at my mother, me, and my younger brother. I remember that when I was about the age of nine, I told myself that I would never become like my parents.

At the age of thirteen, I learned that my mother and stepdad had been using drugs throughout the years. This made me feel disappointed and resentful because I believed they chose to spend their money and time on drugs rather than on me and my younger brother. It was then that I promised myself that when I grew up, I would never use alcohol or other drugs.

By this time in my life I had suppressed a lot of anger. So when my mother and stepdad demanded that I begin to stand up for myself and younger brother to protect us from being bullied, I began fighting at school. At first I was afraid, but afterwards, I noticed it felt good to let out some of my hurt and pain onto others. My parents who seldom communicated with me, and who were, for the most part, uninvolved in my life, began to praise me for standing up for myself. Their praise felt comforting, and needing more of their acceptance and attention, I continued fighting.

At the age of sixteen I moved from Red Bluff to Yuba City to live with my father who remained single and lived alone. I believed by moving in with him that I would have a better quality of life by providing me with the emotional and financial support, and encouragement that I needed and wanted. At first, life was great. My father encouraged me to earn good grades and to participate in sports. Wanting to make him proud, that’s what I did. However, within the first couple of months my father slipped back out of my life and back into his lifestyle of addiction which consisted of working during the day, and drinking alcohol in the evenings. Consequently, he became uninvolved in my life which left me feeling rejected and lonely. Being the new kid in school, coupled with the loneliness and rejection I felt at home, I decided to attend my first teenage party. The acceptance I felt was a powerful motivator for a teenage boy.

At the age of seventeen, I began using alcohol, marijuana, and methamphetamine on a regular basis. Though I did not know it then, it was providing me an escape from the emotional pain I had harbored for years.

My addiction to meth soon consumed my life. I used it everyday for the next five months. I went from earning a 3.8 GPA the first semester of my junior year, to dropping out of school the following semester. My father then kicked me out of his house and sent me back to live with my mother and stepdad. I did not realize it then, but I was becoming the man whom I had promised my younger self I would never become.

Within the following year and a half, I had been arrested a number of times, including two DUI’s, assault and battery, and brandishing a firearm. I was eventually sentenced to six months in jail. Up until then, those were the longest days of my life. While incarcerated I told myself that I would never again be locked up.

Prior to my being sentenced to six months in jail, I met two young men, Mike and William who became my best friends. I also met a young lady, Shauna whom I soon fell in love with, and we began to date. With Shauna in my life I felt loved and accepted which provided me with the sense of belonging that I had not felt since I was a young child. For the next seven years all of us spend nearly every celebration and holiday together.

Within the first year of Shauna’s and my relationship, I began to neglect and abuse her. It began with ignoring her and calling her hurtful names. Afterwards, I would feel convicted and ashamed, so I would apologize, promising that I would never speak to her like that again. In my mind I attempted to justify my behavior by telling myself, “at least I don’t hit her like dad and pops (stepdad) use to hit mom.” However, I never truly intended to change. As time passed, though, I eventually became like my fathers. I began to physically abuse Shauna. I attempted to justify this abuse by being a financial provider, and minimizing my actions by saying to myself, “it’s not that bad.” But deep down inside I knew I was wrong. I attempted to hide from the shame I was feeling by consuming larger quantities of alcohol and maijuana.

The cycle of domestic violence that I witnessed in my family throughout my childhood and adolescent years, I was now inflicting on the woman I loved. The years of neglect and abuse that I harmed Shauna with caused her to develop deep emotional resentments, insecurities, and shame that ultimately pushed her out of my life. After seven long-abusive years, she ended our relationship which caused me to feel devastatingly heartbroken. Two days later my father passed away. I attempted to escape the compounded feelings of grief and loss by increasing my consumption of alcohol and marijuana. During that time, in my mind I thought, “I’m going to end up just like my father,” who, following the separation of my mother, lived the remaining twenty-two years of his life a lonely alcoholic.

Shortly afterwards I learned that one of my best friends from the previous eight years, William, was dating Shauna. Over the following two weeks my internal dialogue of negative self-talk, and self-doubt, kept me from taking responsibility for the years of domestic violence I had subjected Shauna too, and in doing so I had no right to decide who she could date. This way of thinking also kept me from reaching out for help, finding closure, and walking away and starting my life anew elsewhere.

