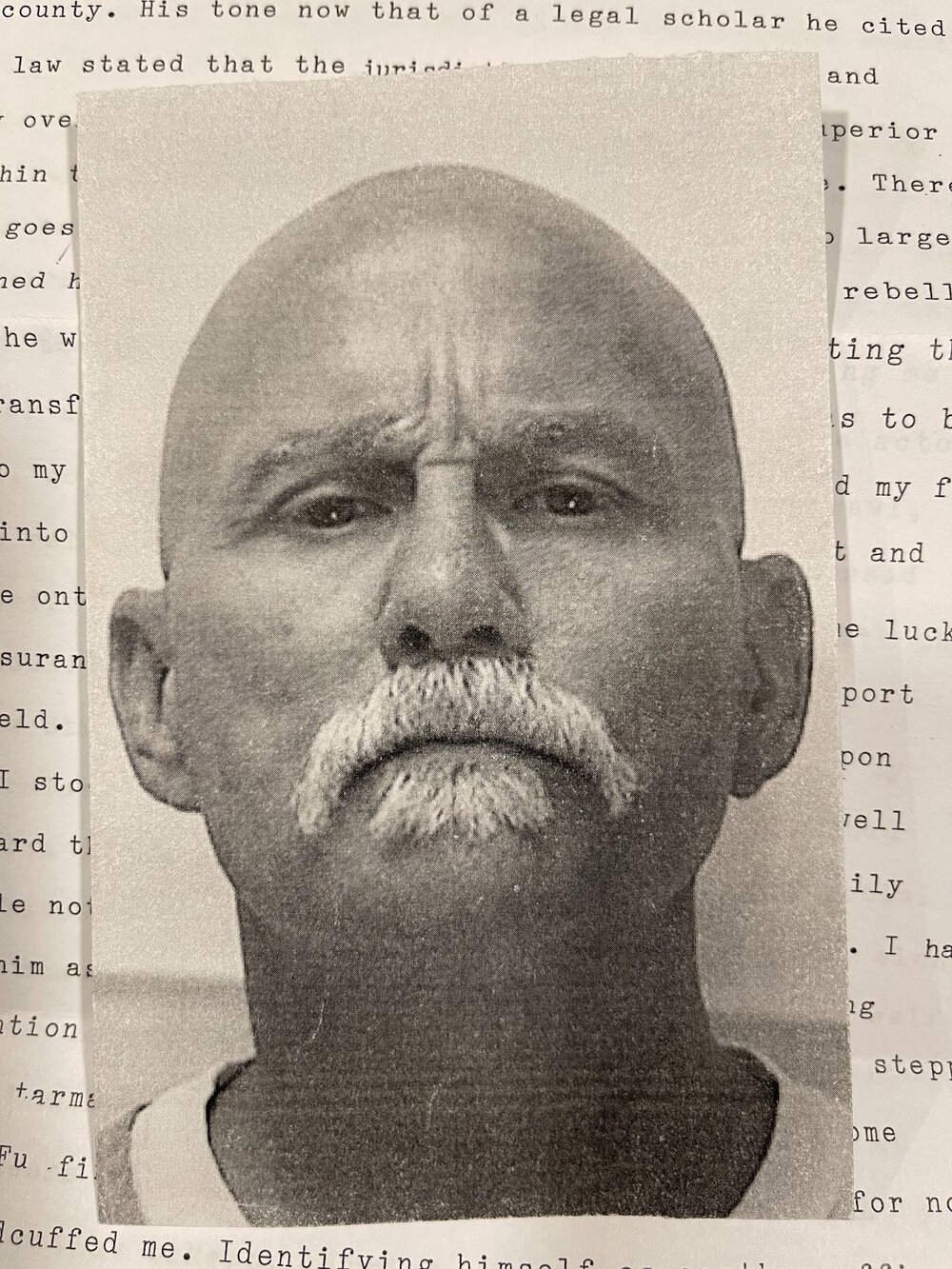

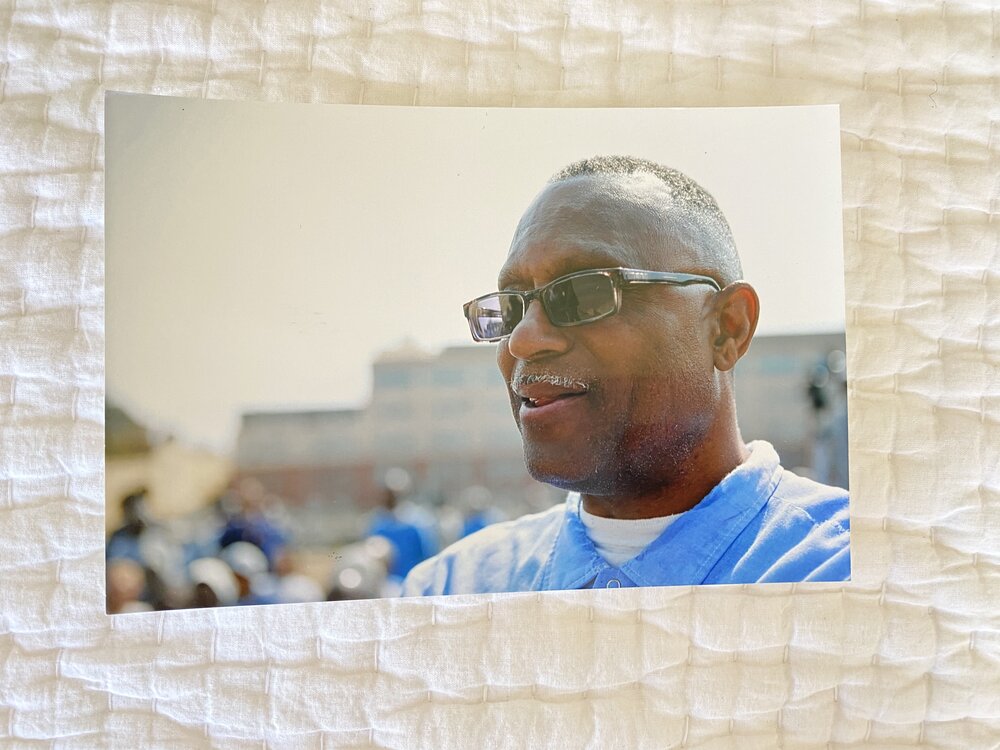

Scott, 61

Meet Scott

The first time I was locked up, I was six. The state had taken me from my mother and made me a ward of the court. Over the following years that first cell would be the state’s repetitive choice of places to deposit me in the interim periods between multiple foster homes and boys ranches. I was thought obstinate and accumulated an angry fistful of failed placements.

For seven years the state clutched me to it’s sour bosom and raised me with it’s judicial parenting skills.

Change came with no notice in the form of a fidgety officer who appeared unexpectedly at the boys ranch. He informed me that there had been a change in my legal status instigated by my mother’s action to relocate to another county.

The law wanted jurisdiction over my case and authority over my physical custody, which meant it resided with the superior court in the county of my mother’s legal residence. Where she goes, I must go.

He waved papers in the air between us, stating that he had a transfer order and I was going with him. I was to be returned to my mother. Ten minutes later, having packed my few belongings into a duffle bag, he drove me to the airport and escorted me onto a plane.

He shook my hand and wished me luck with the assurance that someone would meet me at the airport in Bakersfield. I assumed I would be met by my mother. Upon arrival, as I stood at the top of the truck mounted stairwell looking toward the terminal building searching for my family, I gave a little note to the man at the bottom of the stairs.

I had identified him as some sort of airline employee and was paying him no attention as I reached the bottom of the stairs and stepped off the tarmac.