Grieving the loss of my relationships of Shauna, William, and my father, I was depleted and left with obsessive thoughts of jealousy, loneliness, betrayal, shame, and hopelessness. I misled and deceived myself into believing that I needed to “stand up for myself”, and I was entitled and needed to get revenge. I committed the worst crime imaginable. I murdered two innocent, kind human beings, William who was only 29, and Shauna who was only 24. Never once during those times did I ever stop to consider how many lives I would painfully affect and impact through my selfish and cowardly actions.

Becoming The Man I Never Thought I’d Become

Part Two

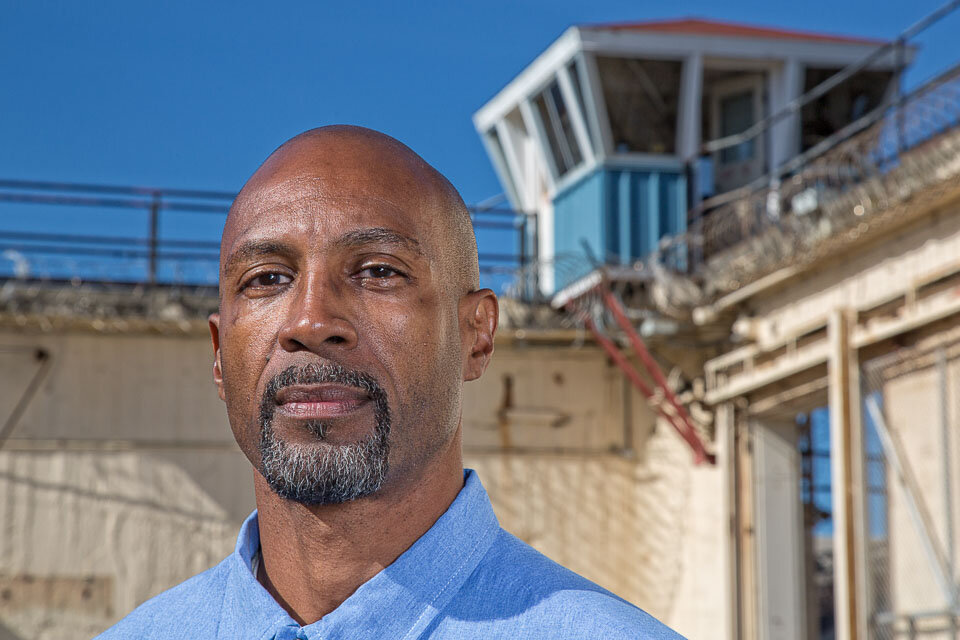

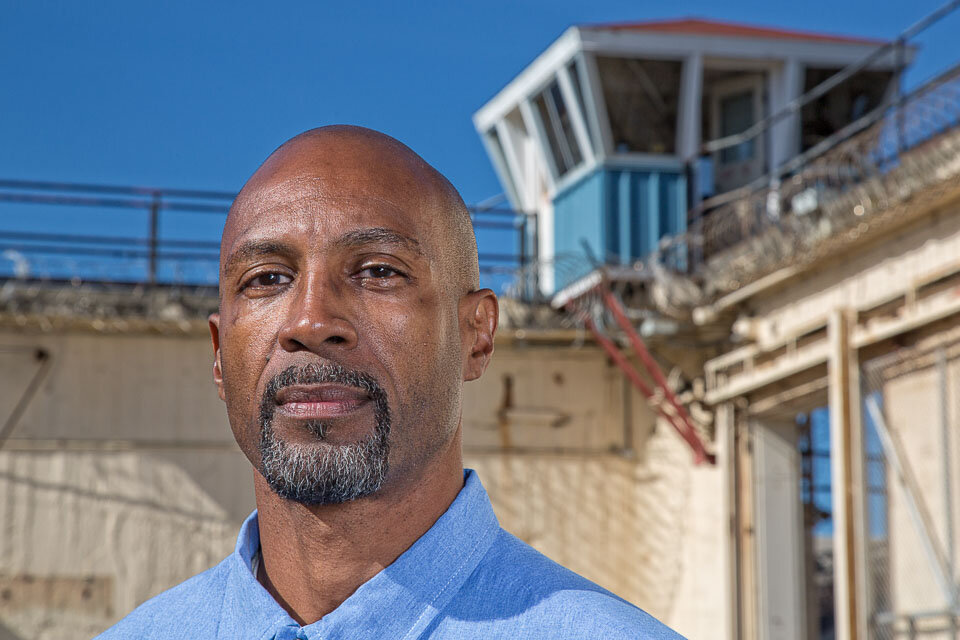

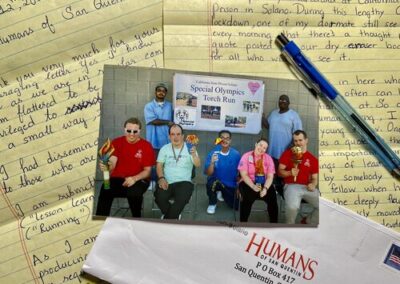