Simultaneously snatching my hand in some sort of Kung-Fu finger lock, asking my name, but waiting for no answer, he handcuffed me. Identifying himself as another officer of the court, he picked up my discarded duffle, took me by the elbow, and marched me through a small sidegate to a waiting car.

I remember the air was hot and smelled like acrid chemicals. He sped through the city to the detention facility. It would take four months and several court hearings before I was finally released to my mother, but it was in those months of purgatory that I first met Mr. Dalton, who would only later open my gateway to learning.

I was thirteen years old and locked up in a cell when my formative lessons began. He worked the graveyard shift as the cell block turnkey. Our interactions were limited to him unlocking my cell door and escorting me to the pisser and back.

When the state finally released me to return home to my family our relationship was strained and problematic. I had been away from them for so long that connection between us had weakened, or been lost. I had been alone for so long that I had become emotionally emancipated and self dependent.

Not at all tolerant of, or responsive to, supervision or control, I made my own way into the world. With little in common with my peers my own age, I gravitated to a circle of mostly older people; outlaw bikers, hippies, dope fiends, pushers and crooks. Those on the shadowy fringe of society.

I was soon deeply submerged within a hard-core drug culture and shooting speed, coke, and heroin. During this time I would often bump into Mr. Dalton, who was simply Dalton in the free world. I saw him at parties, river and lake outings, concerts and other social gatherings. He also dated a girl I knew well. He was more socially aligned with the hippy-biker element and was not a dope fiend, pusher, dirtbag or crook. Our interactions were kept to a nodding acquaintance in passing and no more.

Again finding myself back in that cell block where he worked, our relationship developed more fully to the point where he would secure the block to insure privacy and unlock my cell door so I could come sit and talk with him.

He was a college student and there was always a stack of books and papers piled around him. One night I picked up a paperback which had a title that caught my attention. It was Thomas Wolfe’s “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test”. Intrigued, I asked if I could check it out. He tore the cover and title page off and told me I could have it.

Before that book I remember no school lessons lodging in my mind. My reading experience was limited to underground comics, and the stacks of torn up conventional comics scattered about the cell block. That book was different, and I devoured it.

Dalton saw it had touched me and seeing I was hungry for more he began feeding that need. He brought me books as fast as I could read them. Books and authors such as Ken Kesey’s “Sometimes A Great Notion” and “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest”, Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22”, Darton Trombo’s “Johnny Got His Gun”, Robert E. Persig’s “Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance”, Ernesto “Che Guevara’s “The Motorcycle Diaries”, Aleksander Solzhenistsen’s “The Gulag Archipelago” and “One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich”, Upton Sinclair, Hunter Thompson, John Irving, Kurt Vonnegut, and many more.

These authors filled the loneliness of my cell, painting the stained graffiti covered walls with their vivid language through them, and began to develop my own voice in writing which would continue to grow by necessity and become invaluable over the more than thirty years I would spend in prison cages.

Prison is by definition a thing meant to isolate a man from the world. Letters are the only avenue to communicate with the people outside the walls. No one wants to receive the same old dreary letter. It became essential that I learn to communicate through writing in a more expressive way, to both entertain and explain myself. Reaching out from a cage, I had to broaden my writing abilities in order to touch them. Those language skills would allow me to define myself to them and often dispel and change preconceived notions about who I am as a person.

The pathway to my acquiring and learning language opened up my ability to communicate and improved my efforts to remain connected to the real world from the purposely imposed social blindness of prison.

My life and all my dreams have been nurtured by language and literature. It has been a tether to reality within this unreal world of cages.

Backstory

Describe yourself to an unsympathetic audience

My life was warped in childhood by a lot of weighty negative burdens. Now, I know those things slowly but solidly forged a chain that shackled me as a boy to the man I would become. That chain would drag me inescapably to a future holding nothing good.

The links of that chain were forged by my father’s abandonment of his wife and seven children condemning us to struggle in poverty.

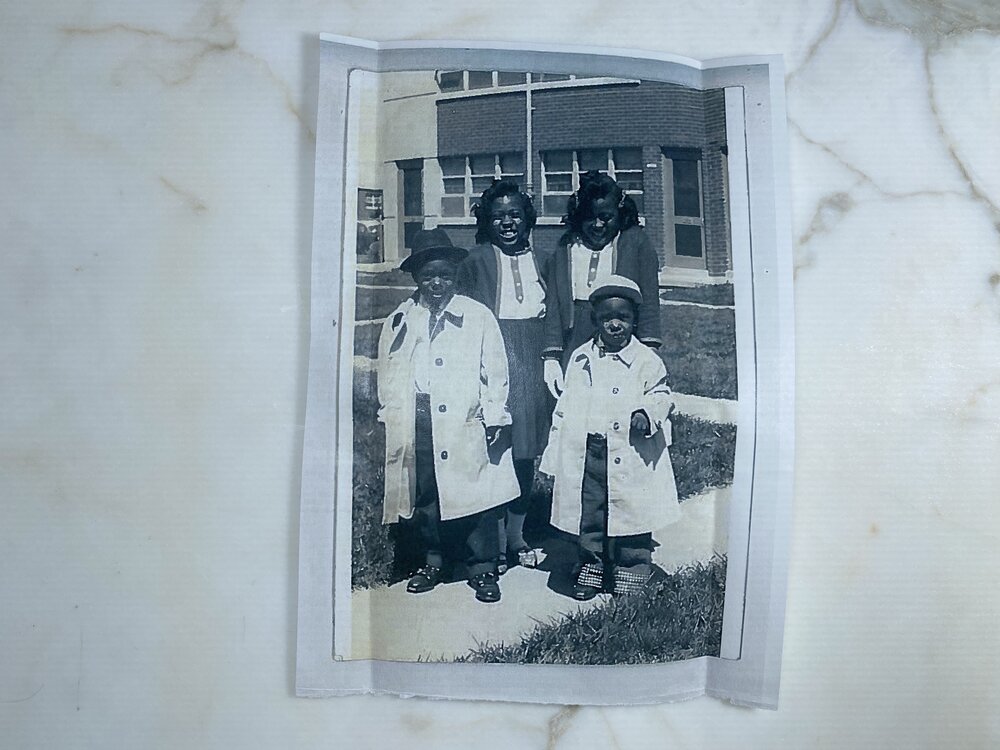

My mothers long hours at work allowed supervision and guidance to badly deteriorate tasks for us as a group. We behaved badly. I, the youngest, tagged along behind and in the company of three older brothers and by example and participation learned a warped way of criminal thinking and lost any sense of guilt or shame, as well as any fear of consequence.

We became crooks together. The level of our crimes grew more serious with every lesson. We were thieves. Shoplifting all the things any kid could want, from candy to sporting goods. We were prolific burglars, both for theft and fun. We vandalized property at enormous destructive costs to all. Plundered businesses. Broke into vending machines and telephones too many to count. Our crimes reached felonious levels of severity that no civil community can ignore or tolerate.

At age six the state took me from my family and I became a ward of the court. It was my first experience of being locked in a concrete and steel cell.

From age six to fourteen, I endured several failed foster home placements. Two court commitments to “Boys Ranches” that had nothing to do with ranching. Between each, in the interim periods I was returned repeatedly to those cells in detention.

At fourteen I was returned to my family. In all those years of our separation I had suffered no improvements from the state’s judicial parenting skills. I felt alienated and a stranger to my family. Emotionally emancipated, stubborn with a twisted mindset and world view. Uncontrollable and unguided.

By fifteen I was strung out on heroin and speed and used all the crooked skills and not very well. Repeated recidivism that predictably led to prison for several terms that cost me more than thirty years of life and which is still tolling.

That’s the man people see.

Admittedly, from any angle grounded in normal decent social moral values, and even from my own viewpoint, it would be difficult not to know that I am an asshole. From my own actions and deeds a proven damn unteachable fool.