Arriving at prison seventeen months later with a thirty-four years to life sentence, I felt hopeless, depressed, and completely out of place, the place I told my younger self that I’d never again be locked up. I thought about suicide, because I could not imagine living the rest of my life in prison. My first year in prison (1999) all I could think about was myself, my troubles, my fears including how I was going to survive. At that time I was housed at Pelican Bay in which riots and killings were “normal.” The prison atmosphere was new to me, but not the violent life, although that too was different.

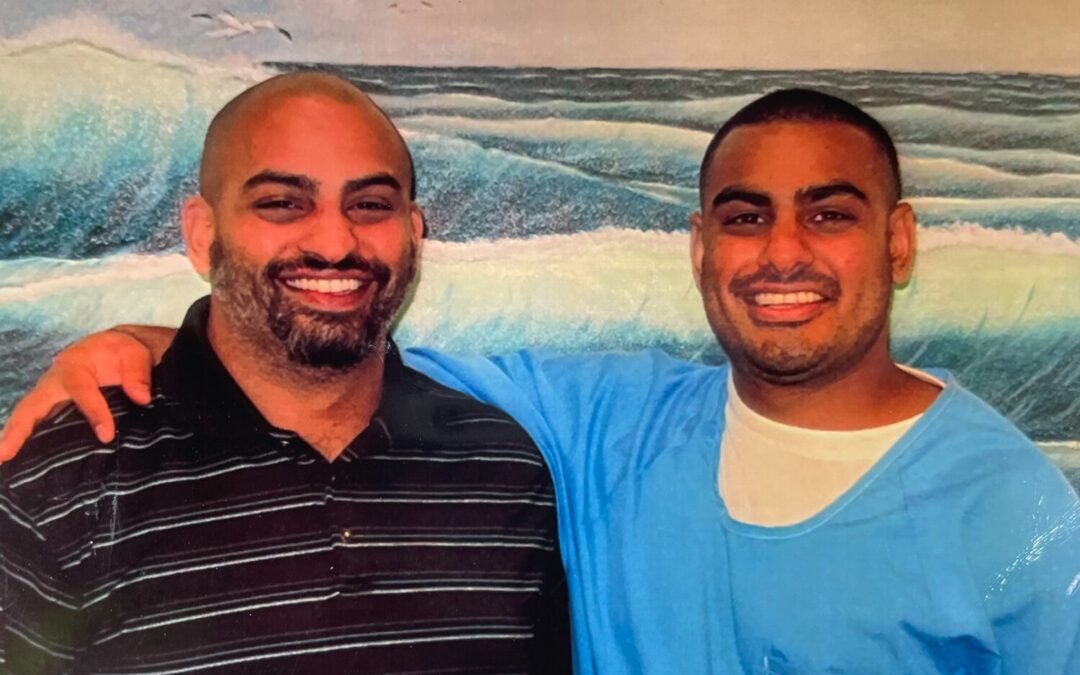

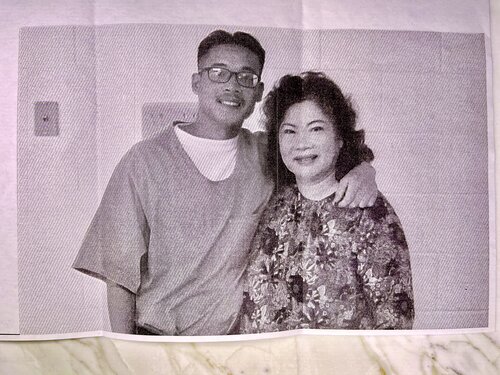

My mother, sister Tammy, and brother William were the first to visit me. During those visits, I remember watching them cry each time they would visit me. I knew they missed me, but I didn’t understand why they cried.